Back then, Luke could tell Gillian cared about her appearance. Her smooth shoulder-length bob was almost black, and she always wore make-up; her mascara never streaked with her tears. Perhaps that was a distraction for her – a mask she wore in public. But now her hair is lighter, pulled into a scruffy bun at the base of her neck, and her face is free of make-up. She’s thinner now – almost too thin.

He follows Gillian into the kitchen. The floor is white, the cabinet doors are white, and the massive island in the middle is topped with white marble. Everything is spotless, gleaming.

‘Can I get you anything to drink?’

Luke’s tempted to ask for a shot of that vodka he spots in the drinks cabinet.

‘Black coffee, no sugar, please,’ he says.

She raises her eyebrows.

‘I had you down as a builder’s tea, three sugars kind of man.’

‘I was last week.’

She flicks on the kettle and gestures for Luke to sit at one of the bar stools. He tries to mount it as gracefully as he can, but his hands are full with his leather satchel and mobile phone. Gillian has the courtesy to turn away as he places everything on to the marble top before sitting.

His questions are listed on a notepad and a recording app is ready to go on his phone. Gillian places the steaming coffee in front of him. He’ll have to wait at least five minutes before he can attempt a sip – she hasn’t topped it up with cold water. But he’s not in a café; that’s another of Helen’s phrases.

Gillian sits at a ninety-degree angle from Luke, a herbal tea in a glass cup in front of her. There are bags under her eyes that seem to threaten tears at any moment.

He’s about to ask the first question when his stomach growls. The room is so quiet that she must’ve heard it.

‘Did you miss breakfast?’ she says. ‘You reporters must be so busy. Would you like a biscuit?’

She’s talking as though she’s his mum. It must be terrible for her, being a mother when her only child is dead. Luke banishes the notion from his head.

‘I had breakfast, thanks. It was a smoothie.’

Shit, why is he being so unprofessional today? Luke’s usually so together, but he feels edgy around her. He can’t imagine losing one of his daughters, especially in that way. It’s like he’s too close to the tragedy and that just being part of it will harm his own family.

God. Stop it. He can’t think like that. How bloody disrespectful.

Luke picks up a pen and taps the pin code into his phone.

‘Are you OK to start?’

She nods, slowly, wiping a strand of hair from her face. Her shoulders are straight; she’s so composed, given the circumstances.

‘How do you feel about the imminent release of Craig Wright and his intention to come back to the area?’

‘Straight to the point as usual, Luke.’ She picks up her glass cup and sips the tea, a slight shake to her hands. ‘As you know, my husband has never done interviews… didn’t want to read Lucy’s name alongside that man’s. He says he’d kill Craig if he ever saw him in the street. Brian agrees with me… that Craig coming back shouldn’t be allowed. Life should mean life – that’s what people say all the time, isn’t it?

‘Why drag everything back up again?’ She rests her elbows on the counter and leans towards Luke. ‘What he did in the first place was evil enough.’ She reaches a hand out and places it near Luke’s mug. ‘Please don’t refer to my husband in the article.’

‘I won’t.’

‘Good,’ she says, sitting up straight again. ‘Most of them don’t care about our feelings when they’ve written about Lucy. You’re the only one who’s kept to your word. It’s why I agreed to this interview. I’m not going to speak to any other newspaper.’

‘I appreciate that.’

‘I bet you do.’ A brief smile crosses her face before she frowns. ‘Anyone who’s committed crimes like that shouldn’t be allowed back into any community. What he did to my daughter and Jenna Threlfall was… inhuman – not that he was ever convicted for Jenna. What must her family be going through?’

‘We can’t write about Jenna in connection with Craig, unfortunately.’

She doesn’t register Luke’s words.

‘And he confessed near the end… The trial had nearly finished! What sort of person does that? He was thinking about himself, to get a reduced sentence. Did he want the world to hear about what he’d done? Have my child’s image shown to a room full of strangers?’

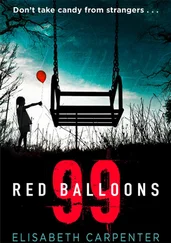

Luke sees them in his mind as clear as the first time – he wishes he couldn’t. Lucy’s burgundy T-shirt pushed up around her neck, her face white, lips blue, eyes wide open. A single straight open wound on her abdomen – her intestines tumbling out after small animals had begun to eat her, inside out.

Gillian gets up from the stool and plucks several tissues from a box on the counter. She turns away from Luke as she dabs at her face and blows her nose.

‘I’m sorry about that,’ she says, sitting back at the island. ‘I never know when it’ll hit me. I could be sat in traffic, see one of her friends pushing a pram, or on their way to work, and it’ll overwhelm me. Lucy never had any of that. She’d barely turned eighteen. She will always be eighteen. If it’d been a month before, she’d have been classed as a child… Craig would never be released.’

Lucy seems such a young person’s name, he thinks. Would she still’ve suited it if she’d had the chance to grow older?

‘Would you like to take a break?’ Luke says.

‘A break?’ She gives a bitter laugh. ‘I never get a break from this. It makes some people uncomfortable when I cry… even my own father. He thinks I should be over it by now.’ She covers her face with her hands for several moments, her shoulders rising as she takes a deep breath. ‘He’s always been so cold, especially when I was a girl. How can anyone get over losing a child?’

‘I don’t know.’

Luke feels pathetic, helpless. He hates his job sometimes. What’s the point of it all if you can’t change anything? All he does is tell readers about events after they’ve happened. Helen says it’s important, that people have the right to know what’s going on in the world. She wouldn’t feel the same way if it were her own life being read about by thousands.

‘Did Lucy know Jenna Threlfall?’ says Luke. He’s probably asked the question before, but there’s nothing about it in his old notes.

‘Vaguely,’ says Gillian. ‘They went to the same school, same college, but they didn’t spend much time with each other. I’d never met her – didn’t know she existed until…’

‘But they could’ve spent time together at college and you might not have known about it?’

‘I suppose so.’

‘It’s just too much of a coincidence that they went to the same place and were both—’

He stops himself, knowing he’s pondering aloud to one of the victims’ mothers.

‘I know,’ says Gillian. ‘The police would’ve looked into it at the time, though, wouldn’t they?’

After a few minutes’ silence, Luke says, ‘Have you ever thought of moving away, like Jenna’s parents did?’

Her mouth falls open; she leans back, and Luke worries she might topple from the stool.

‘Why should I leave?’ she says, raising her voice for the first time. ‘Lucy’s room’s upstairs. How could I get rid of that? She’s still my daughter. I’m still a mother. She’s with me every single day, I can feel her. Where would she go if I weren’t here? Don’t look at me like that, Luke. I haven’t lost my mind. But when you lose a child, you have to believe there’s something else after this. Otherwise, I couldn’t carry on living. I want to do her proud… live my life for her because she can’t. She was passionate about so many things. I volunteer in several of the places she did… I’m not going to list them now because I think it should be private. Can you believe an eighteen-year-old volunteered in her spare time? It was like she—’

Читать дальше