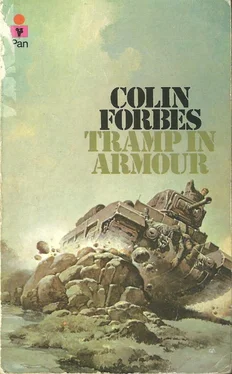

’Under the bridge?…’

But he was talking to himself. Barnes strode off-back to the road and scrambled down the bank by the side of the bridge, pushing his way through thick brambles to the river at the bottom. Yes, there was ample room under the high stone arch, but how deep was the river? Bert could comfortably wade through three feet of water provided the fording flap was closed over the rear air outlets. He found that under the bridge the water was less than a foot deep and blessed the fact that it hadn’t rained for over a fortnight. Even better, the bed of the river was surfaced with smooth rocks and between the rocks was a fine gravel.

An old footpath ran along the north side of the river, a footpath half-submerged under weeds and tall grass, and this would give them a place to sleep close to the tank. Looking up under the arch he judged that there was sufficient clearance to take Bert’s overall height of eight feet. Now for the question of concealment. He walked along the footpath under the bridge, pacing out the distance. Twenty-six feet. Bert’s overall length was eighteen feet so he would rest well inside the archway. The only problem lay in getting the tank down to the river bed – the banks were at least twelve feet high and steeply inclined, their slopes covered with a jungle of brambles and undergrowth. He went back to the tank and issued instructions, leaving Pierre by the roadside while he guided the vehicle some distance across a sun-baked field and well away from the bridge before they attempted the descent to the river bed: he was determined to leave no traces of their presence by smashing down undergrowth close to the bridge.

He checked the river depth again, returned to the tank, and ordered Reynolds to switch on the headlights, disliking the precaution but knowing that it was essential because it Was almost dark now below the level of the banks. Then the tracks began to descend, smashing down undergrowth, dropping with a bump as the tank’s centre of gravity pivoted on the brink and then plunged downwards, slithering and grinding over the brambles, hitting the water with a splash, the tank turning as Reynolds briefly halted the right track so that the revolutions of the left one swung the hull round through an angle of ninety degrees to face downstream. When Barnes shone his torch beam he saw that the river level was no more than a foot up the side of the tracks. As usual, Reynolds was handling the driving brilliantly even in this unusual environment. The tank advanced towards the bridge, a clearance from the banks on either side of several feet, moving forward over the firm river bed until they halted under the archway. Inside the hull Penn sat listening to the peaceful lapping of water round the tracks.

‘Now,’ said Barnes briskly, ‘time for supper. Penn, you take up temporary guard duty on the bridge while Reynolds brews up – I’ll come up and relieve you as soon as it’s ready. I wonder what the devil has happened to Pierre?’

He climbed down to the footpath and started to climb the bank when he heard Pierre coming along the footpath from upstream; the lad was carrying something in bis hands. When he switched on his torch he saw that Pierre was holding a large fish.

‘I caught it in a pool higher up – we can have it for our supper. There are many more – easily enough for one each.’

Penn paused, halfway up the bank on his way to the bridge. ‘What a marvellous idea – my mouth’s watering already. Pity we haven’t some chips to go with them.’

‘Give it to me!’ Reynolds thrust an eager hand forward and Barnes remembered that the driver had been a fishmonger before he had signed on. ‘I’ll start cleaning it as soon as I get the brew-up going.’

‘You really want raw fish for supper?’ Barnes asked quietly.

‘Raw?’ Penn protested. ‘We can cook the damned thing in no time.’

‘There’ll be no cooking here tonight. It’s a warm evening, the air’s absolutely still, and a cooking smell could linger round this bridge for hours. I’m not risking it. We’ll have to make do with tea and bully beef. We’ve got the French bread Pierre brought, too,’ he added.

‘For Christ’s sake!’ exploded Penn.

‘You’re supposed to be up on that bridge keeping a lookout,’ replied Barnes with deceptive calm.

‘Sorry,’ Penn spoke stiffly, turned away, and clambered up to the top of the slope.

Reynolds said nothing and went back to preparing a brew-up on his little stove. Barnes waited for the Belgian lad’s reaction with interest. Putting his hands back behind his head, Pierre hurled the fish as far as he could downstream and sat down on the footpath, not looking at Barnes. Under the archway, Reynolds worked in silence, unpacking his spirit stove, inserting white metaldehyde tablets, applying a lighted match, and then replacing the metal cap over the flame. When he went off upstream to fill his kettle he was gone for several minutes and Barnes guessed that he had taken water from Pierre’s pool so he could look at the fish.

The stove was not standard issue, but many of the items they carried, such as their sheath_knives, had never appeared on any official list of equipment: Barnes had long ago decided that his tank must be able to operate as a self-contained unit without the normal supply facilities when necessary, although never in his wildest theorizing could he have visualized a situation like this where they would find themselves behind the enemy lines, cut off from all contact with their own army, let alone their own troop. I took the right decision, he told himself as he thought of Penn’s irritability and watched Reynolds’ abnormally slow movements in preparing the supper. Those two haven’t enjoyed more than four hours’ sleep a night since we landed at Fontaine and today was no picnic. Until we get some rest none of us is capable of taking part in action against the enemy, so the only thing to do is to keep our heads down until we’ve recovered. I hope to God we get a peaceful night. He went up to the bridge to relieve Perm.

Too tired to talk, they ate in silence by the light of the nickering spirit stove -Pierre, Penn, and Reynolds sitting side by side along the pathway under the arch while the water gurgled past the tank’s tracks. It was quite dark now and in the pale blue flame the tank looked enormous and strange, as though it stood in some war museum. Penn clapped a hand on the back of his neck and swore: it was after ten o’clock but the air was warm and muggy and the mosquitoes were active. He could hear one buzzing close to his ear and the blighter wouldn’t go away. He hurried his meal, because until he had finished, Barnes, who was standing guard on the bridge, would have to go hungry. Now that he had got used to the idea, Penn rather liked the feeling of security of being tucked away under the bridge: it was like camping out in a cave, something he’d always enjoyed as a boy. He must remember to change Barnes’ dressing and he’d insist on taking first guard duty on the bridge. It would make up for some of his grumbling during the day.

Half an hour later he had changed the dressing and had gone up to the bridge to mount guard. Barnes was sitting on the footpath as he put on his jacket again, thankful that the emergency dressing had been applied and feeling sufficiently better to appreciate his own state of incredible fatigue, but at least he felt more comfortable. As he dressed himself he looked sideways at Pierre. He had been conscious of the lad’s fixed stare for several minutes.

‘We may find somewhere to drop you off tomorrow,’ he told him.

‘That is for you to decide.’

‘Yes, it is, isn’t it? You’d better get some sleep now. We may have a long day ahead of us.’

‘Can I take my share of guarding the bridge, Sergeant?’

Читать дальше

![Невилл Форбс - История Балкан [Болгария, Сербия, Греция, Румыния, Турция от становления государства до Первой мировой войны] [litres]](/books/390301/nevill-forbs-istoriya-balkan-bolgariya-serbiya-gre-thumb.webp)