Ercole grimaced. ‘The woman is quite insopportabile . You say, intolerable?’

‘Yes, or insufferable.’

‘ Sì , insufferable is better! I asked her several times of her progress and she glared at me. And I wished to know if you can fingerprint the bark of a tree. An innocent question. Her expression, frightening. As if saying, “Of course you can! What fool doesn’t know that?” And can she not smile? How difficult is that?’

Lincoln Rhyme was not one to turn to for sympathy in matters like this. ‘And?’ he asked impatiently.

‘No, nothing, I’m afraid. Not yet. She and her assistants are working hard, however. I will give her that.’

Ercole ordered something from the waitress and a moment later an orange juice appeared.

Rhyme said, ‘Well, we have another situation we need help with.’

‘You have more developments about our musical kidnapper?’

‘No. This is a different case.’

‘Different?’

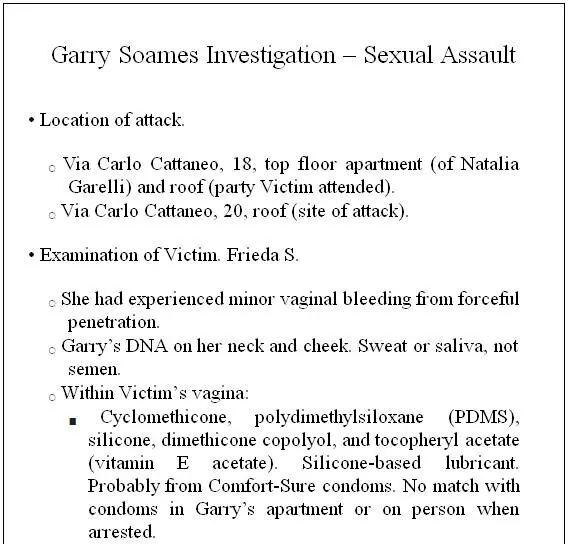

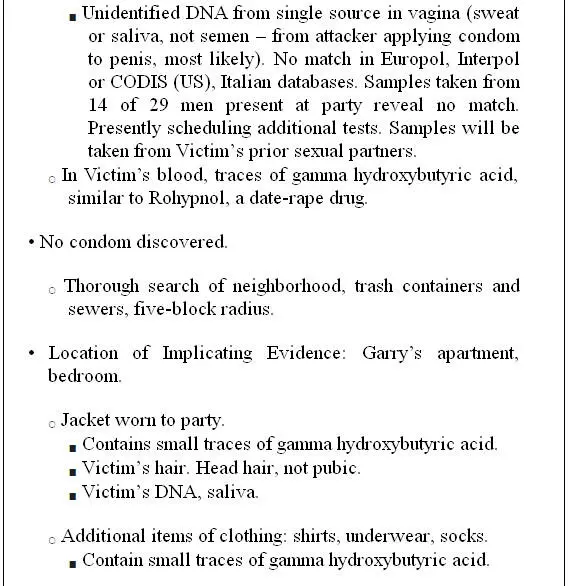

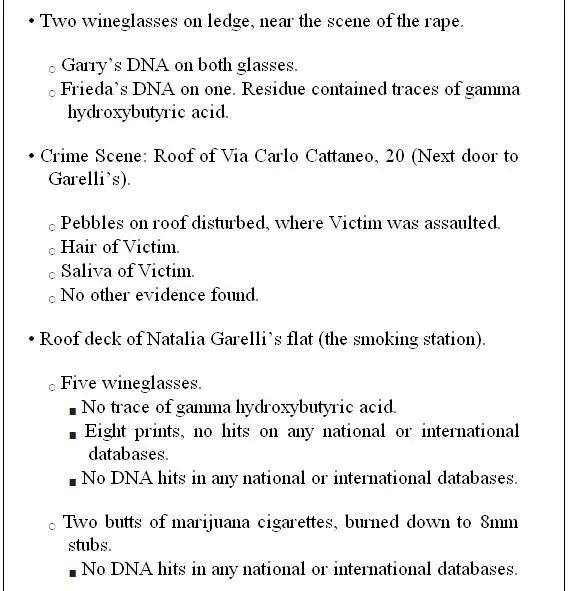

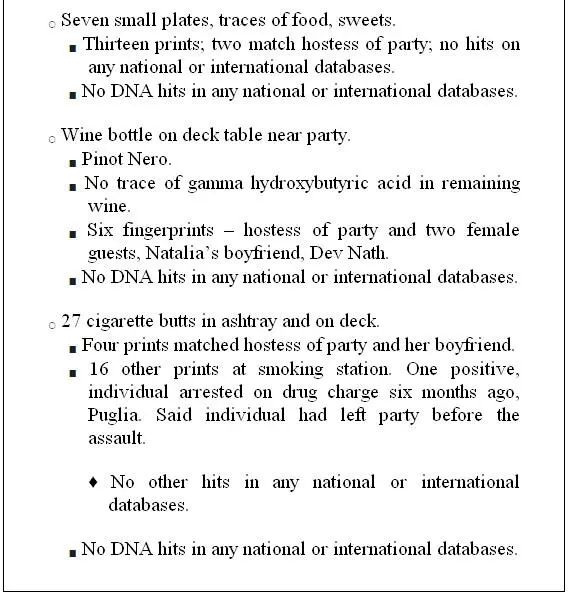

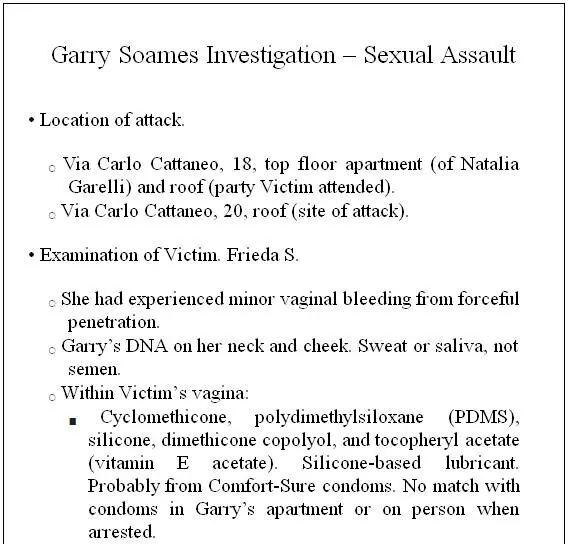

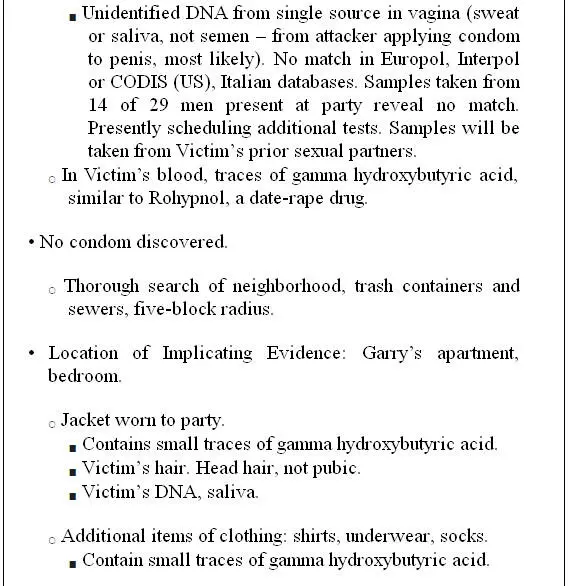

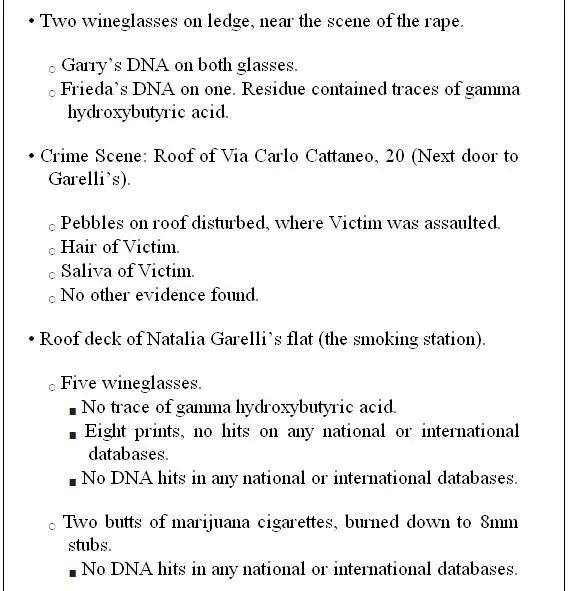

On the small table before them Sachs was spreading out documents: copies of the crime scene reports and interviews regarding the rape Garry Soames was accused of, provided by the lawyer he and his family had retained.

‘We need translations of these reports, Ercole.’

