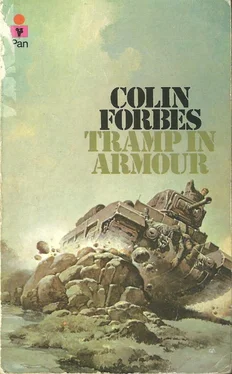

Colin Forbes

TRAMP IN ARMOUR

The war had started.

‘Advance right, driver. Advance right. Two-pounder, traverse left, traverse left. Steady…’

The tank commander, Sergeant Barnes, thought that should do the trick – when the tank emerged from the ramp on to the rail embankment, in full view of the German troops of General von Bock’s Army Group B, the turret would rest at an angle of ninety degrees to the forward movement of the vehicle, the two-pounder and the Besa machine gun aimed straight at the enemy. The tank crawled upwards at a steady five miles per hour, still invisible to the German wave advancing across open fields to assault the embankment behind which the British Expeditionary Force waited for them, while overhead the sun shone down on Belgium out of a clear blue sky, the prelude to the long endless summer of 1940.

Barnes’ squadron of tanks was positioned on the extreme right of the BEF line, and the troop of three tanks which formed his own unit was stationed on the extreme right of the squadron. Somewhere beyond this troop the French First Army, the next major formation which faced the attacking German army group, reached out its left flank to link up with the BEF, but this vital link was not apparent, which was why Barnes had just received his urgent wireless instruction from Lieutenant Parker, his troop commander.

‘Find out where the hell the French are, Barnes, and report back immediately, if not sooner.’

The natural route to the French, the road below the embankment, had been blocked by dive-bombers, and now what had once been a road was a barrier of wrecked buildings, so Barnes decided there was only one way to go – up to the top of the embankment and along the rail track in full view of the enemy. The prospect of exposing his tank like a silhouette on a target range didn’t greatly worry him: the armour on the upper side of the hull was seventy millimetres thick and none of the light weapons the German advance troops carried could do more than scratch the surface. As for the big stuff farther back, which was already lobbing shells into the BEF rear areas, well, he’d be off this embankment before they could bring down the range of their artillery. Any moment now, he told himself, pressing his eye to the periscope.

Four men crewed the tank: Trooper Reynolds inside his own separate driving compartment in the nose of the tank, while in the central fighting compartment Barnes shared the confined space with his gunner, Trooper Davis, and his loader-operator, Corporal Penn. The fighting compartment in the centre of the tank was shaped rather like a conning tower, the upper portion protruding above the tank’s hull; the floor, only a few feet above the ground, comprised a turntable suspended from the turret, so that when the power-traverse went into action the entire compartment rotated as a single unit, carrying round with it the guns and the three men inside, the traverse system controlled by the gunner at the commander’s instructions. They were very close to the top of the embankment now, but still the view through the periscope showed only the scrubby grass of the descending slope, while outside all hell was breaking loose, a hell of sound infinitely magnified inside the confines of the metal hull: the horrid crump of mortar bombs exploding, the scream of shells heading for the rear area, while the permanent accompaniment to this symphony of death was an endless crack of rifle shots, a steady rattle of machine-gun fire. It was only possible for the crew to hear Barnes’ sharp instructions because he gave them over the intercom, a one-way system of communication through the microphone hanging from his neck which transmitted the words to earphones clamped over the crew’s heads. Barnes screwed up his eyes, saw the wall of embankment disappear. They were over the top.

The view was much as he had expected, but there were many more of them – long lines of helmeted Germans in field grey advancing like the waves of a rising tide, running towards him across a vast field. Some carried rifles, some machine-pistols, and there were clusters with light machine guns. The tank had reached the embankment at the very moment when the first assault was being mounted.

‘Driver, straight down the railway – behind those loading sheds. Two-pounder. Six hundred.’ Davis set the range on his telescope. ‘Traverse left.’ With a hiss of air, turret and crew began to swing round, the tank still moving forward. ‘Traverse left.’ The turret screamed round faster, the guns and the fighting crew now at an angle of forty-five degrees to the tank hull. ‘Steady,’ Barnes warned, his gaze through the periscope fixed on the anti-tank gun hi the distance as a fusillade of bullets rattled on the armour-plate. ‘Anti-tank gun,’ he snapped, pinpointing the target.

‘Fire!’

Davis squeezed the trigger. The tank shuddered under the recoil, the turret was swamped with a stench of cordite. Barnes didn’t hear the explosion but he saw it – a burst of white smoke on the gun position, a brief eruption of the ground. Then they were moving behind the loading bays which the ramp served, out of sight of the enemy for swiftly passing seconds, emerging again as Barnes gave fresh orders.

‘Besa…’

The destroyed anti-tank gun was the only immediate menace to Bert, as they called their tank. Now for the German troops. The tank had scarcely moved beyond the sheltering wall of the loading bays when the Besa opened fire, the turret traversing in an arc from left to right, pouring out a murderous stream of bullets which cut down the first wave of Germans like a scythe. The turret began to swing in a second arc, the Besa elevated slightly to bring down the second wave, and all the time the tank moved forward down the rail track while Penn, who had already re-loaded the two-pounder, attended to his wireless. Parker, the troop commander, was speaking to Barnes now.

‘What’s the picture, Barnes?’

‘German assault waves just coming in – they’ll be over the top in your sector any second now. They stretch as far as I can see, sir. Over.’

He pressed the lever on his mike which controlled wireless communication and waited. Parker sounded exasperated.

‘But the French, Barnes – can you see the bloody French?’

‘Nothing so far, sir. I’ll report back shortly. Off.’

All the way up the ramp and along the embankment so far the turret lid had been closed down, so Barnes had relied on the periscope to let him know what was happening outside, a method of sighting which he found restricted and unsatisfactory. Now that he could no longer hear the clatter of bullets ricocheting harmlessly off the armour-plate, he risked it, pushing up the turret lid and lifting his head above the rim. For once, he was wearing his tin hat. A quick glance told him that no Germans were close to the section of the embankment they were advancing along. Instead, the troops in that area were running back across the field away from him: they had seen what had happened to their mates. To encourage their flight he gave orders to fire the two-pounder twice and then called for a burst from the Besa. If he was really going to see what was going on he would have to lift his head well out of the turret. He clambered up and stood erect, half his body above the rim, gazing all round quickly as he gave Reynolds instructions automatically.

‘Driver, full speed ahead down this railway. All the speed Bert will give.’

The tank began to pick up speed, one caterpillar track outside the railway, the other travelling midway between the two iron lines, while inside the driving compartment Reynolds had his eyes glued to the slit window in front, a window protected by four-inch armoured glass. Normally, he sat on his jacked-up seat with his head protruding clear of the hatch in the front hull, but now this seat was depressed so that he sat inside the hull and a steel hood was closed over the hatch above his head. He vaguely wondered what Barnes was going to do next, a line of thought which was occupying Barnes himself at the same moment.

Читать дальше

![Невилл Форбс - История Балкан [Болгария, Сербия, Греция, Румыния, Турция от становления государства до Первой мировой войны] [litres]](/books/390301/nevill-forbs-istoriya-balkan-bolgariya-serbiya-gre-thumb.webp)