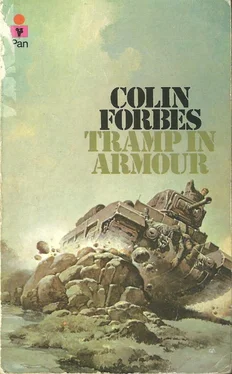

Колин Форбс - Tramp in Armour

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Колин Форбс - Tramp in Armour» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 1971, ISBN: 1971, Издательство: Pan Books, Жанр: Триллер, Историческая проза, prose_military, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Tramp in Armour

- Автор:

- Издательство:Pan Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1971

- Город:London

- ISBN:0-330-02686-0

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Tramp in Armour: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Tramp in Armour»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Tramp in Armour — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Tramp in Armour», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Yes, I remember.’ Storch hardly seemed to be listening. ‘I have just heard from Keller that this submerged road is not covered by the enemy – our patrol advanced halfway along it before dark without meeting any opposition. I’ve had the patrol pulled back to Lemont for the night.’

‘On the surface it does look promising,’ Meyer reluctantly agreed.

‘Actually, the road is under the surface.’ Storch flashed a confident smile and it made Mayer feel even more exhausted to see the general looking as though he had just risen from an excellent night’s sleep. ‘So the road to Dunkirk really is open, Meyer. Even allowing for a cautious passage by our tanks the advance forces will be inside Dunkirk two hours after dawn. And once we have Dunkirk the whole BEF is in our hands -over a quarter of a million men.’

‘But the message from GHQ…’ Meyer began.

‘I think we can deal with this. It’s badly garbled and the most recent order we received was quite clear – advance up the coast and seize the ports. That is what we shall do – we shall seize the last port. Dunkirk.’

‘I have asked the wireless operator to try and get through to obtain clarification.’

‘Then we shall have another confused reply which will make matters worse. Cancel the request for clarification.’

He waited while Meyer picked up the phone and gave the order, replacing the receiver reluctantly.

‘What is really worrying you, Meyer?’

‘I’m bothered about the huge concentration of ammunition at the dump. In this confined area inside the waterline…’

‘You have sufficient for the operation?’

‘Too much really…’

‘We can never have too much.’ He pulled his cap on firmly. ‘So we record the receipt of this latest message as being so garbled that it is meaningless. And now you can send off the confirmatory copy of my order to attack to Advanced Headquarters. We should be able to spare one staff car from our entry into Dunkirk. Send off the car within the hour.’

The colonel swallowed. Storch had now covered himself completely. By the time the staff car reached Advanced Headquarters the Panzers would be on the move along the partially submerged road.

‘Our rear, sir,’ Meyer persisted. ‘It is hardly protected at all, everything is facing north and east.’

‘Precisely! The British are in front of us, Meyer, not behind us. We advance at dawn as planned.’

The clock on Meyer’s desk registered 12.10 am.

Racing through the night, the transporter weaved steadily from one side of the road to the other and then back again as ^ Reynolds struggled desperately to prevent the German, truck from passing them. Again, the crisis had arisen with hardly any warning. Barnes checked his watch. 12.15 am.

Reynolds had warned them that headlights were coming up behind them very fast and that he thought it was another truckload of German soldiers. A sixth sense had told Barnes that it was highly unlikely that they would be able to repeat their previous deception and then he heard the horn blowing. The horn had gone on blowing ever since, and for a while the truck had been content to stay on their tail.

‘Sounds as though he’d like a word with us,’ said Colburn.

‘I’m sure he would,’ replied Barnes grimly.

‘I don’t see how they could have cottoned on to us.’

‘The road-block we smashed up. Someone must have sounded the alarm and sent this lot after us.’

Reynolds glanced in the rear-view mirror. ‘He’s going to try and pass us.’

‘Don’t let him.’

