For Marietta von Bernuth and David Esterly

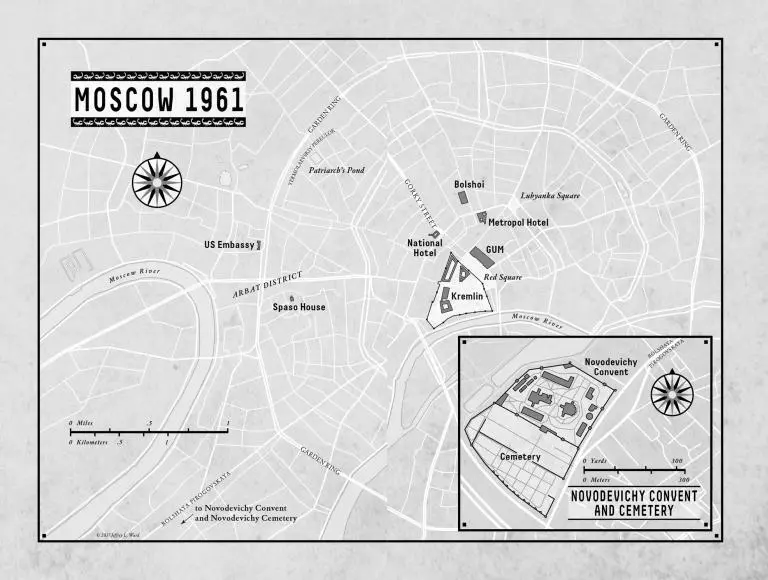

MOSCOW, 1961

IT WAS STILL LIGHT when they landed at Vnukovo, the late northern light that in another month would last until midnight. There had been clouds over Poland but then just patches so you could see the endless flat country below, where the German tanks had rolled in, all the way to the outskirts of Moscow, nothing to stop them, the old fear come true, the landscape of paranoia. Even from the air it looked scrubby and neglected, dirt tracks and poor farmhouses, then factories belching brown lignite smoke. But what had he expected? White birch forests, troika races over the snow? It was the wrong season, the wrong century.

There was no seat belt sign. Simon felt the descent, then the bump and skid of wheels on the runway, and looked out the window. Any airport—a terminal and a tower, some outlying buildings, no signs.

“Sheremetyevo?” he asked his—what? handler? A human visa, someone the Russians had sent to Frankfurt to travel with him.

“No, Vnukovo. VIP airport,” he said, evidently meaning to impress.

But in the fading light it seemed dreary, empty runways with clumps of grass running along the edges, a lone signalman in overalls waving them away from the main terminal. They taxied to one of the other buildings.

“No customs,” his handler said, part of the VIP service.

Simon peered out, his face pressed against the plastic window. What would he look like now? Twelve years. In the one picture Simon had seen, the one the wire services had picked up and sent around the world, he’d been wearing a Russian fur hat, flaps up, and a double-breasted coat, the onion domes of St. Basil’s just over his shoulder, the kind of picture authors used on book jackets. But now it was spring, no heavy clothes to hide behind. He’d be Frank. If he was there. So far nobody, just the empty tarmac, away from the bother of customs. It occurred to Simon then that they didn’t want anyone to know he’d come, shuttling him off to an out building, whisking him away in some dark car like an exchanged prisoner, as if he’d been the spy, not Frank. Maybe they’d anticipated reporters and flashbulbs, the foreign press still fascinated by Frank. The man who betrayed a generation. Twelve years, a lifetime, ago. But nobody had told them. This end of the runway was empty, just two airport workers wheeling a staircase up to the plane. Someone was coming out of the building now, heading toward them, a soldier’s rigid shoulders. Not Frank.

Simon put on his coat and headed for the door, his handler following with the luggage. How could Frank not come to the airport? His brother. And now his publisher, the one Frank had asked for, arranging the visa to come work on the memoirs, an excuse to see him, maybe even explain things, all these years later. Things you couldn’t say in a book, not one that would have to pass his bosses’ vetting. Line by line in some office at the Lubyanka. Well, but hadn’t we done the same thing? Pete DiAngelis in the small conference room, making notes.

“We have to be sure our people aren’t compromised,” DiAngelis had said. “You understand.” His tone suggesting that Simon didn’t, that he was some kind of traitor himself, aiding and abetting. An opportunist too greedy to realize what was at stake.

“He doesn’t mention any agents by name. Not active ones. He’s not trying to give anyone away.”

“No? That didn’t stop him before. He write about that? The people he set up? The ones who didn’t come back?”

“See for yourself,” he said, gesturing to the manuscript. “It’s about him. Why he did it.”

“Why did he?” DiAngelis said, goading.

Simon shrugged. “He believed in it. Communism.”

“Believed in it. And now he’s going to say he’s sorry? Except he’s not. My Secret Life. Here’s my side. And screw you. For two cents I’d shut the whole thing down. Who gives a fuck what he believes?”

“People. Let’s hope so anyway.”

“Or you’re out some cash, huh?” He looked straight at Simon. “Paying him. Making him rich. For fucking us over. Freedom of the press.”

Simon nodded at him, a silent “as you say.”

“Don’t think anybody’s happy about this. He wants to make the Agency look bad, all right. Who the fuck would believe him anyway? But if he names any of our guys, even hints—”

“We take it out. You think I’d want to endanger anyone in the field?”

“I don’t know what you’d want.”

“There’s nothing like that in there. Read it. The other side already has, don’t you think? So now it’s your turn. Just leave something for the rest of us, okay?”

Another look. “One thing. Satisfy my curiosity. How’d you twist the Agency’s arm? Get them to go along with this?”

“Are they going along? I thought that’s what you were here for. Throw red flags all over the field.”

In fact, it was Look whose involvement had given the Agency the needed push, the promise of publicity, even a court fight, if they tried to stop publication. The Digest, the Post, wouldn’t even look at an excerpt, and though Luce was tempted, sensing a story big enough for a special issue, he finally fell back on principle too (“we don’t publish Communist spies”), which left Look and the serial sale that made the deal happen. Without that, Simon never could have raised the money the Russians were asking. More than M. Keating & Sons had paid for anything, a pile of chips all shoved now on red, for what had to be a best seller. Diana’s father, a Keating son, had reservations, but in the end went along with Simon. What choice did he have? After Frank’s defection, Simon had had to resign from the State Department, and it was Keating who’d come to the rescue, offering him a career in publishing. Now Simon was running the company, Keating just a genial presence at the Christmas party. Too late now to change succession plans.

“You realize this is a first draft?” Simon said to DiAngelis. “You’re just going to have to go through it again when I get back. So leave something.”

“There’s more? You want him to put stuff in?”

“I want to know what he did. Actually did. Besides defect. That’s all anybody knows really. That he—”

“Ran,” DiAngelis finished. He looked at Simon. “You want him to be innocent. He wasn’t.”

“No,” Simon said. “He wasn’t.”

But he had been once. You could see it in the old home movies, the boys like colts trying to stand on wobbly legs, making faces at the camera. In the end Simon became the taller, but when they were boys it was Frank who had the crucial extra inch, just as he had the extra year. The films, jerky and grainy, showed them opening Christmas presents, dodging waves at the beach, waving down from the tree at their grandmother’s house, and in all of them Simon was trailing after Frank, a kind of shadow, his partner in crime. Frank knew things. Where to find clams in the mud flats. How to get extra hot fudge sauce at Bailey’s. How to skim their father’s pocket change without his knowing or missing it. Years of this, in the old house on Mt. Vernon Street, bedrooms separated by a narrow hall, the model train running between, so that it really seemed like one room.

Читать дальше