It was impossible that the ship would survive. Sooner or later, the water would rush in, dragging the ship down and Ishimaru with it, drowning him in the darkness. He reached for the door, fumbled with it and pulled it open, hoping that it led to the outside world.

It didn’t. It led to more darkness, a gaping, yawning maw. Blinded and crippled, he gripped the briefcase and crawled across the threshold, realizing too late that he’d found a staircase skewed crazily by the list of the ship, the walls and the floors not where they should have been.

He fell. Tumbled through darkness, too surprised even to call out, his body battered against unforgiving steel walls and railings, against the stairs themselves. He came to land again, a heap of broken bones and sprains, lay there for a while, vomiting and passing out and waking to vomit again.

He gradually came to realize he’d landed near another door. A hatch. It could lead to daylight. It could lead to a flooded compartment and certain death. It could lead to nothing at all, to more darkness. But there was nothing else that Ishimaru could do.

He struggled to open the hatch. Propped himself up and wrenched at the lever and, finally, pushed the hatch open. It swung down into nothingness. Ishimaru took the briefcase and crawled through, more carefully this time. Searched with his hands for a suitable landing spot.

There was a wall to his left. It met the listing deck so as to form a triangle. Ishimaru crawled into its cradle, intending to follow the wall to wherever it led. He was thirsty and hungry and in constant pain. He must have spent a day on the wreck by now, maybe more, and he realized with a surprising aloofness that he would probably die in the darkness. But he took the briefcase anyway, dragged it behind him through the hatchway until it came to its end, a few feet beyond.

There was nothing after it. There was a hole. It might have been six feet deep, or sixty feet; there was no way to tell. Ishimaru was exhausted, and his whole body was sore. He’d lain against the wall and the deck of the ship and listened to the monstrous, primeval noises around him. He closed his eyes and waited to die. Waited to be released from the memory of what he’d done.

Naoko. Saburo. Akio.

He’d killed them all.

• • •

EXCEPT NOW, HERE WAS LIGHT , and a man’s voice calling his name. “The briefcase, Tomio,” the man was saying in Japanese. “Where is your briefcase?”

Ishimaru struggled to straighten himself. Failed to move his head more than a few inches. He blinked in the sudden brightness, surveying the platform in the light of the man’s headlamp. It was narrow, an ugly yellow, hard steel. Beyond it were the ghostly forms of cars hanging in rows to oblivion. And where was the briefcase?

The briefcase was not on the platform. Ishimaru remembered dragging it through the hatchway, remembered setting it down as he lay his head against the wall. He remembered now the sudden shudder of a large wave, jolting him awake from his delirious state. He remembered feeling the briefcase at his feet, kicking at it reflexively, then not feeling the briefcase anymore. He realized what he must have done.

“The briefcase, Tomio. Where is it?”

The man’s light was blinding. Still, Ishimaru recognized the voice. “Hiroki?”

“Yes,” Okura said. “It’s me, Tomio. All is safe now. But where is your briefcase?”

Ishimaru rolled his eyes to look over the edge of the platform. Okura followed his gaze with the light. There was no sign of the briefcase amid the cars and the darkness, but Ishimaru knew it must be down there somewhere. Okura grabbed him, rough. Shook him. “Talk to me, Tomio.” His voice desperate, urgent, unhinged.

Ishimaru lifted his chin and gestured over the edge. “Down.”

Okura peered over the edge of the platform. He swore. He looked at Ishimaru and swore again.

Okura stared down at Ishimaru. The stowaway was filthy and bruised and broken, a pitiful creature. The sight of him filled Okura with hot, sudden anger.

All you had to do was hold on to the briefcase, he thought. You could have made us rich. Well, me, anyway.

Ishimaru clawed at him, weak as a baby bird. “Water,” he rasped out. “Please.”

Okura ignored him. Shined his headlamp into the gloom again. Searched for any sign of the case, couldn’t see it. He kicked Ishimaru’s hand aside. Inched across the bulkhead to stand over him on the platform. Stared down at him for a long time—the stowaway feeble, blinking, near blinded by the light—and felt his anger only worsen.

Before Okura realized what he was doing, he’d put his foot down on his old classmate’s throat, stepped down hard.

It would be impossible to bring Ishimaru to the surface. The stowaway’s presence would bring more complications. It would raise questions that would stand in the way of Okura’s freedom.

This is the only way.

Ishimaru was too weak to fight. He clawed ineffectually at Okura’s boot. Gasping, his eyes bulging. Okura maintained the pressure, watched the desperation in Ishimaru’s eyes turn to surrender. And then those eyes went vacant and his old classmate was finally dead.

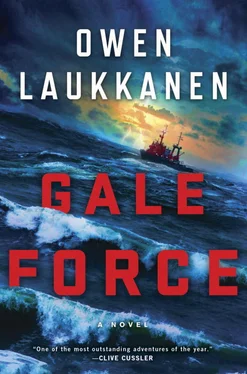

McKenna watched through her binoculars as the man emerged from the bridge of the Lion , climbed into a skiff tied to the freighter’s railing, and navigated it, slowly and perilously, back to the Salvation . Beside her, Court Harrington shifted his weight.

“What’s that about?” he asked. “Who’s that guy?”

McKenna shrugged. “One of Christer’s guys, I guess. Could be his architect. You recognize him?”

She handed Harrington the glasses, and the whiz kid studied the man in the skiff. “Nobody I know,” he said. “Whoever he is, he’s got guts to be running that dinghy through those waves.”

“Or he’s just crazy.” McKenna took the glasses back. The man had reached the Salvation , which rode the waves at the stern of the Lion , tethered to the bigger ship like a terrier on a leash, black plumes of smoke belching out of her stack.

Cripes, even the towline seemed thin for the job. The winch looked underpowered, too, and the Salvation herself was dirty, in need of a fresh coat of paint. She was doubtless a good ship—hell, she’d survived since World War II—but she wasn’t a salvage tug, and with the weather set to turn, McKenna wasn’t about to stand around waiting for Christer Magnusson to prove it.

She picked up the radio. “Coast Guard cutter Munro , this is the Gale Force .”

A pause. Then: “ Gale Force , Munro . We were just about to hail you, sir—er, ma’am. Can you tell me your intentions in these waters?”

“Sure,” McKenna said. “I’m here to salvage the Lion .”

A longer pause. “Ma’am, it’s our understanding that Commodore Towing is handling salvage duties at this time. Have you been in touch with the Salvation ?”

“I have,” McKenna said. “I told them they’re wasting your time. That little boat over there is pouring its heart out and it can’t move the Lion . What’s going to happen when this gale hits?”

“As far as we’re aware, Commodore’s operations are proceeding as planned,” the radio operator replied. “If you wish to assist, I’d suggest you try to negotiate something with the Salvation herself. We’re not in a position to be settling disputes of this nature.”

“You will be,” McKenna said. “When the operation fails and the Lion wrecks on a rock somewhere, you’ll have a mess on your hands, I assure you.”

Читать дальше

![Маргарет Оуэн - Спасти Феникса [litres]](/books/405290/margaret-ouen-spasti-feniksa-litres-thumb.webp)

![Оуэн Дэмпси - Белая роза, Черный лес [litres]](/books/412437/ouen-dempsi-belaya-roza-chernyj-les-litres-thumb.webp)