Philip Kerr - January Window

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Philip Kerr - January Window» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2014, ISBN: 2014, Издательство: Head of Zeus, Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

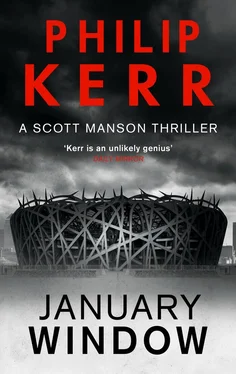

- Название:January Window

- Автор:

- Издательство:Head of Zeus

- Жанр:

- Год:2014

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-1-78408-153-9

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

January Window: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «January Window»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

But this time, it's murder.

Scot Manson: team coach for London City FC and all-round fixer for the lads. Players love him, bosses trust him.

But now the team's manager has been found dead at their home stadium.

Even Scott can't smooth over murder... but can he catch the killer before he strikes again?

January Window — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «January Window», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘You mean if I were to forget all about this?’

‘That’s right. We’ll just tell the press that the reports of a grave being found in the centre of London City’s football pitch have been greatly exaggerated. In fact, I insist on it. Come on. What do you say? Let’s just forget about it and go home. Doesn’t that sound like common sense?’

‘What it sounds like is bribery,’ Neville said stiffly. ‘At the risk of repeating myself, a crime has clearly been committed here, Mr Manson. And it’s beginning to look as if you really don’t want the police here at all. Which I admit does puzzle me, since it was someone from the club who summoned us here tonight.’

‘I’m afraid that was me,’ admitted Colin.

‘He made an honest mistake,’ I said. ‘And so did I when I offered you the tickets. I think I must have assumed that you were the kind of bloke who had something better to do than look into the mysterious case of the hole in the ground.’

‘You know what I think? I think you’re one of those people who just doesn’t like the police. Is that what you are, Mr Manson?’

‘Look,’ I said, ‘if you want a police medal for this then go ahead, be my guest. I was just trying to save you the effort of wasting police time on something that will almost certainly turn out to be a random incident of vandalism. And to save the club owner a bit of unnecessary embarrassment. But when did that sort of thing ever matter to the Met? Look, I think we’ve told you all we know. It sounds to me as if maybe we’ve got even less time to waste here than you have.’

‘Yes, you said. An FA Cup third round match against Leeds.’ He smiled. ‘I’m from Leeds myself.’

‘You’re a long way south, Inspector.’

‘Don’t I know it, sir. Especially when I listen to someone like you. I’m just trying to do my job here, Mr Manson, sir.’

‘And so am I.’

‘Only for some reason you’re making mine difficult.’

‘Am I?’

‘You know you are.’

‘Then go home. We’re not talking about The Arsenal Stadium Mystery here.’

‘That’s an old black and white film, isn’t it?’

I nodded. ‘1939. Leslie Banks. Piece of shit, really. Only interesting because the film stars several Arsenal players of the day: Cliff Bastin, Eddie Hapgood.’

‘If you say so, Mr Manson. Frankly I’ve never been much of a football fan myself.’

‘That was also my impression.’

Detective Inspector Neville paused thoughtfully for a moment and then pointed at me. ‘Wait a minute. Manson, Manson. You wouldn’t be...? Of course. You’re that Manson, aren’t you? Scott Manson. Used to play for Arsenal, until you went to prison.’

I said nothing. In my experience it’s always best when you’re talking to the police.

‘Yes.’ Neville sneered. ‘That would explain everything.’

7

Before I tell you anything about what happened to me in 2004 I should first tell you that I am part black — more of a David James or Clark Carlisle than Sol Campbell or Didier Drogba, but I think it’s probably relevant in view of what happened. In fact, I’m sure it is. I don’t consider myself black but I am a keen supporter of Kick it Out.

