I almost gasped. That was typical of Viktor Sokolnikov: making a joke out of a rumour that would have been acutely embarrassing to anyone else. Then again he was in a very good mood about something that wasn’t anything to do with the pitch. His face was tanned and he was wearing an enormous Canada Goose coat that would not have looked out of place worn by Sir Ranulph Fiennes at the South Pole. In spite of the bitter January cold he was smiling broadly.

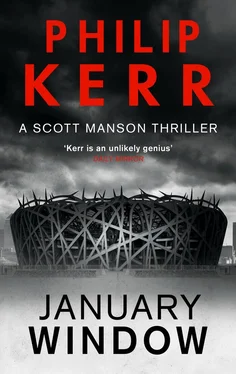

‘Come to think of it,’ he added, ‘I wouldn’t mind being buried here myself. As mausoleums go, I think the Crown of Thorns would be perfect.’

‘Why not?’ said Zarco. ‘You paid for it, Viktor.’

‘But I’d have to do it in secret,’ said Viktor. ‘The local council would never give me planning permission to get buried here. Not without a great deal of arm-twisting. And bribery, of course. You always need that. Even in this country.’

‘We’ll bury you in secret, if that’s what you want. Won’t we, guys? Just like Genghis Khan.’

Colin and I nodded. ‘Sure. Whatever you want, Mr Sokolnikov.’

Viktor chuckled. ‘Hey, take your time there. Reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated. I’m in no hurry to be under the ground. Let’s think about burying Newcastle here tomorrow before it’s my turn.’

‘After the Leeds match?’ said Zarco. ‘We’re unstoppable. Xavier Pepe’s goal was probably the best goal I’ve ever seen in all my years as a manager. And Christoph Bündchen already looks like a star. The team is riding high, right now. Those Newcastle boys will be crapping themselves.’

‘Let’s hope so,’ said Viktor. ‘But we mustn’t be overconfident, eh? We have a saying in Ukraine. The devil always takes back his gifts. I hear that Aaron Abimbole is going to be fit.’

Before signing for Newcastle in the summer, Aaron Abimbole had played for London City, and Manchester United, and AC Milan. In fact he collected clubs like some people collect air miles. The Nigerian was one of the highest-paid players in the Premier League and generally held to be one of the most temperamental, too; when he was good he was very, very good but when he was bad he was total crap. Abimbole’s leaving London City — during Zarco’s first tenure at the club — had been acrimonious, and prior to his departure relations with the Portuguese manager, who had bought him from the French club Lens, had become so bad that Abimbole had set fire to Zarco’s brand new Bentley in the club car park.

‘So what?’ said Zarco. ‘This particular Aaron doesn’t have a brother called Moses, so I don’t think we have anything to worry about.’

‘He’s already scored twenty goals for Newcastle this season,’ said Viktor. ‘That’s twice as many as he scored for us when he was here. Maybe we should worry about that.’

‘He’s lazy,’ insisted Zarco. ‘I never saw a lazier player, which is why clubs don’t keep him. He only scores when it’s up his back to do so but he never tracks back. Not like Rooney. You have Rooney, you have a great striker and a dogged defender. When you have Abimbole all you have is a lazy cunt.’

Clearly the United fans had thought the same way as Zarco; I remember watching him play for MU against Fulham and the fans singing, ‘ Abimbole, Abimbole, He’s a lazy arsehole, And he should be on the dole ’. You had to laugh.

‘Besides,’ added Zarco, ‘Scott here has a brilliant plan to fuck with his mind. Wait and see, boss. We’re going to put the hex on him.’

‘I’m glad to hear it.’

Viktor glanced at his watch; unlike the rest of us he wore a cheap Timex. The first time I’d seen it I’d checked it out on Google in case it was actually a valuable antique, but it cost just £7.50, which was another reason why I liked Viktor — most of the time he wasn’t in the least bit flashy; my suits from Kilgour were probably ten times more expensive than his. He was wearing the coat because it was cold. Only the billionaire’s Berluti shoes were expensive. And the Rolls-Royce Phantom in the car park, of course.

‘And now I’d best be going,’ he said. ‘I have an important meeting in the City. See you guys at the match on Saturday. Don’t forget, João, you’re coming to that pre-match lunch I’m hosting in the executive dining room for the RBG.’ RBG was the Royal Borough of Greenwich.

‘I wouldn’t miss it for the world, boss,’ said Zarco, drily.

‘Good. Because you’re the trophy guest,’ said Viktor. ‘At least you would be if we had any bloody trophies.’ Laughing, he walked back to the players’ tunnel, leaving the three of us staring at our much cheaper shoes.

‘Cheeky bastard,’ said Zarco.

‘He’s in a good mood,’ I replied.

‘I was just thinking the same thing,’ said Colin.

‘I know why, too,’ said Zarco. ‘This morning the RBG planning committee is going to announce that it has granted permission for the new Thames Gateway Bridge. It’s going to be worth a lot of money to Viktor’s company because they are building it, of course. That’s why he’s bringing the RBG council here for lunch on Saturday. To celebrate.’

‘But he’s paying for the bridge, isn’t he?’ I said. ‘Rather a lot if the newspapers are correct.’

‘He’s paying for some of it, yes. But don’t forget, the Thames Gateway is going to be a toll bridge. And the only bridge between Tower Bridge and the QEII Bridge. That’s exactly ten kilometres of river either side of where it will be built. Fifty thousand vehicles a day — that’s what they estimate. At five pounds a time, that’s two hundred and fifty grand a day, gentlemen.’

‘Five quid? Who’s going to pay that?’ asked Colin.

‘It costs six quid to get across the Severn Bridge into Wales.’

‘Surely it should be six quid to get out of Wales,’ I muttered.

‘It’s only two quid to go through the Dartford Tunnel,’ persisted Colin.

‘Yes, but it takes forever,’ I said.

‘That’s right,’ said Zarco. ‘So you do the math. They reckon the new bridge will make more than eighty million a year, just in tolls, and pay for itself in less than five years. You see? It only looks like philanthropy for five years, then it starts to look like very good business. He owns the bridge for the next ten years after that, before he gives it as a gift to the people of the RBG; but by then he’ll have made at least eight hundred million. Maybe more.’

‘No wonder he’s smiling,’ I said.

‘He’s not smiling,’ said Zarco. ‘He’s laughing. All the way to the Sumy Capital Bank of Geneva. Which, by the way, he also owns.’

‘That must come in handy when you need an overdraft,’ said Colin.

‘Did you hear that?’ Zarco shook his head and smiled, wryly. ‘Trophy guest, indeed. He never misses an opportunity to have a little dig at me.’

‘Talking of having a dig,’ said Colin, ‘that copper came back here, to the Crown of Thorns. Detective Inspector Neville. He wasn’t very pleased to see we’d filled in and grassed over the hole.’

‘What did he expect us to do with it?’ snarled Zarco. ‘Play around it?’

‘He said we should have let him know we were going to fill it in. That it was evidence. That they hadn’t had time to take a photograph.’

‘I’ll send him a photograph of a hole,’ I said. ‘Only it won’t be a hole in the ground.’

‘What did you tell him?’ asked Zarco. ‘The cop. You didn’t tell him about my photograph, I hope.’

‘No, of course not. Look, all I told him was what Scott told me to tell him. That he took full responsibility.’

‘What did he say to that?’

‘He said that suing the Metropolitan Police successfully had made you too big for your boots and that it was time someone took you down a peg or two.’

Читать дальше