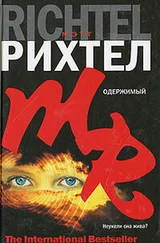

Мэтт Рихтел - Dead on Arrival

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Мэтт Рихтел - Dead on Arrival» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2017, ISBN: 2017, Издательство: William Morrow, Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Dead on Arrival

- Автор:

- Издательство:William Morrow

- Жанр:

- Год:2017

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-06-244327-4

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Dead on Arrival: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Dead on Arrival»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Dead on Arrival — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Dead on Arrival», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Jackie Badger shook her head and half smiled at the sarcastic rant of fellow Googler Adam Stile. The geeks ran deep here, the brightest young minds in the world figuring out how to serve Internet users and make sure they stayed attuned to their screens. Some of the engineers were so geeky they redefined the concept. Adam fit the bill. If Google had a vote for most-likely-to-be-not-so-funny-as-he-thinks, he would win it.

Jackie set down her backpack in her cubicle and caught Denny’s eye. He was standing a few desks away in the vast cubicle den, clearly feeling the same way about Adam. Denny Watkins ran the department. Much more than that: he ran the Basement. That’s what Denny told Jackie he called it the first time he’d invited her down there, after several lunches and drinks. Just telling her about the Basement was an admission she’d been vetted. That she now knew.

Denny jerked his head to the side. She understood what it meant: Meet me downstairs .

Jackie sat at her desk and unzipped her backpack. She grabbed two clementines and put the tiny oranges next to a framed picture of her dog, Sadie. She reached into the backpack and started to pull out the big medical text. Then she thought better of it. Why bring any attention?

She felt a pang of frustration that the lecture had been canceled this morning. Now, they said, he was “on assignment.” There was a lot of speculation about what that meant, chatter in an online group of class members. He’s battling a seventy-foot microbe with just his stethoscope and flip-flops.

She knew better. Dr. Martin was heading to Tanzania. She’d overheard it through the doorway. Then she’d done a little harmless hacking to track his whereabouts. Greater good and all that. He’d said so himself when she’d asked about the ethics of disclosing the Saudi minister’s cause of death. She couldn’t wait for his next class and then his after-hours.

You’ve got a bright future. Clichéd, sure. But he even took time to single her out when he was fighting with that wretched dean. Jackie had risked putting herself out, asking him about patient privacy, and he’d perceived her as real, not as some showy kiss-ass med student trying to prove she was as smart as the teacher. She’d vacillated later whether she should’ve thanked him more clearly for what happened in Nepal and decided that would have come off as insincere. She’d rather be seen now as a full-bodied, able person than a self-doubting supplicant.

“I know when you’re this lost in thought we might have a patent coming,” said Denny, startling her. He was standing over her shoulder. “What gives, genius?”

“Wondering if we can patent your stealth gait. Who can walk that quietly?”

“You mean at two hundred thirty pounds?” Denny smiled jovially.

“Have a gluten-free bar.”

Nobody else would talk to Denny like that. Everyone in the department wondered about it—how Jackie talked so casually to the big Russian bear. It was hard not to see the warmth between them, less like friends or siblings, more like doting father and precocious daughter.

“How’s your audit class going? What is it again: remember-to-wash-your-hands 101?”

“It’s infectious disease…” Of course he knew. “Jackass.”

He laughed. “Can I talk with you about the protocol on that search tool?” he said.

It was thinly veiled code. Nothing specific. Just nonsense. When he said a nonsense sentence to her, it meant they were headed to the lab over at Google X. Sometimes, he said the most comically inane stuff, like Let’s optimize that engine, or Can I speak to you about the spreadsheet database? This time, Jackie could see from Denny’s eyes that, despite his innocuous code, he had something significant on his mind.

“Catch you in a bit,” Denny said.

Jackie snagged one of the shared bicycles outside Lemon-Lyme, the name of the three-story glass-plated building at Planet Google where she worked. It was hard not to feel a little excited by the prospect that they had some new data. For six months she’d been going over the same incremental reports on a handful of projects, one about Internet use habits, another about reaction times of Internet users. It was also hard for her not to feel a little used. Story of her life on some level: always with the extraordinary talent and often feeling like others were using it for their ends. It took a lot for her to trust the rare individual who now made it through her screening.

One such person was Denny. At Stanford, he plucked her from an engineering class where he’d lectured a single day, and, from the back of the room, she drilled him with a question that contorted his face into wonder and then laughter. After class, he beelined for her, took her to coffee at Peet’s, asked her to come work for Google. Less than a year later, he invited her to join on as a consultant for Project X, which was a catchall name for big, speculative ideas at Google that may or may not pan out, like the driverless car, clean water projects, interstellar communications technology. Her job, he told her, “was to use that overly developed antenna to ask the questions others don’t think about or are too haughty to ask.

“Jackie, I like you, but that’s beside the point. What’s important is that you see patterns other people don’t see. I’ll ignore the fact you’re not sure whether you like me.”

Jackie liked Denny’s candor and the fact that he seemed to put things in the right context. He was real. He always had food crumbs somewhere on his shirt or beard and he sometimes just stopped in the middle of a conversation and stood silently until he thought through what he wanted to say. He could live with taking his time, however awkward that might appear. It had taken her a long time to find someone she could invest in, and who she felt invested in her; three months after she joined Project X, Denny told her he trusted her enough to show her what was really going on. Not Project X, but the experiments in the Basement, the ones that didn’t get discussed in the media, or anywhere. Her confidence grew, and her willingness to insert herself, like in Dr. Martin’s class.

She rode her yellow bicycle off the campus sidewalk and onto the street. The move prompted her to glance in the rearview mirror, which is where she saw Adam Stile, the goofy punster from her engineering pod. He was seemingly riding in her path, following. When she glanced back, he put his head down. Then took a sharp right that landed him in a planter. Jackie, lost in the stupidity, nearly tipped over herself when slipping against a curb. She righted herself and accelerated. Something about Adam threw her off.

Or maybe, she thought, looking back, Adam, ever the gadfly, was following to see where she was going. But so what? It was no secret she worked with Denny at Project X. And there was no way Adam would get into the Project X building, let alone the lower offices. That would mean passing the human security upstairs, then taking the elevator using a key card and voice recognition protection to get to the floor, then the retinal scanner and the other stuff below that Denny said was “just best practices these days.”

Google, she often thought, was a multibillion-dollar labyrinth, an overflowing font of money, and power. And secrecy. It was insinuated in every facet of people’s lives, from work and driving, music, television, every form of communications. In the mazes of projects here, a collection of brilliant engineers who tinkered with, fine-tuned, intensified that power click by click.

She looked back. No sign of Adam. She pulled outside the Project X building and slipped the bike into an empty slot in the rack. She marveled at the line of electric cars in the lot. She had little doubt it forecast a future filled with battery-powered vehicles piloted by algorithms not humans. The line of cars reminded her of one of her prouder intellectual moments. Early on at Google, she’d suggested developing a program for Google Maps that entailed recommending driving routes to motorists that minimized the number of left turns and maximized right turns. It turns out that such a route can reduce global warming because drivers who take left turns have to wait before turning, thus burning more gas. On an individual basis, that is meaningless. In the aggregate, it adds up to tons of carbon emissions. Google eventually took up her idea, allowing drivers to opt for “eco” map mode.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Dead on Arrival»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Dead on Arrival» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Dead on Arrival» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.