Philip Kerr - January Window

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Philip Kerr - January Window» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2014, ISBN: 2014, Издательство: Head of Zeus, Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

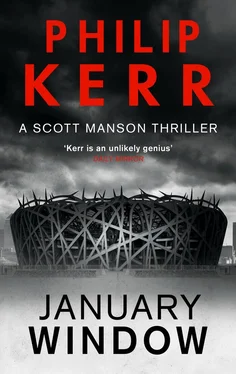

- Название:January Window

- Автор:

- Издательство:Head of Zeus

- Жанр:

- Год:2014

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-1-78408-153-9

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

January Window: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «January Window»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

But this time, it's murder.

Scot Manson: team coach for London City FC and all-round fixer for the lads. Players love him, bosses trust him.

But now the team's manager has been found dead at their home stadium.

Even Scott can't smooth over murder... but can he catch the killer before he strikes again?

January Window — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «January Window», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I leaned out of the window and stared up at the pale winter sun. It wasn’t the view of Silvertown Dock that made me yawn but the fresh air. From my current vantage point the outer part of the stadium was closer to the inner structure than on the ground floor. I could almost have reached out and touched one of the cross beams. I looked down through the polished plaited steel to the ground, about fifty or sixty feet below the window, and then glanced back at the fifty grand that lay on the worktop. What the hell was I to do with a fifty grand bung? I could hardly give it to the police or keep it myself, as Gentile probably assumed I would do. Of course, strictly speaking it was money paid to Gentile and Zarco that should never have been paid at all, which made it Viktor’s more than anyone’s. It seemed almost pointless to reimburse a man for whom fifty thousand was less than 0.0006 per cent of his total wealth, but it looked as if this was probably what I was going to do.

My phone started to ring. It was Phil Hobday.

‘I believe Viktor promised you sight of an autopsy report,’ he said.

‘Yes. I was wondering if he was serious about that.’

‘Viktor never makes idle threats,’ said Phil.

After what Paolo Gentile had told me that wasn’t exactly what I wanted to hear at this particular moment, and I reflected that the chairman might have chosen his words more carefully.

‘Is this from your source in the Home Office again?’

‘Actually, no. Since March 2012 all forensic work in the UK is contracted out to the private sector.’

‘That doesn’t sound very reassuring.’

‘Maybe not. Anyway, it’s here in my office if you want to come and get it. In fact I wish you would. I’m afraid I opened the envelope before I knew what it was. And now I’m rather wishing I hadn’t.’

‘I’ll be there in five minutes.’

36

While Maurice escorted a grateful Terry Shelley out of Silvertown Dock, I got up and locked the door to my office before making myself a very strong cup of coffee with the Nespresso machine that sat on top of the filing cabinet. If there’d been any brandy around I might have added some of that to my mug instead of milk from the refrigerator. I figured I needed something strong inside me if I really was going to play detective for the whole nine yards, and it was impossible even to imagine catching Zarco’s killer without knowing the exact circumstances of how the man had met his death. I could see no way of avoiding it. Ignoring a text from the Guardian soliciting my opinion on the absence of black goalkeepers in top-class football — why was it, for example, that City had chosen a Scot instead of the ‘equally talented’ Hastings Obasanjo, or Pierre Bozizé? — I settled down to read.

I hadn’t ever seen an autopsy report or had anything to do with one before. In fact, I hadn’t even seen a dead body, unless you count the guy in the next cell at Wandsworth Prison who got a shiv in his neck and died later in hospital. The closest I’d come to seeing an autopsy had been on the telly when the almost infamous German anatomist Gunther von Hagens had dissected a cadaver ‘live’ on Channel Four television; it had been fascinating to see the human musculature in close detail. I was of course especially fascinated to see those more vulnerable parts of the human leg that give all footballers problems from time to time: the anterior cruciate ligaments, the knee cartilage, the hamstrings and the groin. I remember gasping that something as simple as a length of tendon at the back of the knee could be so fucking painful when it tore, and that an Achilles could reduce you to a whimpering puppy when it snapped. For me it was like my teacher at school explaining how the Pythagorean theorem works infallibly; or, in the case of the anterior cruciate ligament, doesn’t. Some of those Creationist bastards in the US who are forever arguing ‘intelligent design’ — I’d like to see them do that while trying to play on to the end of a match with a torn adductor muscle.

But while there had seemed a purpose to the carnage wreaked upon a human body by von Hagens, and a genuine investigative value to his carving up a cadaver like a pig carcass in a butcher’s shop, what I was reading now seemed like something altogether different. The pale, rubbery bodies von Hagens used had hardly appeared to be human at all, more like something from the special effects guys at Pinewood Studios — perhaps because they had been emptied of the one thing that had made them human: life itself. And turning the pages of my friend’s autopsy report felt uncomfortably personal, even transgressive. I hadn’t ever sat in a steam bath with any of von Hagens’ cadavers, or embraced them fondly at Christmas; I hadn’t enjoyed a good dinner with any of them, or joined them in joyous celebrations as our team won a match; I hadn’t known them for most of my life. I hadn’t spoken to them less than seventy-two hours ago. It was a little like the computer guy taking your PC to bits in order to fix it — with all of the inside bits laid improbably open for inspection — except of course that no one was going to fix João Gonzales Zarco now. I suppose the moment when it hit me for the first time that Zarco really was dead and wouldn’t be coming back — that my friend and mentor was gone forever — was when I saw a photograph of him lying on the pathology table with a Y-shaped suture zippered up the front of his pale and naked corpse.

What a waste, I thought; what a waste of a spectacularly talented man.

I tried to ignore the many other colour photographs and to concentrate mostly on the text, which was of course written in cold and scientific legalese. The tone was measured, matter-of-fact, dispassionate, like a medical textbook, with very little use of the past conditional tense and almost nothing supposed. Wounds and injuries were simply described and evaluated in an efficient way that rendered them less extraordinary and perhaps, for the detective at least, easier to deal with.

Had Detective Chief Inspector Jane Byrne attended João Zarco’s autopsy? According to the notes, this had taken place during the course of a single hour the previous afternoon. I didn’t envy her if she had. There were better ways to spend your Sunday than listening to the sound of a sternum being snipped open, or the sight of a human crown being removed with a saw like the top of your boiled egg. Perhaps she was used to it. She certainly looked like she was. You can get used to anything, I suppose. More than likely she’d have freaked out at the sight of a badly broken leg on a football pitch, though; I’d seen more than my fair share of those and I don’t think there’s a more traumatic sight in sport. I’d seen several players faint at the sight of a career-ending leg break. What I was looking at now was bad enough but I owed it to Zarco to steel myself to keep reading. Unfortunately there was no cortisone injection I could give myself in order to carry on turning the pages.

Poor Zarco. The pictures of his body, as found by Phil Hobday and the security guards from the dock, showed a man who looked like he had played ninety minutes in goal with his clothes on. These had been examined first and it had been concluded that the body had been clothed at the time of death; the pathologist had matched his injuries to the blood stains on Zarco’s white Turnbull & Asser shirt, his grey Charvet silk tie, and the beautiful black silk coat from Zegna he’d been wearing on the morning of his death. Two grand, it cost him. But it did not look quite so beautiful now after he had crawled some way along the wet ground and several pigeons had come and crapped on him. The knees of his suit were almost as dirty and I was reminded of the night when we had beaten Arsenal and Zarco had ‘done a Wayne’, celebrating with a massive slide on his knees that took him from the technical area right down to the corner flag. Of Zarco’s lucky club scarf — from a shop called Savile Rogue, it was made of cashmere — there was no sign.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «January Window»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «January Window» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «January Window» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.