James Patterson

Target: Alex Cross

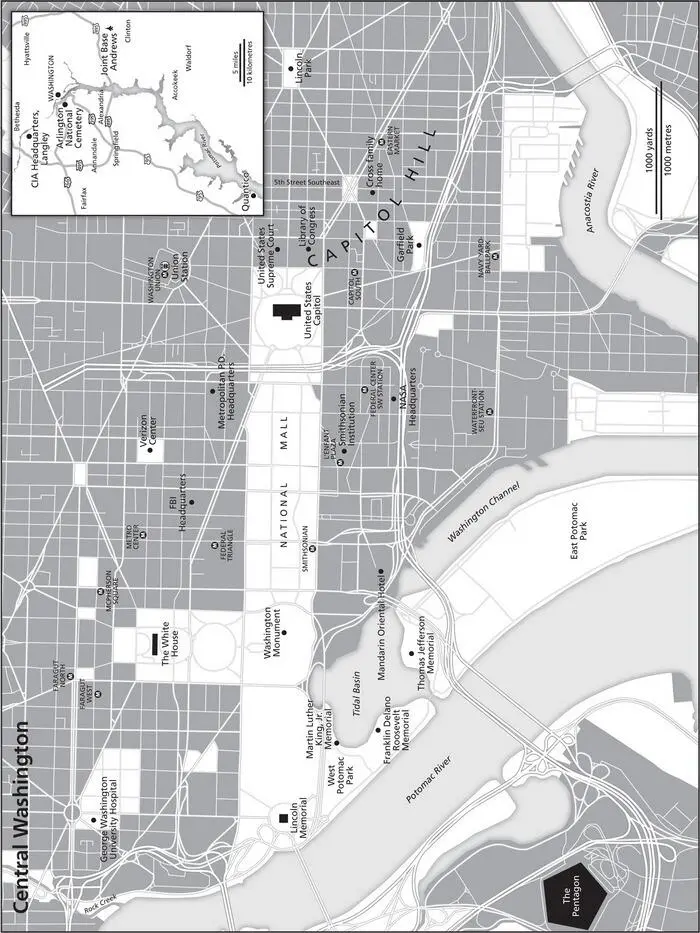

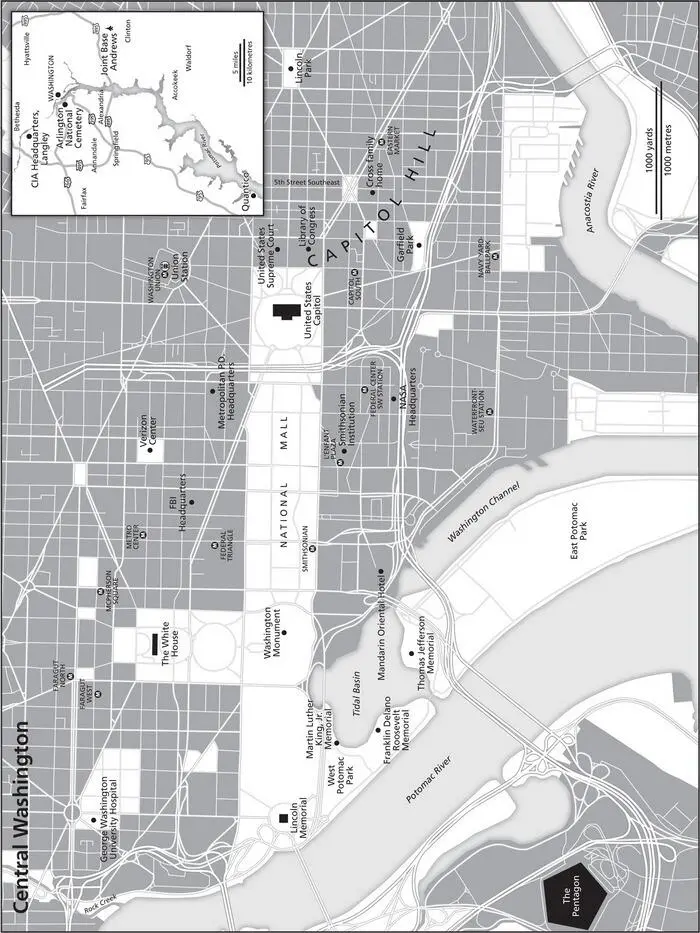

Temperatures that late January morning plunged to four degrees above zero, and still people came by the hundreds of thousands, packing both sides of the procession route from Capitol Hill to the White House.