My dad, Henry, is a Scot who used to play for Heart of Midlothian and Leicester City. He got picked for Willie Ormond’s Scotland squad and went to the World Cup finals in West Germany in 1974 — the year we came so close. Dad didn’t play because of injury, which is probably how he found the time to meet my mother, Ursula Stephens, who was a former German field athlete — at the 1972 Munich Olympics she came fourth in the women’s high jump — working for German telly. Ursula is the daughter of an African-American air force officer stationed at Ramstein, and a German woman from Kaiserslautern. I’m happy to say that both my parents and my grandparents are still alive.

After finishing his career in football my dad set up his own sports boot and shoe company in Northampton, where I went to school, and in Stuttgart. The shoe company is called Pedila and today it generates almost half a billion dollars a year in net income. I earn a lot of money as a director of that company; it’s how I can afford a flat in Chelsea. My dad says I am the company’s ambassador in the world of professional football. But it wasn’t always like that. Frankly I wasn’t always the ambassador you would have welcomed in your executive toilet, let alone the boardroom.

In 2003, aged twenty-eight, I joined Arsenal from Southampton. The following year I went to prison for a rape I didn’t commit. What happened was this:

Back then I was married to a girl called Anne; she works in fashion and she’s a decent woman but to be honest, we weren’t ever suited. While I like clothes and am happy to drop £2k on a Richard James suit, I’ve never much liked high fashion. Anne thinks that people like Karl Lagerfeld and Marc Jacobs are artists. Me, I think that’s only half right. So while we were still living together we were already drifting apart; I was sure she was seeing someone else. I was doing my best to turn a blind eye to that, but it was difficult. We didn’t have any children, which was good since we were headed for a divorce.

Anyway, I’d started seeing a woman called Karen, who was one of Anne’s best friends. That was mistake number one. Karen was the mother of two children and she was married to a sports lawyer who had cancer. At first it was just me being nice to her, taking her out for the odd lunch to cheer her up, and then it got out of hand. I am not proud of that. But there it is. All I can say in my defence is that I was young and stupid. And, yes, lonely. I wasn’t interested in the kind of girls who throw themselves at footballers in nightclubs. Never have been. I don’t even like nightclubs. My idea of a nightmare is an evening out with the lads. I much prefer dinner at The Ivy or The Wolseley. Even when I was at Arsenal the club still had a reputation for some hard drinking — it wasn’t just silverware that the likes of Tony Adams and Paul Merson helped earn for the Gunners — but me, I was always in bed before midnight.

Karen’s house in St Albans was conveniently close to the Arsenal training ground at Shenley, so I’d got into the habit of dropping in to see her on my way home to Hampstead; and sometimes I was seeing a lot more of her than was proper. I suppose I was in love with her. And perhaps she was in love with me. I don’t know what we thought was going to happen. Certainly we could never have imagined what actually did happen.

I remember everything about the day it happened as if it has been etched onto my brain with acid. It was after one post-Shenley visit, a beautiful day near the end of the season. I came out of Karen’s house after a couple of hours to find that my car had been nicked. It was a brand new Porsche Cayenne Turbo that I’d only just taken delivery of, so I was pretty gutted. At the same time I was reluctant to report the car stolen for the simple reason that I guessed my wife, Anne, would recognise Karen’s address if the story got into the newspapers. So I jumped on a train back to my house in Hampstead, thinking I might as well report the car stolen from somewhere in the village. Mistake number two. However, no sooner had I got back home than Karen rang me and said the car was now standing outside her house again. At first I didn’t believe it, but she read out the registration number and it was indeed my car. More than a little puzzled as to what was happening, I got in a taxi and went straight back to St Albans to collect it.

When I arrived there I couldn’t believe my luck. The car wasn’t locked but it didn’t have a scratch on it and, anxious to be away from Karen’s house before her husband came home, I drove off telling myself that perhaps some kids had taken it for a joy-ride and then returned it, having had second thoughts about what they’d done. Oddly enough I’d done something like that as a kid: I stole a scooter and then returned it after a couple of hours. It was naïve of me to think that something similar had happened here, I admit, but I was just happy to be reunited with a car I loved. Mistake number three.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «January Window»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «January Window» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «January Window» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.