We hug for a few seconds. I’d love to hold him for longer, but this is all we’re allowed.

‘Hello, Mother,’ he says, as usual, pulling away from me. His northern accent’s stronger in here than it ever was at home.

‘Hello, Son.’

I sit on the plastic chair and shuffle it towards the table that divides us. He used to be such a skinny child – he was slim, even as a teenager. He took up weight-training after the first few years in here, said he didn’t want to be a victim any more. Looking at him now, it’s like he’s doubled in size. That grey sweatshirt used to drown him.

‘There was a documentary on last Friday,’ he says, ‘about penguins on the Falkland Islands. Did you see it? I thought of you when I watched it. I said to myself, Mum’ll be watching this, she likes —’

‘No,’ I say. ‘I didn’t, sorry.’

‘But it was only on at seven.’

‘I don’t sit and watch television all day,’ I say sharply.

I must’ve fallen asleep. I don’t sleep well. Unless I’m doing the shopping, I’d rather sleep during the day. Then at night I can go out into the backyard and breathe in the fresh air.

Out of the window to my right, there’s just the right amount of sky and trees visible to remember there’s a world out there.

‘What’s wrong?’

‘Nothing,’ I say. I look at him as he stares down at his hands – his nails are bitten so badly; the tops of his fingers are smooth and shiny. I glance at his face; such lovely long eyelashes. ‘I’m sorry if I was short with you.’

‘Has everyone heard?’ he says. ‘Are they giving you a hard time again?’

A hard time . He makes it seem like a cross word or a quarrel over parking spaces.

‘No,’ I say. ‘But I’m worried about you… about what’ll happen in a fortnight. We could move away, you know. Start afresh. I’ve always fancied the Lake District.’

‘How the hell would we afford the Lake District? You’re dreaming again, Mum.’

It’s all I have, I want to say.

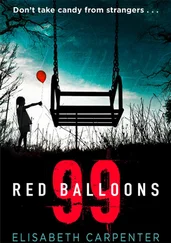

‘I know I’ve asked this nearly every time you’ve visited,’ he says, ‘but I thought I’d ask one more time. For tradition, I suppose. One last time. Have you found him?’

‘No. No, I haven’t.’

His shoulders drop, and he lowers his head.

He means Pete Lawton. The man Craig has always said he was with the night Lucy was murdered. There’s been no sign of him since, and I can’t find anyone that’ll vouch for him working at the garage when Craig was doing work experience there.

‘Anyway. About your bedroom…’ I say, trying to distract him. ‘I hope you don’t mind, but I put some of your old things in boxes – only your boyish things… didn’t think you’d want to be looking at them. I’ve not thrown them out – they’re in the loft.’

He smiles slightly.

‘I can’t wait to be home, Mum. It’ll be like old times.’

I give a small smile. I don’t want to mention that the old times meant he was never home, barely giving me the time of day.

‘Have you had a visit from probation yet?’ he says.

‘Yes, but they’re coming again tomorrow.’

‘I told them I want to be a personal trainer.’

‘Oh,’ I say. ‘What did they make of that?’

He tilts his head and shrugs.

‘They said it’s not likely… I’d need one of those background check things. But what do they know?’

‘I suppose,’ I say. ‘If you put your mind to it, you could do anything.’

My words hang in the air like a moth hovering before a bare flame.

‘I want to make a life for myself.’ His knees bounce up and down underneath the table. ‘If it doesn’t work out, I promise we’ll move. How about that?’

I stretch my fingers as close as I can towards his and he does the same back.

‘I’ll help you all I can, love.’

I know he doesn’t mean what he says. He’ll not want to be living with me for long – seventeen years is a long time to be trapped inside. He’ll want to see some life.

Too soon, it’s time to go. He quickly lists the items he wants me to buy. I’m not sure if it’s allowed, him having two phones, but I tell him I’ll get them anyway.

‘I love you, Son,’ I say.

‘Right back atcha, Mum,’ he says, as usual.

I stand. I’m leaving this prison for the last time. Inside this place, he’s safe, he’s warm, he’s fed. He doesn’t know what he’s coming home to, does he? Everyone thinks he’s guilty; they’ll probably think he’s got a nerve returning to the town where it happened. They’ll be angry, I know they will.

And I don’t have the power to protect him from it.

Luke

Luke Simmons sits too heavily on his chair and it wheels visibly backwards. The work experience lad next to him purses his lips, suppressing a snigger probably, which is rare for one of these millennials; they usually feel the need to share bloody everything. They’ll be comparing shits on Snapchat soon, given a few months.

God. How has Luke’s belly got so big that he can’t even sit on a chair without sounding as though he’s been winded? It’s not as if there’s much fat on the rest of him. It’s his wife Helen’s fault. She’s been on a diet of only five points a day or whatever, and the mere idea of zero-point crap soup makes Luke crave his mum’s proper chip-pan chips from when he was a lad.

He sniffs the air. The Greggs cheese and onion pasty that’s been keeping his left nipple warm in his jacket pocket smells like BO. Great. Overweight, and now everyone within five feet of him reckons he’s a soap dodger.

Ah sod it , he thinks, taking it out and pushing the pasty up from its paper bag. He can taste every glorious calorie and it warms his soul. Oh, how I’ve missed you , he says in his mind. It’s been a long week – thank God it’s Friday tomorrow.

Afterwards, he immediately feels that he shouldn’t have eaten it. He can feel the cholesterol coat his arteries and the fat adding another layer to his abdomen. ‘It’s for the kids,’ Helen said on Sunday as she was chopping celery and carrots into batons. ‘We’re older parents – we’re not far off forty. We need to think about them .’ Yes. Luke should’ve thought about them. He’d read enough crap editorial copy to know that eating pastry wasn’t the key to eternal youth.

It’s just too hard to resist. It’s a well-known fact that life’s shit these days. Baby boomers and happy-clappy hippies are what his parents were. What do we have now? Brexit and Donald Trump. And it’s pissing it down outside. Luke rests his chin in his hand.

‘Luke!’

It’s Sarah, the news editor – who’s also his line manager, head of PR and something else. When had it all got so corporate? It used to be more about the story. But that was when this place was bigger, had more staff and more actual paper copies were sold. Luke sits up, grabbing a pen from the pile on his desk.

‘Sarah!’ he says. ‘Light of my professional life.’

She frowns.

‘Are you trying to be funny?’ She leans towards him. ‘You know there’s a fine line.’

‘I… No. I was only trying to lift the mood.’

‘What mood?’

‘Sorry, Sarah. I don’t know.’

Luke lowers his head a little. He doesn’t know what to say any more. Back in the day, everyone joked with each other. Now there’s HR, PR, HSE, and God knows what else.

‘Craig Wright is out in less than a week,’ Sarah says.

‘I know – I’m putting a piece together. I’m going to contact his mother, see if she’ll talk to me again… find out if she still believes he’s innocent after all this time.’

‘Good idea. Plus, he’s planning on moving back to the area. Thought we should warn the community in a roundabout kind of way.’

Читать дальше