Ah. Got it. She’d been wondering.

‘Working, busy, not the prettiest city in the country, not by a long shot. But it has energy and a certain charm. Not to mention The Last Supper . The fashion world. And La Scala. Do you like opera?’

‘Not really.’

A pause. Its meaning: How could someone with a pulse not like opera?

‘Too bad. I could get tickets to La Traviata tonight. Andrea Carelli is singing. It wouldn’t be a date.’ He said this as if waiting for her to blurt, ‘No, no, a date would be wonderful.’

‘Sorry. I’ve got to get back tonight, if possible.’

‘Charlotte said you’re working on the case. The kidnapper.’

‘Right.’

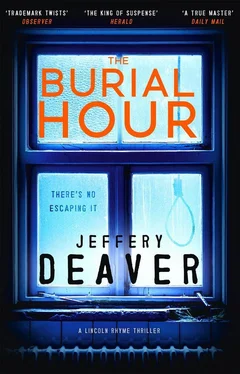

‘With the famous detective, Lincoln Rhyme. I’ve read some of those books.’

‘He doesn’t like them very much.’

‘At least people write about him. Nobody’s going to write novels about a legal liaison, I don’t think. Though I’ve had pretty interesting cases.’

He didn’t elaborate — she was pleased about that — but concentrated on his GPS. Traffic grew worse and Prescott swung down a side road. In contrast with this, the trip from Naples to Milan had been lightning-fast. Computer millionaire Mike Hill’s driver, a larger-than-life Italian with thick hair and an infectious smile, had met her outside the hotel, where he’d been waiting with a shiny black Audi. He’d leapt forward to take her bag. In a half hour, after an extensive history lesson on southern Italy, delivered in pretty good English and with more than a little flirt, they had arrived at the private aircraft tarmac in Naples. She’d climbed onto the plane — even nicer than the one they’d flown to Italy on — and soon the sleek aircraft was streaking into the air. She’d had a pleasant conversation with one of Hill’s executives, headed to Switzerland for meetings. Pleasant, yes, though the young man was a super geek and often lost her with his enthusiastic monologues about the state of high technology.

Prescott was now saying, ‘I prefer Milan, frankly, to other cities here. Not as many tourists. And I like the food better. Too much cheese in the south.’

Having recently been served a piece of mozzarella that must’ve weighed close to a pound, she understood, though was tempted to defend Neapolitan cuisine. An urge she declined.

He added, ‘But here? Ugh, the traffic.’ He grimaced and swung the car onto a new route, past shops and small industrial operations and wholesalers and apartments, many of whose windows were covered with curious shades, metal or mesh, hinged from the top. She tried to figure out from the signage what the many commercial operations manufactured or sold, with limited success.

And, yes, it did resemble parts of Chicago, which she’d been to a few times. Milan was a stone-colored, dusty city, now accented with fading autumn foliage, although the dun tone was tempered by ubiquitous red roofs. Naples was far more colorful — though also more chaotic.

Like Hill’s swarthy, enthusiastic driver, Prescott was happy to lecture about the nation.

‘Just like the US, there’s a north/south divide in Italy. The north’s more industrial, the south agricultural. Sound familiar? There’s never been a civil war, as such, though there was fighting to unify the different kingdoms. A famous battle was fought right here. Cinque Giornate di Milano. Five Days of Milan. Part of the first War of Independence, eighteen forties. It drove the Austrians out of the city.’

He looked ahead, saw a traffic jam, and took a sharp right. He then said, ‘That case? The Composer. Why’d he come to Italy?’

‘We’re not sure. Since he’s picked two immigrants, refugees, so far, he might be thinking it’s harder for the police to solve the cases with undocumenteds as victims. And they’re less motivated to run the investigation.’

‘You think he’s that smart?’

‘Every bit.’

‘Ah, look at this!’

The traffic had come to a halt. From the plane, she’d called Prescott and given him the address on the Post-it note found at the scene where the Composer had slashed Malek Dadi to death. Prescott assured her that it would take only a half hour to get there from the airport but already they’d been fighting through traffic for twice that.

‘Welcome to Milano,’ he muttered, backing up, over the sidewalk, turning around and finding another route. She recalled that Mike Hill had warned about the traffic from the larger airport in Milan, thinking: Imagine how long it would take to fight twenty-some miles of congestion like this.

Nearly an hour and a half after she’d landed, Prescott turned along a wide, shallow canal. The area was a mix of the well-worn, the quirky chic and the tawdry. Residences, restaurants and shops.

‘This is the Navigli,’ Prescott announced. He pointed to the soupy waterway. ‘This and a few others are all that’re left of a hundred miles of canals that connected Milan to rivers for transport of goods and passengers. A lot of Italian cities have rivers nearby or running right through town. Milan doesn’t. This was the attempt to create artificial waterways to solve that problem. Da Vinci himself helped design locks and sluices.’

He turned and drove along a quiet street to an intersection of commercial buildings. Deserted here. He parked under what was clearly a no-parking sign, with the attitude of someone who knew beyond doubt he wouldn’t be ticketed, much less towed.

‘That’s the place right there: Filippo Argelati, Twenty Thirty-Two.’

A sign, pink paint — faded from red: Fratelli Guida. Magazzino.

Prescott said, ‘The Guida Brothers. Warehouse.’

The sign was very old and she guessed that the siblings were long gone. Massimo Rossi had texted her that the building was owned by a commercial real estate company in Milan. It was leased to a company based in Rome but calls to the office had not been returned.

She climbed out of the car and walked to the sidewalk in front of the building. It was a two-story stucco structure, light brown, and covered with audacious graffiti. The windows were painted dark brown on the inside. She crouched down and touched some pieces of green broken glass in front of the large double doors.

She returned and Prescott got out of his vehicle too. She asked, ‘Could you stay here and keep an eye on the neighborhood. If anyone shows up text me.’

‘I...’ He was flustered. ‘I will. But why would anyone show up? I mean, it looks like nobody’s been there for months, years.’

‘No, somebody was here within the past hour. A vehicle. It ran over a bottle that was in front. See it? That glass?’

‘Oh, there. Yes.’

‘There’s still wet beer inside.’

‘If there’s something illegal going on, we should call the Carabinieri or the Police of State.’ Prescott had grown uncomfortable.

‘It’ll be fine. Just text.’

‘I will. Sure. I’ll definitely text. What should I text?’

‘A smiley emoji’s fine. I just need to feel the vibration.’

‘Feel... Oh, you’ll have the ringer off. So nobody can hear? In case anybody’s inside?’

No confirmation needed.

Sachs returned to the building. She stood to the side of the door, her hand near the Beretta grip in her side pocket. There was no reason to think the Composer had tooled up to Milan in his dark sedan, crunched the bottle pulling into the warehouse and was now waiting inside with his razor or knife or a noose handy.

But no compelling reason not to think that.

She pounded on the door with a fist, calling out a reasonable, ‘ Polizia! ’

Proud of herself, getting the Italian okay, she thought. And ignoring that she was undoubtedly guilty of a serious infraction.

Читать дальше