So Reynolds had started weaving the giant vehicle backwards and forwards across the road, blocking the track’s path each time it attempted to move up. Colburn had been surprised that they hadn’t opened fire, but Barnes had pointed out that behind the cab stood a tank with a 70-mm armour-plating and that the Germans must realize there was a tank aboard from the shape of the tarpaulin. They must also have realized that machine-pistol fire would scarcely scratch the plating, let alone penetrate the full length of the tank to reach the cab. And that, Barnes supposed, was why they were so anxious to pass – so that they could send a blast of bullets into the cab from the front. It couldn’t go on like this much longer, he was quite sure. They had to do something about that truck. He explained his plan briefly to them and then he opened the door and threw it back flat against the side of the transporter. The horn behind them was still blowing like a banshee. He went out backwards, holding on to the upper door frame while his right foot stepped inside the metal climbing rung. Looped over his shoulder, the machine-pistol didn’t help his balance and at the speed they were travelling the wind velocity buffeted bis body like a minor hurricane and tried to tear him away from his precarious grip. He stayed there for a second and wondered whether he was in full view of the truck, but the tarpaulin-shrouded tank was acting as a screen. Very carefully he sent his left foot out into space, feeling for the deck behind the cab. The foot felt nothing as the transporter lurched sideways and he nearly came off. There were too many things to cope with at once – keeping his grip, anticipating the violent swerves of the transporter, feeling around for the deck – and all the time the wind rush tore savagely at his body. This was worse, far worse, then he had expected. It was taking him all his time to hang on. Then his shoulder wound began to throb viciously and suddenly he felt dizzy and his head started to swim. That decided him. All or nothing. Gritting his teeth he made a supreme effort, lifting his left leg high, bringing it down where the deck should be. His foot hammered down on hard flat wood. He let go with his left hand and grabbed for die tarpaulin rope, praying that it was firmly attached to the rear of the cab. He pulled at the rope and when it held firm he let go with his right hand, his whole weight suspended from the rope now. At that moment the transporter swerved again and the violence of the momentum hurled him outwards.

His body described a complete arc of a hundred and eighty degrees, his left foot pivoting under him, his hand sliding down the rope, then his body slammed back against the tank with fearful impact and he ended up facing outwards, still clutching the rope with only his left hand as his right foot scrabbled for a hold on the deck. For several seconds he hung there helplessly, dazed with pain because when the swing of the arc had brought him round to crash backwards against the covered hull the first point of impact which took the shock was his wounded shoulder. Waves of dizziness trembled through his brain, a feeling of sickness welled up, and beyond it all the guns boomed, the horn shrieked, and the transporter swayed crazily from side to side. He was done for, he couldn’t summon up enough will-power to do anything but hang on. He fought down the sickness, tasted salty blood in his mouth where he had bitten through his lip, and then he felt Jacques grasp him, one hand round each upper arm. The grip steadied him while he grasped the rope with both hands, hauling himself in between the cab and the rear of the tank. Then, he flopped forward on the canvas over the engine covers and lay quite still, gulping in great breaths of air, desperately fighting for self-control as his wound screamed at him. He was vaguely aware that Jacques was lying beside him next to the turret. And all the time the vehicle swayed insidiously from side to side under him as he tried to push away the feeling that he was blacking out.

It was a terrible struggle to recover quickly, to get his choking breath back to normal, to push under the blinding waves of pain, but two things stimulated his recovery – the rush of fresh air and the insistent shrieking of the horn which continually alerted him of the imminent danger. Telling Jacques to keep flat he forced himself up on his knees, scooping up a ridge of tarpaulin to conceal his position. Then he extracted two spare magazines from his pockets, rested them behind the ridge and lowered himself flat, the machine-pistol next to his shoulder. Clubbing his fist he gave the agreed signal, banging three times on the rear of the cab.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Tramp in Armour»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Tramp in Armour» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Tramp in Armour» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Невилл Форбс - История Балкан [Болгария, Сербия, Греция, Румыния, Турция от становления государства до Первой мировой войны] [litres]](/books/390301/nevill-forbs-istoriya-balkan-bolgariya-serbiya-gre-thumb.webp)