He looked them over, shuffled through them. ‘How does this connect to the Composer?’

‘It doesn’t. Like I said, it’s another case.’

‘Another...?’ The officer chewed his lip. He read more carefully. ‘Yes, yes, the American student. This is not one of Massimo Rossi’s cases. It’s being run by Ispettore Laura Martelli.’ He nodded at the Questura.

Rhyme said nothing more and Sachs added, ‘We’ve been asked by a State Department official to review the evidence. The defendant’s lawyer’s convinced the boy is innocent.’

Ercole sipped his orange juice, which — like most non-coffee beverages in Italy, Rhyme had observed — had been served without ice. And Coca-Cola always came with lemon. The Forestry officer said, ‘Oh, but, no. I cannot do this. I am sorry.’ As if they’d missed something blatantly obvious. ‘You do not see. This would be un conflitto d’interesse . A—’

Rhyme said, ‘Not really.’

‘No. How is that possible?’

‘It would be, no, it might be a conflict of interest if you were working for the Police of State directly. But you are, technically, still a Forestry officer, isn’t that right?’

‘Signor Rhyme, Capitano Rhyme, that is not a defense that will be very persuasive at my trial. Or will stop Prosecutor Spiro from beating me half to death if he finds out. Wait... who is the procuratore ?’ He flipped through the pages. And closed his eyes. ‘ Mamma mia! Spiro is the prosecutor. No, no, no. I cannot do this! If he finds out, he will beat me fully to death!’