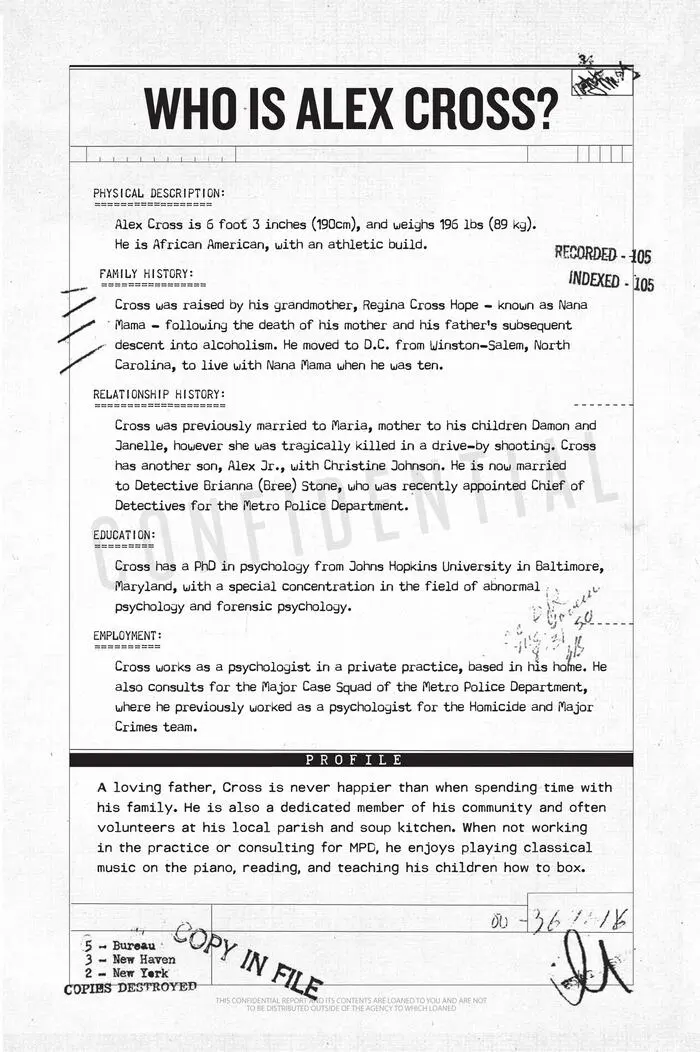

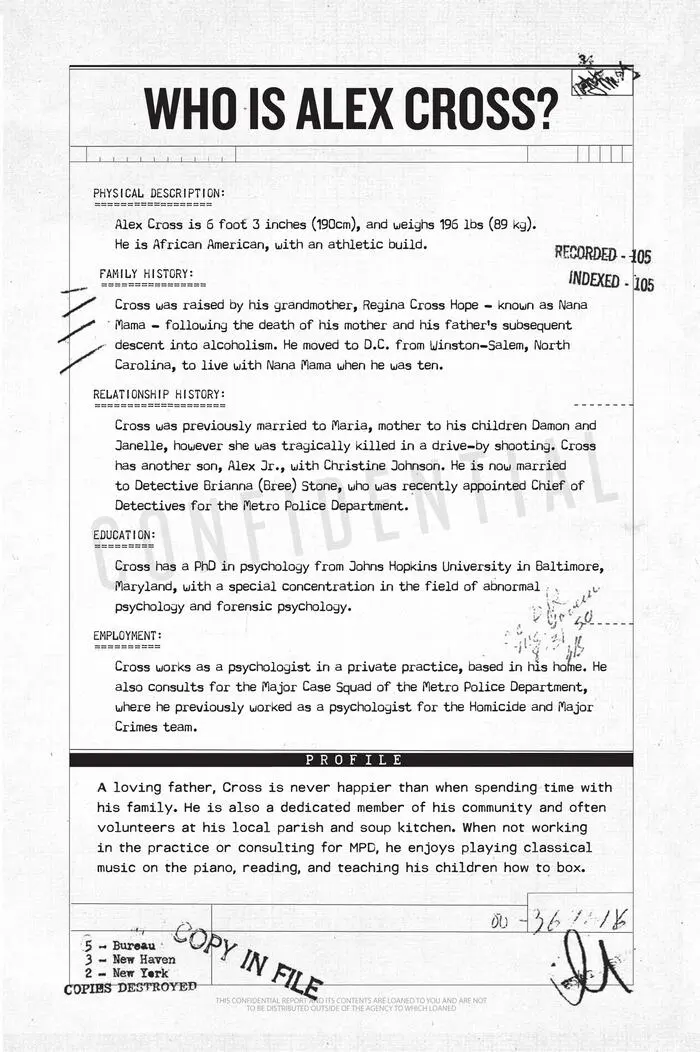

I was waiting at the corner of Constitution and Louisiana Avenues surrounded by my entire family. Bree Stone, my wife and DC Metro PD’s chief of detectives, stood in front of me wearing her finest dress blues.

My twenty-year-old son, Damon, was on my right. He had flown up from North Carolina the night before and had on long underwear, a suit and tie, and a black down jacket. Nana Mama, my ninety-something grandmother, had refused to listen to reason and watch this on TV. Sitting in a folding camp chair to my left and wrapped in blankets, she wore a wool ski cap and everything warm she owned. Jannie, my seventeen-year-old, and Ali, nine, were dressed for the Arctic but hugging each other for warmth and stamping their feet behind us.

“How much longer, Dad?” Ali asked. “I can’t feel my toes.”

Over the soft din of the crowd and from well up Capitol Hill, I heard the four drum ruffles and bugle flourishes that precede “Hail to the Chief.”

