I took my iPhone out of my backpack, in the hope that I might deal with some of the shit heaping up at my door. An email I’d been composing for Hugh McIlvanney about João Zarco looked unimprovable, so I sent that, with a copy to Sarah Crompton. Jane Byrne wanted to stage a reconstruction of Zarco’s last moments with the help of Crimewatch , at our next weekend home fixture. I said yes to that. Another one from UKAD invited me to a meeting at the FA head office so that my memory could be refreshed regarding drug-testing protocols. Stupid sods. Could I do an interview with Football Focus ? Fuck off; I’d already said no to Gillette Soccer Saturday and TalkSPORT. I had an old mate from Southampton who’d been given the manager’s job at Hibs and did I have any advice for him? Knowing Edinburgh, I did: don’t let the bastards get you down.

Then I scrolled through some texts: the Rape Crisis people wanted a donation, to which I said yes, and Tiffany Drennan informed me that Drenno’s funeral would be on Friday, to which I also said yes. Viktor had sent me a text saying he would be back from Russia in time for the match on Tuesday night, and that Bekim Develi would be coming with him; and the red devil himself had sent me a text in which he told me he was looking forward to playing for City and felt sure that ours would be a very successful relationship. I texted him back a one word ‘Welcome’. Meanwhile, on my iPad, I quickly Googled Warwick Square and discovered that it had its own website, with an active residents’ association and a useful table of property prices. Flats were a staggering two million quid, while what few houses there were for sale started at a cool eight million.

It never surprises you what your own house is worth, but it always surprises you the price that other people want for their houses.

‘Can I help you?’

The man looking at me was thirtyish, thin, and about six feet tall; he wore a brown Crombie coat with a velvet collar and a yellow hard hat.

‘I’m a friend of Zarco,’ I said.

‘Yes, I know,’ he said. ‘I’ve seen you on the telly, haven’t I? On A Question of Sport .’

‘You’ve got a good memory. Is there somewhere we can talk?’

‘What about?’

‘I understand you went to see Mrs Zarco,’ I said. ‘About some money you say you’re owed. Twenty thousand quid, to be exact.’

Tristram Lambton hesitated.

‘It’s all right,’ I said. ‘You say you recognise me off the telly? Well, that should reassure you I’m not from the Inland Revenue or the Home Office. I don’t care who you’re employing on the site and how you’re paying them. I’m here to help Mrs Zarco, if I can.’

‘There’s my car. Let’s talk there.’

The Bentley was silver grey with all the extras; when you shut the door it sounded like you’d walked through the entrance of a very exclusive gentlemen’s club. It smelled like one, too; all leather and cigars and thick pile carpets.

‘I didn’t know that Mrs Zarco wasn’t aware of my arrangement with her husband,’ said Lambton. ‘I felt really awful about it afterwards. But I thought, widowed or not, the best thing for her now would be to complete the building project as quickly as possible so she can flog the place and get on with her life. Which does seem to be what she wants to do. Frankly the whole job has been a bloody nightmare from start to finish.’

‘That’s certainly the impression I got. But what was your arrangement with Mr Zarco?’

‘The Zarcos have been getting a lot of complaints about the building work from the neighbours. In particular the people at number thirteen, next door — as you can imagine. Which means that I’ve been under a lot of pressure from the Zarcos to get this building finished as soon as possible. And the only way I can get the lads to work the overtime I’m asking them to do in order to make that happen is to pay them double time, in cash. Money really does talk to these boys. That was my arrangement with Mr Zarco. He’d pay the double time himself. The weekends, too. On Saturday he was supposed to stump up the twenty k that would help me to get things finished before the end of March, which is ahead of schedule, I might add. But you know what happened. It’s really too bad. I liked him a lot. Now I’ve no idea what I’ll do. I mean, that’s the end of the double overtime and working on a Sunday.’

‘Not necessarily.’

I’d anticipated this moment. In Toyah’s lavatory I’d separated the bung money into two amounts: twenty grand and thirty grand. The twenty grand was still in the Jiffy bag, the rest was in a compartment in my backpack.

‘Here,’ I said. ‘The twenty grand he was planning to give you.’

‘That’s brilliant. I know it sounds a lot, but these Romanian boys are hard workers and worth every penny. I mean they really do want to bloody work, unlike some of our own. But don’t get me started on that.’ He laughed. ‘Now if you can just sort out Mr and Mrs Van de Merwe at number thirteen, everything will be perfect.’

‘What would you suggest?’

‘Seriously?’

Pimlico is like Belgravia without rich people. The folks in Pimlico aren’t exactly poor, it’s just that much of their wealth is tied up in the value of their flats and houses.

Number twelve was an end-of-terrace property; the house next door was a six-storey white stucco mansion from the early nineteenth century with a fine Doric portico and a black door that was as polished as a guardsman’s boots; or at least it would have been if it hadn’t been covered with a fine layer of builders’ dust. There was a blue plaque on the wall but it was too dark for me to identify the famous person who had once lived there. But I knew the area quite well; Gianluca Vialli had lived around the corner when he’d been player-manager of Chelsea until 2001, and if anyone deserved a blue plaque it was him: the four goals he’d scored against Barnsley were among the best I’d ever seen in the Premier League.

I pulled the old-fashioned doorbell and heard it ring behind the door, but I think I might have heard it ring in Manresa Road.

At least a minute passed and I was about to give up and go away when a light went on in the portico; then I heard several bolts being drawn and a largish key being turned in a probably Victorian lock. The door opened to reveal an old man in a brown corduroy suit. He had a sort of Dutch painter’s beard and moustache that was white but stained with nicotine, and wild grey hair that seemed to be growing in several different directions at once so that it looked like the Maggi Hambling seascape on my wall. On his nose was a pair of half-moon glasses and around his neck was a loosely tied beige silk scarf. He had one of the weariest faces I think I’d ever seen — not so much lined as cracked; you wouldn’t have been surprised to see a face like that shatter into a dozen pieces.

‘Mr Van de Merwe?’

‘Yes?’

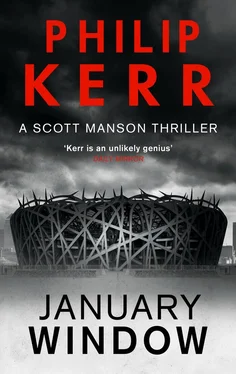

‘Forgive me for interrupting you,’ I said. ‘My name is Scott Manson. I wonder if I might come inside and talk to you for a moment?’

‘About what?’

‘About Mr Zarco.’

‘Who are you? The police?’

‘No,’ I said. ‘Not the police.’

‘Who is it, dear?’ said a voice.

‘Someone about Mr Zarco,’ said Mr Van de Merwe. ‘He says he’s not the police.’

His voice, no less weary than his face, sounded a bit like someone looking for a channel on a shortwave radio. And his accent sounded vaguely South African.

A woman as anxious-looking as a stolen Munch scream came into the hall; she was old and small with a mountain of fairish hair and wore a thick white sweater with a South African flag on a breast that was as large as my backpack.

Читать дальше