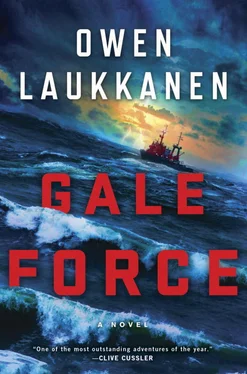

She slammed the radio handset back into its cradle. Stared out at the Lion , now visibly rocking as the waves crashed against her hull.

“Well, we can’t just sit around and wait,” Court Harrington said. “I need to get aboard before this weather turns nasty.”

At the Lion ’s stern, the Salvation bobbed, no sign of life from the afterdeck or the wheelhouse. McKenna studied the smaller vessel, felt Harrington’s eyes on her, knew he was growing impatient, probably doubting her ability to bump Christer Magnusson out of the way.

If your dad was here—

Shut up . McKenna reached for the radio. “Hell, no, we’re not waiting,” she told Court. “Hello, Munro ,” she said into the handset. “This is the Gale Force . I’d like to talk to your commanding officer, please.”

• • •

THE MUNRO ’S CAPTAIN WAS A MAN named Tom Geoffries. He listened as McKenna laid out her argument. But McKenna couldn’t convince him.

“The Salvation assures me they have the situation under control,” Geoffries told her. “Frankly, Captain, this sounds like a load of sour grapes from an outfit who gambled and lost.”

McKenna gritted her teeth. “I appreciate how it might sound that way, Captain Geoffries,” she replied. “From my angle, I have a high-horsepower, deep-sea tug stocked with the best salvage experts, divers, and naval architects in the business, and none of us can do our jobs because a group of pretenders are standing in our way.”

Geoffries came back harsh. “I think you’re out of line, Captain Rhodes.”

“Sir, you know as well as I do that this weather is only going to get worse,” McKenna said. “That ship’s rate of drift is going to increase, and assuming she doesn’t sink, she’s going to hit land sooner or later. And I’m telling you, in this gale we’ve got coming, that little navy tender over there isn’t going to be anything more than a speed bump.”

Geoffries didn’t respond. McKenna waited. If the Coast Guard captain cut her out, the Gale Force would have no choice but to stand down, watch the Lion drift toward land, and pray there was still time to act when the call finally came.

The radio crackled. “I’m sorry, Captain Rhodes,” Geoffries said at last. “Until they prove they’re not up to it, this is Commodore’s wreck. I just can’t break their contract without cause.”

This was a nightmare zone.

Okura dangled in darkness, lowering himself slowly down a line of rope, his feet pressed tight to the deck as he walked himself backward, searching the long line of Nissans for the briefcase. The cars hung around him, rocking with the ship’s motion. They reminded Okura of an uncut sheet of dollar bills, one single unit moving in unison, rising and falling and rising again.

The weather outside must have worsened considerably. The creaks and moans had become more pronounced, the sway of the ship heavier. A couple times, Okura was thrust up and away from the deck with the force of the swell, tossed into the air and then down again, his grip on the rope slipping, his feet nearly giving out.

Somewhere below him was water. Okura could hear it sloshing in the darkness, something dripping. The decks were slick with oil. It leaked from the cars’ engines and drained steadily down the listing deck. Okura imagined the dark frothy mixture at the bottom of the cargo hold, imagined falling into the cold water, drowning in it, coughing up oil and freezing salt water in pitch-black surroundings.

Somewhere below, too, was Tomio Ishimaru. Okura had wrestled the stowaway’s body off of its little platform, sent it plunging down to the darkness, heard it collide with something, a car probably, then another. Then he’d heard the splash, and the stowaway was gone.

Fifty million dollars . Now it’s all mine.

• • •

THERE WAS STILL NO SIGN of the briefcase when he’d reached the end of his rope. Okura wrapped it around his glove, found another bulkhead wall to rest against, then stretched and drank water from the canteen he’d stuffed in his pack. Surveyed the situation.

There were cars everywhere. The darkness seemed to close in around them, bringing with them a lingering, primal fear. This was a madhouse.

Three or four rows down, Okura could see the portside hull of the Lion . There was a pool of oily water immersing the first row of cars completely, and part of the second row. Headlights emerged from the murky depths like shipwrecks. There was still no sign of the briefcase.

It must have fallen all the way to the bottom, was probably lying somewhere in that oily water. Okura hoped the briefcase was watertight, imagined coming all this way to find a case of sodden, pulpy stock certificates, unreadable and utterly useless, the perfect punch line to this entire sick joke.

The rope was too short to continue any farther. Okura suddenly felt exhausted, beaten, and he wondered how many hours he’d spent down here, whether it was still daylight outside.

Magnusson will salvage this ship, he thought, staring down the row of cars toward the icy water at the bottom. He’ll pump out all the water and bring the ship upright, and I’ll intercept the briefcase when the ship has been saved. To hell with staying down here any longer.

He stood and straightened, already feeling the fresh air on his face, tasting the hot food in the Salvation ’s galley. But as he turned toward the hatchway and prepared to make the climb, he spied something, a blur as his headlamp passed over it, and then he looked closer and saw it was the briefcase.

It was lying on the windshield of a sports sedan, five or six rows away. Only God could tell how Ishimaru had managed to kick the damn thing so far, but there it lay, dry and unmolested.

Now all that remained was to retrieve it.

By morning, the gale was a foregone conclusion.

The waves had grown to ten-foot swells overnight, gloomy gray rollers that rocked the Gale Force fore and aft, coating her decks with salt spray, spilling coffee and ruining sleep. McKenna and Al Parent traded off all night, jogging the tug in the swell, keeping her bow pointed to the waves. McKenna watched the Lion , searching for any sign that she was flooding. Waiting for the moment the big ship finally sank.

Morning was a gray horizon to match the sea, the Lion drifting north at a knot and a half an hour, the Salvation ’s efforts to arrest the drift not amounting to much. The wind was gusting to twenty-five, the gale warning all over the forecast. It would arrive in earnest by afternoon, and its heavy winds would push the vast, exposed bulk of the Lion northeast toward the Aleutians at an increasing speed, until there was nothing anyone could do but pray she sank before she made landfall. If she stayed afloat, McKenna knew, she’d be on the beach within a couple of days.

McKenna called the crew to the wheelhouse. They crowded in, Matt and Stacey and Court Harrington around the chart table, Nelson Ridley beside McKenna at the wheel, Al and Jason Parent by the doorway, and Spike on the dash. They looked out at the Pacific Lion , the Salvation at her stern, her flimsy towline drawing taut, then slackening as the waves battered both vessels, the Salvation ’s black exhaust nearly obscuring the Lion ’s stern.

“He’s got to get her moving,” Ridley muttered. “What in hell is Magnusson doing, farting around over there?”

Читать дальше

![Маргарет Оуэн - Спасти Феникса [litres]](/books/405290/margaret-ouen-spasti-feniksa-litres-thumb.webp)

![Оуэн Дэмпси - Белая роза, Черный лес [litres]](/books/412437/ouen-dempsi-belaya-roza-chernyj-les-litres-thumb.webp)