“They’re leaving the Capitol,” I said. “It won’t be long now.”

The presidential anthem soon ended, and the cold crowd quieted.

I heard a man’s voice call out, “Right shoulder, arms!”

Another voice repeated the call. And then a third. One by one, every fifty yards and moving east to west, the soldiers flanking the route followed the command, bringing their rifles to their right shoulders and standing at ramrod attention.

The drums began to beat then, the slow cadence sounding muffled and somber from that distance.

One hundred West Point cadets appeared at the top of Capitol Hill, all dressed in gray and marching in unison. Similar contingents from the U.S. Naval, Air Force, and Coast Guard Academies followed, striding in precision, heads high, eyes focused straight ahead as they reached the bottom of the hill and passed us.

Up on the hill, the slow, steady beat of the drums continued, getting louder and coming closer. A color guard appeared bearing flags.

I heard the clopping of hooves before seven pale gray horses trotted from the Capitol grounds. Six of the horses moved in formation, two following two following two. The seventh horse marched at the head of the column to their left.

All seven horses were saddled, but only the left-hand three and the horse at the head of the column carried riders, uniformed members of the U.S. Army’s Old Guard unit. The six horses in formation pulled the hundred-year-old black caisson that bore the flag-draped coffin of the late president of the United States.

The slow, steady clip-clopping of the horses came closer and closer, the noise building along with the somber beat of the drum corps.

Behind the caisson, a black, riderless horse, known as a caparisoned steed, shook its head and danced against the reins held by another member of the Old Guard.

The late president’s personal riding boots were turned backward in the stirrups.

“Why do they do that?” Ali asked in a soft voice.

“It’s a military tradition that signifies the fallen commander,” Nana whispered. “They did the same thing at President Kennedy’s funeral almost sixty years ago.”

“Were you here then?”

“Right where you’re standing, darling,” Nana said, wiping her eyes with a handkerchief. “I remember it like it was yesterday, just as tragic as today.”

I wasn’t alive when JFK was president, but Nana had told me that it had been a time of great hope in the country because of its young leader and that hearing of his assassination had felt like a kick in the gut.

I’d felt the same way when Bree called me to say that Catherine Grant had collapsed in the Oval Office and died at age forty-seven, leaving behind a husband, twin ten-year-old daughters, and a stunned and grieving nation.

President Grant had been among the rarest of creatures in American politics, someone who actually managed to bring opposing sides together for the benefit of the country, and she’d done it by sheer force of her empathetic personality, her piercing brilliance, and her self-deprecating wit.

A former U.S. senator from Texas, Grant had won the White House in a landslide, and there’d been a real feeling of optimism in the country, a belief that the gridlock had ended, that politicians on both sides of the aisle were finally going to put their differences aside and work for the common good.

And they had, for three hundred and sixty-eight days.

Seventy-two hours after celebrating her first year in office, President Grant had been meeting with her military advisers when she suddenly complained of dizziness and seemed confused, then fell to the floor behind her desk. She died within moments.

Her doctors were stunned. The late president had been in top physical condition, and she had passed a rigorous physical exam with flying colors not two months before.

But the pathologists at Bethesda Naval Hospital said that Grant had succumbed to a fast-growing tumor that had enveloped her internal carotid artery, essentially interrupting the blood flow to most of her brain. No one could have saved her.

So there was a real sense of shared loss and broken hope the morning of her funeral. As her cortege approached us, the mourners on both sides of Constitution Avenue turned sadly quiet.

Damon helped Nana Mama to her feet. Bree and I came to attention, and I had to fight against the emotion that built in my throat as Grant’s coffin rolled by and the black riderless horse pranced and reared in the bitter-cold air.

But what really hit me was the sight of the limousine that trailed the black horse. I couldn’t see them, but I knew that the late president’s husband and daughters were inside.

I remembered how I’d felt when my first wife died tragically, leaving me lost, angry, and alone with a baby boy to care for. Those were the worst days of my life, when I thought I’d never be right again.

My heart broke for the First Family as they passed. I blinked back tears watching the drum corps march by, eyes straight ahead, the cadence of the funeral beat never wavering.

“Can we go now?” Ali asked. “I can’t feel my knees.”

“Not before we all hold hands and say a prayer for our country and that good woman’s soul,” Nana Mama said, and she held her mittened hands out to us.

Snow fell as Sean Lawlor slipped into a narrow alley in Georgetown. A ruddy-skinned man with a salt-and-pepper beard and unruly hair, Lawlor was dressed in dark clothes, gloves, and a snap-brim cap with the earflaps down. As he moved deeper into the alley, he knew he was leaving tracks in the snow but didn’t care.

Forecasts were calling for six inches before dawn, and he planned to be finished and gone long before the storm ended.

Lawlor padded to the rear gate of a beautiful old brick town house that faced Thirty-Fifth Street. After a long, slow look around, he climbed the gate and crossed a small terrace to a door he’d picked earlier in the evening after bypassing the alarm system.

It was four fifteen in the morning. He had half an hour at most.

Читать дальше