“Never figured you for a soldier of fortune, Soc.”

“Me neither. That’s why I’m no longer on his payroll. Ruskin has another guy working for him. First name is Dudley. Maybe Australian. I know that isn’t much.”

“Give me a minute. I’ll look in the bad guy database.” He hung up. I could imagine him tapping into the vast intelligence network he had at his fingertips. He called back after three minutes. “He’s an Aussie named Dudley Wormsley, AKA ‘The Worm.’ Interpol has a pile of warrants out for him.”

“I thought as much. Wonder if there is any way to let the FBI know that ‘The Worm’ is sitting in the Harwich, Massachusetts police station, under arrest for breaking and entering.”

“I’ll take care of it. When we going fishing?”

“Charter boat’s coming out of the water, but there’s my dinghy. As you know, I don’t bait my hooks.”

“Suits me,” Flagg said.

I hung up and thought about Mike. He said he’d been attacked by goats . Dudley had referred to the hazmat suit as a spook suit. Spooks equal ghosts. Which meant plural. Which meant he wasn’t alone. Which meant the second ghost was Ruskin.

With Dudley out of the way, Ruskin was an open target, if I could get to him, although that was unlikely given the air-tight fortress he lived in. When I got home I retrieved the box from the deck and brought it inside. I took out the plastic case protecting the merganser, put it on the kitchen table and stared at it, taking in the graceful lines of the bird’s body and neck.

“Talk to me,” I said.

Early the next morning I got up, poured some coffee into a travel mug, and called Ruskin’s number. The butler answered the phone and said his boss was busy. I said that was all right. I merely wanted to drop off Mr. Ruskin’s decoy. He said to leave it at the gatehouse.

After hanging up, I got a small leather case out of a duffle bag I keep in my bedroom closet. Inside the case was a full range of lock picks. After a few tries, I popped the padlock and lifted the box lid back on its hinges. I remembered how Ruskin had reached into the box for the carving and lifted it above his head.

Then I took the decoy out of the box, put it in the sink and got a jar of peanut butter out of the refrigerator. I spooned some butter out of the jar onto the bird carving and smeared it all over the wooden feathers with my hands. Then I nestled the glistening fake bird back into its fake nest. I padlocked the box again and carried it out to the truck.

As I drove away from the gatehouse after dropping the box off for Mr. Ruskin, I thought what I’d done was rather sneaky and not very nice. Maybe Ruskin was allergic to peanuts. Maybe not. But I didn’t like being played for a patsy, especially when innocent people are hurt. It happened at a village in Vietnam, and with Murphy. It wasn’t going to happen again.

I stopped by the hospital on the way home. Mike was out of the ICU and sleeping. The nurse in charge said he was doing fine.

Bridget called me that night to say that she had been trying to reach Ruskin, but his butler said he wasn’t available. She said she would keep me posted. I didn’t know what Ruskin was allergic to when I returned his decoy. Maybe I just got lucky.

Mike got out of the hospital a few days later. I drove him home and checked in on him while he healed and popped painkillers. When I asked why he had called me instead of 911, he said it was because Marines stick together.

Once he was able to talk at length we discussed what to do about the Crowell decoy.

He confessed that he’d taken it from the Orloff mansion for payment of back wages. When he found out the bird was worth maybe a million dollars, he knew he couldn’t sell it. He read about Chinese reproductions somewhere and went into the fake decoy business for himself. He had the original scanned in New York and made in China. He sold out the first batch except for the one he kept. But he started to get nervous about attracting attention to himself and wanted the Crowell bird out of the house. He hid it in plain sight at the historical society museum, never figuring they’d put it in the Crowell barn.

“Legally speaking, the bird belongs to Ruskin,” I said. “He told me that he paid Orloff for the merganser, but I have only his word for that. It’s quite possible no money exchanged hands, which means that the sale never went through. In that case, Orloff was still the owner. Did he have any heirs?”

“None that I know of. He left lots of folks holding the bag. Including me. But if I admit I took it from the house, I could get into trouble.”

Mike was right. He’d removed the bird without permission. His sticky fingers saved the carving, but it was still grand larceny. If the debtors heard about the bird, they’d want it put up for auction so they could get a cut, no matter how small.

I thought about it for a minute. “You mentioned a fund for handicapped children that Orloff cheated,” I said.

“Big time. They’ll never recover.”

“They might,” I said. “Suppose we contact their lawyers and say we have the bird. Tell them that Orloff felt remorse over cheating the fund, and he wanted to donate proceeds from the sale of the Crowell at auction.”

“Great, but how does that explain me having the bird?”

“You’re a bird carver. Orloff let you take the bird so you could prepare a prospectus at auction. When he went to jail and the house was sealed, you didn’t know what to do. Orloff called and told you he wanted to move ahead with the sale, then he died.”

“That old bastard never said that. Never would.”

“Maybe, but that’s the way you understood it. It makes him look good, and helps a bunch of kids who need it. Splitting it among the debtors would only make the lawyers rich. Look at it this way: the Marines have landed and the situation is well in hand. Semper fi.”

Mike shook my hand with a lobster grip.

“Semper fi.”

Mike’s new implants look like the real thing. They should. I used Ruskin’s check to help pay for them. It was the least I could do, but left me with nothing for the boat loan. I was drowning my sorrows in a beer at Trader Ed’s one night when another boat captain offered me a job crewing on a charter boat in the Florida Keys. I said I’d take it. The timing was good. Bridget called the other day to let me know the Ruskin job was permanently off.

Sometimes I wonder what Crowell would have made of the whole affair. He’d be puzzled at all the fuss over one of his birds, but I think he’d be pleased how things turned out with the preening merganser.

The knees of the gods, as Homer said.

Or my partner Sam used to say after a good day of fishing: “Finestkind, Cap.”

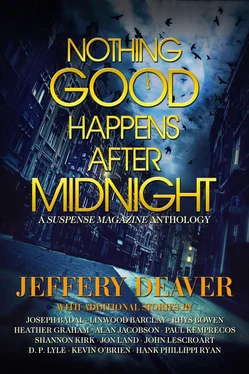

A Creative Defense

Jeffery Deaver

She hadn’t wanted to go.

Though she was an academic at a school with a “fine fine-arts program,” as she joked, classical music wasn’t really Beth Tollner’s thing.

Pop, sure. Jazz. Even soft rap, a phrase she coined herself.

Musicals, of course.

Wicked, In the Heights, Hamilton...

She and Robert were, after all, only in their late twenties. Wasn’t classical for fogies?

Then she’d reflected: That wasn’t fair to those of middling age. Most classical was just boring.

But Robert had been given a couple of tickets from one of the partners at the firm where he was a young associate, and he thought it would be political to attend and report back to his boss how much they liked the performance.

Beth had thought: What the hell? Why not get a little culture?

And nothing wrong with dressing up a bit more than you would to see Van Halen or Lady Gaga. She pinned her blonde hair up and picked a black pant suit — Robert wore navy, lawyer attire sans tie. Quite the handsome couple, she thought, catching a glimpse of themselves in the mirror.

Читать дальше