What should I do and say? I’d tell Alex the truth if we were alone.

“Dad? Accelerate? Like, you’re holding everyone up. Ugh! I said ‘like’ again, goddammit.”

“Don’t say ‘goddammit’ either,” Alex tells her.

“Don’t let me watch The Good Wife , then. And you two swear all the time , hypocrites.”

The car creeps forward, then picks up speed. I feel braver as soon as I know it’s no longer possible for me to see 8 Panama Row. “That was . . . strange,” I say. The strangest thing that has ever happened to me. I exhale slowly.

“What, Mum?”

“Yes, tell us, goddammit.”

“Dad! Objection! Sustained.”

“Overruled, actually. You can’t sustain your own objection. Anyway, shush, will you?”

Shush. Shut up, shut up, shut up. It’s not funny. Nothing about this is funny.

“Justine, what’s the matter with you?” Alex is more patient than I am. I’d be raising my voice by now.

“That house. You pointed, and I looked, and I had this . . . this overwhelmingly strong feeling of yes. Yes, that’s my house. I wanted to fling open the car door and run to it.”

“Except you don’t live there, so that’s mad. You don’t live anywhere at the moment. Until this morning you lived in London, and hopefully by this evening you’ll live just outside Kingswear in Devon, but you currently live nowhere.”

How appropriate. Do Nothing, live nowhere.

“You certainly don’t live in an interwar semi beside the A406, so you can relax.” Alex’s tone is teasing but not unkind. I’m relieved that he doesn’t sound worried. He sounds less concerned now than he did before; the direction of travel reassures me.

“I know I don’t live there. I can’t explain it. I had a powerful feeling that I belonged in that house. Or belonged to it, somehow. By ‘powerful,’ I mean like a physical assault.”

“Lordy McSwordy,” Ellen mumbles from the back seat.

“Almost a premonition that I’ll live there one day.” How can I phrase it to make it sound more rational? “I’m not saying it’s true. Now that the feeling’s passed, I can hear how daft it sounds, but when I first looked, when you pointed at it, there was no doubt in my mind.”

“Justine, nothing in the world could ever induce you to live cheek by jowl with six lanes of traffic,” says Alex. “You haven’t changed that much. Is this a joke?”

“No.”

“I know what it is: poverty paranoia. You’re worried about you not earning, us taking on a bigger mortgage . . . Have you had nightmares about losing your teeth?”

“My teeth?”

“I read somewhere that teeth-loss dreams mean anxiety about money.”

“It isn’t that.”

“Even poor, you wouldn’t live in that house—not unless you were kidnapped and held prisoner there.”

“Dad,” says Ellen. “Is it time for your daily You’re-Not-Helping reminder?”

Alex ignores her. “Have you got something to drink?” he asks me. “You’re probably dehydrated. Heatstroke.”

“Yes.” There’s water in my bag, by my feet.

“Drink it, then.”

I don’t want to. Not yet. As soon as I pull out the bottle and open it, this conversation will be over; Alex will change the subject to something less inexplicable. I can’t talk about anything else until I understand what’s just happened to me.

“Oh no. Look: roadwork.” When Alex starts to sing again, I don’t know what’s happening at first, even though it’s the same tune from Carmen and only the words have changed. Ellen joins in. Soon they’re singing in unison, “Hard hats and yellow jackets, hard hats and yellow jackets, hard hats and yellow jackets, boo . Hard hats and yellow jackets, hard hats and yellow jackets, boo, sod it, boo, sod it, boo . . .”

Or I could try to forget about it. With every second that passes, that seems more feasible. I feel almost as I did before Alex pointed at the house. I could maybe convince myself that I imagined the whole thing.

Go on, then. Tell yourself that.

The voice in my head is not quite ready. It’s still repeating words from the script I’ve instructed it to discard:

One day, 8 Panama Row—a house you would not choose in a million years—will be your home, and you won’t mind the traffic at all. You’ll be so happy and grateful to live there, you won’t be able to believe your luck.

FOUR MONTHS LATER

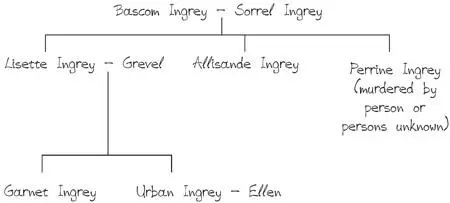

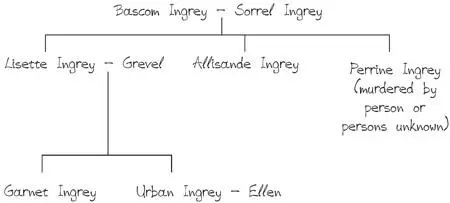

FAMILY TREE

The Ingreys of Speedwell House

Murder Mystery Story

by Ellen Colley, Class 9G

Chapter 1

~

The Killing of Malachy Dodd

Perrine Ingrey dropped Malachy Dodd out of a window. She wanted to kill him and she succeeded. Later, no one believed her when she screamed, “I didn’t do it!” Both of their families, the Ingreys and the Dodds, knew that Perrine and Malachy had been upstairs in a room together with no one else around.

This was Perrine’s bedroom. It had a tiny wooden door (painted mint green, Perrine’s favorite color) next to her bed. This little door was the only way of getting from one part of the upstairs of Speedwell House to the other unless you wanted to go back downstairs, through the living room and the library, and then climb up a different lot of stairs, and no one ever wanted to do that. They preferred to bend themselves into a quarter of the size of the shortest dwarf in the world (because that was how tiny the mint-green door was) and squeeze themselves through the minuscule space.

After she dropped Malachy out of the window and watched him fall to his gory death on the terrace below, Perrine squashed herself through the tiny green door and pulled it shut behind her. When her parents found her huddled on the landing on the other side, she exclaimed, “But I wasn’t even in the room when it happened!”

Nobody was convinced. Perrine hadn’t been clever enough to move a decent distance away from the door, so it was obvious she had just come through it. Her second mistake was to yell, “He fell out by accident!” For one thing Malachy was not tall enough to fall out of the window accidentally (all the adults agreed later that his center of gravity was too low) and for another, if Perrine wasn’t in the room when it happened, how did she know that he fell by accident?

A third big clue was that every single other person who might have murdered Malachy was downstairs in the dining room at the time of his hideous death. All of the Dodds were there, and all the Ingreys apart from Perrine. Her two older sisters, Lisette and Allisande, were sitting in chairs facing the three sets of French doors that were open onto the terrace where Malachy fell, splattering his red and gray blood and brains on the ground beside the fountain. It felt as if his falling shook the whole house, especially the French “purple crystals” chandelier above Lisette and Allisande’s heads, but that must have been an illusion.

Lisette and Allisande definitely saw Malachy fall and smash, however, and, what’s more, they heard a loud, triumphant “Ha!” floating down from above. Both of them recognized the voice of their younger sister, Perrine.

So, if all the other possible suspects were in the dining room, who else apart from Perrine Ingrey could have been responsible for Malachy landing in a heap on the paving slabs? I’ll tell you who: nobody.

There was no doubt that Perrine killed him, however much she wailed that she was innocent. (The death of Malachy Dodd is not the murder mystery in this story. The mystery is who murdered Perrine Ingrey, because she went on to get murdered too, but that comes later.)

Читать дальше