‘You’re exaggerating,’ Rhyme reassured, though he admitted to himself that Dante Spiro seemed fully capable of a blow or two.

Difficult, vindictive, cold as ice...

‘Besides, we’re simply asking you to translate. We could hire someone but it will take too long. We want to look over the evidence quickly, give our assessment and get back to the Composer. There’s no reason for Dante to find out.’

Sachs added, ‘This is very likely a case of an innocent American student in jail for a crime he didn’t commit.’

He muttered, ‘Ah, we had a case like that a few years ago. In Perugia. It did not go well for anybody.’

Rhyme nodded to the file. ‘And the evidence may very well prove Soames is guilty. In which case we will have done the prosecution and the government a service. At no charge.’

Sachs: ‘Please. Just translation. What’s the harm in that?’

With a resigned look on his face, Ercole pulled the papers forward and, with a glance around, as if Spiro were hiding in the shadows nearby, began to read.

Rhyme said, ‘Make a chart, a mini chart.’

Sachs dug into her computer bag and pulled out a yellow legal pad. She uncapped a fine-pointed marker and looked toward Ercole. ‘You dictate and I’ll write.’

‘I am still an accessory to a crime,’ he whispered.

Rhyme only smiled.

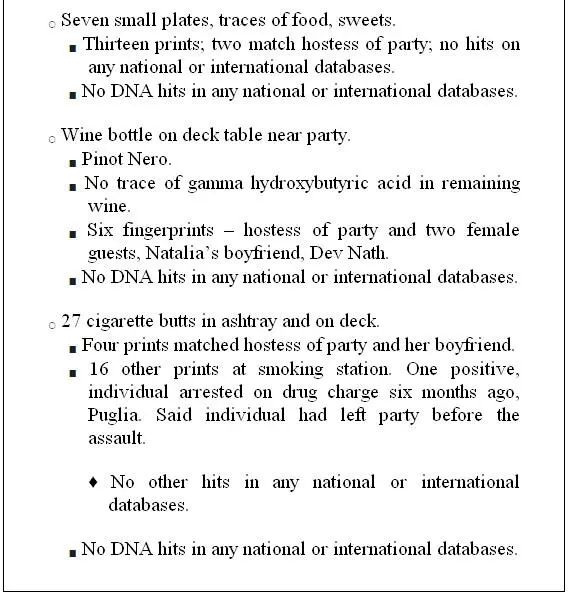

When she had finished writing, they looked the pad over. Rhyme reflected: Solid work. He would have liked to have samples of the trace from the deck or roof area where the smoking station was located, and from the site of the attack itself. But this was good for starters.

Sachs glanced at the remaining pages of notes in Italian Ercole was staring at, the official report. ‘Go on,’ she insisted kindly. ‘Please. I want to hear the accounts.’

Ercole apparently hoped he’d be let off the hook by simply translating the forensics. Reciting the witnesses’ and suspect’s statements seemed perhaps, in the young officer’s mind, to move his crime into a different category, misdemeanor to felony.

Reading, he said, ‘Natalia Garelli, twenty-one, attends the University of Naples. She hosted a party in her flat for fellow students and friends. The victim, Frieda S., arrived at ten p.m. Alone. She remembered drinking and talking with some people — mostly Natalia or her boyfriend — but was a bit shy. She too is a student, just arrived from Holland. She vaguely recalls around eleven or midnight the defendant approaching her and talking. They both had glasses of wine at the table where they were sitting — this is downstairs — and Garry kept refilling her glass. Then they embraced and... limonarono... I do not know.’

‘Made out?’ Sachs suggested.

‘ Sì. Made out.’ He read more. ‘It was crowded so they went to the roof. Then Frieda has no memory until four in the morning, waking on the roof of the adjacent building and realizing she’d been assaulted. She was still quite drugged but managed to get to the wall separating the two rooftops. She climbed over, fell and was calling for help. Natalia, the hostess, heard her cries and got her downstairs into the apartment. Natalia’s boyfriend, Dev, called the police.

‘Investigators checked the door to the roof of the adjoining building but it was locked and did not appear to have been opened recently. Natalia told police that she suspected Serbian roommates living downstairs in that building — they’d been crude and drank a lot — but the police verified they were out of town. And dismissed anyone else in that building as suspects.

‘A few witnesses on the roof — at the table for smoking, the smoking station — saw Garry and Frieda together briefly, walking to an alcove on the roof, where there was a bench, but that is out of sight of the smoking station. Between about one a.m. and two, only they were upstairs. At two a.m. Garry walked down the stairs to the apartment proper and left. Several witnesses reported that he seemed distressed. No one noticed that Frieda was missing. People assumed she’d left earlier. The next day there was an anonymous call — a woman, calling from a pay phone at a tabaccaio near Naples University. After she heard about the attack, she wanted to call the police and report that she believed she’d seen Garry mixing something into Frieda’s drink.’

Читать дальше