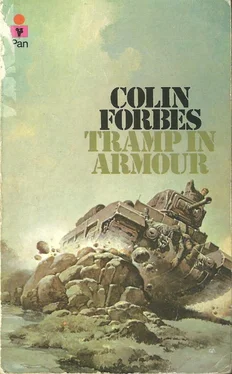

‘The fool’s dead. Just as well – we can’t afford to be lumbered with prisoners at this stage.’

‘He must have been stark raving bonkers.’

‘He’s a fanatic who thought he could get away with anything, but not completely bonkers. Take a look over your shoulder. I think Seft must have spotted them earlier than I did.’

A long way off to the south, where the road was now clearly visible in the early morning sunlight, Penn saw a thin trail of toy-like vehicles moving up the road towards them. The rear of the column was hidden behind a rise in the ground but more and more vehicles were appearing as the column advanced steadily forward. Barnes spoke grimly.

‘I’ll check with my glasses but that’s another Panzer column on the way, bet your life on it. So that route’s barred. And if we head back to so-called Fontaine we’ll run into the other lot.’

‘What the hell are we going to do? We’ll never get away with it a second time.’

‘Get out of here with Bert as fast as we can by the only route still open to us.’

At 4.30 AM they were fleeing for their lives. Moving at five miles an hour lie tank emerged from under the bridge and drove along the river bed between the high bramble-covered banks like a monster metal barge sailing downstream. Standing up in the turret, Barnes was enormously relieved to find that he couldn’t see over the tops of the banks which were two or three feet above his head, so that meant the enemy couldn’t see them either. As they left the bridge behind he looked back to make sure that the tracks weren’t leaving traces of their passage, but apart from a muddying of the water there were no traces to give them away. Ahead, the river ran almost straight for about a hundred yards and then it disappeared round a bend. They had to reach that bend and get round it before the advance elements of the Panzer column reached the bridge. He rated the chances of success a good deal less than fifty-fifty, but it was their only hope of survival.

About halfway from the bridge to the bend a line of trees covered the banks on both sides, their branches spanning the river to form a tunnel of foliage which roofed in the water below, and it was so dark inside the tunnel that he couldn’t see the river clearly. If it suddenly went deeper, they’d be finished anyway. Behind him the fording flap was closed down over the rear air outlets so now Bert was amphibious – amphibious, that was, in up to three foot six of water. He looked down at the grisly load roped on the back of the tank and hoped that they hadn’t left their departure too late.

Their departure from the bridge had been held up by the necessity of disposing of the two bodies – the sentry’s and Seft’s – and since he was determined to leave nothing near the bridge which might arouse suspicion and provoke a search, he decided that the only safe thing to do was to bring the bodies with them. The bodies were now lying, on the engine covers at the rear of the hull, attached to the turret by separate ropes.

The greatest danger was the motor-cycle patrols which he had seen through his glasses moving ahead of the column. They would follow the same procedure as the previous column, he felt sure of that. A patrol would arrive, halt to drop a sentry, and then drive on. The sentry would move on to the centre of the bridge and look straight down the river. Barnes looked down the river: yes, it was a good hundred yards to that bend. And there were other things to worry about. Driving a tank along the bed of a river, even a comparatively straight river, is not the easiest of manoeuvres, and he was constantly talking into the mike to guide Reynolds’ progress between the banks. They might just make it, so long as the river bed remained firm. From his elevated position he strained his eyes desperately to see the ground ahead under the water, searching for any sign of a large area of mud or softness or, worse still, a threat of rapids. And then there was "always the chance that the engine might stall, leaving them in full view of the approaching Germans. He put that thought out of his head quickly as Penn climbed up to join him.

‘Think we’ll make it?’ Penn asked him quietly.

‘If we can get round that bend in time.’

‘Can’t we get up a bit more speed – we’re crawling.’

‘Deliberately. This isn’t the Great North Road, you know, and I’m bothered about the river bed – it’s getting deeper.’

The water level was rising up the tracks quickly and he guessed the depth at over two feet. Three foot six was the maximum Bert could take. At the same time the river banks were closing in so that Reynolds barely had half a foot clearance on either side. The tracks ground forward, sloshing through the water, rattling over unseen rocks, grinding up mud discolouration, sinking deeper and deeper below the surface. Penn pulled a face as Barnes glanced back at the bridge.

‘Must be three feet at least now.’

‘All of that,’ Barnes said tightly.

They were halfway between the bridge and the tunnel of trees when a new anxiety assailed them – the sound of a plane. From the light-toned beat of the engine Barnes guessed that it was a small plane and it was flying very low. The Panzer column was using a spotter plane to check the ground ahead, which meant that the pilot would be searching every inch of countryside below him. If that plane flew over the river they were bound to be seen. Barnes could visualize it all clearly -the plane circling overhead while it wirelessed back to command HQ, the arrival of heavy tanks on both banks – in front, behind, above them. Then the remorseless shelling at point-blank range until Bert was reduced to a shattered hulk. It looked as though he’d taken them straight into a death-trap. He spoke into the mike.

‘Driver, increase speed by five miles an hour. Follow my instructions exactly. You’re too close to the left bank…’

The tunnel of trees still seemed a terribly long way off, and that tunnel could hide them from the plane if only they reached it in time. The sound of the plane’s engine was very close and it was flying lower. It had probably spotted the bridge and was coming in to reconnoitre the whole river area intensively. At that moment the tank almost collided with the right bank and Barnes corrected Reynolds sharply, which wasn’t fair because although the driver’s head was poked up through the hatch and he had a clear view ahead, his vision was limited at the sides and he couldn’t see the edges of the banks. The plane was losing even more height, Barnes could tell from the engine sound.

‘This is going to be dicey,’ Penn remarked.

‘Keep an eye on the bridge, will you? I want to concentrate on the sky from now on.’

He wanted to concentrate on several things – checking the sky, observing the bridge, watching the clearance on either side of the tank, and keeping a sharp eye on the river course ahead, but it was impossible. As usual, Reynolds was doing a marvellous job – any other driver would have stalled the engines, driven hard into the bank, committed any number of understandable errors, but Reynolds ploughed stolidly on… Barnes lurched sharply as the whole tank dropped, a really noticeable drop. Perm’s face went white and he quickly glanced down and then resumed observation of the still-deserted bridge. They must have dropped at least another foot and now they were semi-submerged under the river. The hull would soon be awash. Barnes grunted, checked the clearance on both sides, and scanned the sky. They’d have to gamble now, gamble on the desperate hope that the river stayed the same depth. That plane was almost on top of them – his hand tightened on the rim as he waited for it to flash into view. The tank rocked over an obstacle and his moist hand slipped. He , was recovering his balance, still looking up, when a roof of foliage blotted out the sky, a tangle of branches thickly covered with many layers of leaves. Above the green network the spotter plane sped across the river and continued on its course to the north.

Читать дальше

![Невилл Форбс - История Балкан [Болгария, Сербия, Греция, Румыния, Турция от становления государства до Первой мировой войны] [litres]](/books/390301/nevill-forbs-istoriya-balkan-bolgariya-serbiya-gre-thumb.webp)