“Don’t worry, shit head; I’ve no intention of hurting you,” Lev snarled, contradicting himself with a boot to my ribs, “and I’m certainly not going to kill you.”

“Well, that’s good news,” I said, once I’d caught my breath and wondered if he’d cracked a rib.

“I’m going to let Dubai do that for me,” Lev said, hauling the chair and me into a vertical position again. “But until then I need you to go to sleep again.”

The blow he gave me gave him what he wanted.

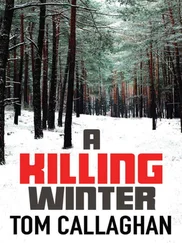

When I came round for a second time, I was bitterly cold and no longer indoors. My hands were still tied together and I was sprawled across the back seat of a car lurching and bouncing along a very uneven road.

“Welcome back,” Lev said. I could see his outline in the driver’s seat against the windscreen, with another figure, presumably Jamila, next to him. It was ink-black outside, and from the way the headlights leaped up and down in the darkness, I realized we were no longer in the city, but in the desert.

The expats call desert driving dune bashing, but the only things getting bashed were my kidneys. Apart from the occasional involuntary grunt as we bounced a little higher than usual, and the growl of the engine, the silence was absolute.

We drove like that for maybe an hour, with no one talking. Every now and then I heard the click of a lighter, watched the sudden flare pick out cheekbones and profiles, saw the orange spark of a cigarette. No one thought to offer one to the condemned man.

Finally I decided I’d had enough of meaningful silence.

“Where are we going, Lev? If you don’t mind me asking.”

He laughed, trying for one of those deep sinister chuckles that you hear in the movies, but only producing something that sounded like a dog sneezing.

“We’re going to play in the sand. Hide and seek. It’s a great game; you’ll love it.”

Then he laughed again, and this time he did sound like one of the bad guys. I decided to pass the time by using my tongue to check my teeth. A loose molar, but that was all the damage I could make out. The savage headache and the dizziness were much more worrying. So was the pain in my hip; I was lying on something hard. My Makarov. I wondered whether Lev had been so stupid as to not search me, or whether Lin had put it back in my pocket as a bizarre act of repentance. Somehow I favored the former option. Stupidity rules the world, after all.

We stopped, the nose of the car pointing down, so I realized we were on the crest of a sand dune. Lev opened the back door and hauled me out without ceremony. I felt the Makarov slip out of my pocket and into the sand. I felt as if my last chance had slipped away with it.

“I’m going to untie your hands,” Lev said. “You won’t be able to dig your own grave otherwise. But any smart tricks and I’ll shoot your kneecaps into splinters. You understand?”

“Clear as crystal,” I said and held my hands out in front of me. Lev decided to administer another bout of kicking and punching, just to make sure I was suitably subdued. Finally, out of breath, he untied my wrists, clearly hoping I’d try something, and was disappointed when I spent the next five minutes trying to rub some feeling back into my hands. I wondered if I’d live long enough to see the bruises I was surely going to have in the morning.

Lev threw down a spade next to me. I picked it up, debated rushing him, decided that I might as well get some exercise in before dying. So I started to dig. It’s not difficult to use a spade on sand. Where it gets tricky is stopping it trickling back into the grave you’re trying to dig. After an hour of working up a sweat to counteract the night chill, I was still only waist-deep in my future home.

Lev must have been just as bored as I was, so he called a halt, satisfied that the hole was deep enough. It was then that I started to sway, overcome with exhaustion, the rush of fear, the stink of approaching death. My eyes rolled in my head, I cried out in pain, the howl of a wolf in winter mountains, collapsed.

From a vast distance I heard Lev swear; he must have been looking forward to executing me. Sand cascaded over me as Lev readied himself to jump down beside me. As he did so, I raised the spade, edge on, toward where his face would be.

Lev saw what I was doing, but he’d already made his move and gravity did the rest for me. As he toppled forward, I braced the spade so that it bit into his face like an ax. Flesh split apart as if I’d smashed a watermelon, and I shut my eyes as warm skin and hot blood spat over me. The spade jarred in my hand as it cracked open his skull. There was a horrible splintering sound, a single choking grunt, and Lev’s body slumped beside me.

The temptation to lie still and vomit was irresistible, but I knew I had to act. I spewed out a combination of my last meal and bile as I used Lev’s body as a step to get out of the grave. Staggering toward the car, I stumbled, fell, scrabbled for the Makarov, found it and turned onto my back.

It was then that a bullet punched a hole into the car door a couple of centimeters above my head. It was instinct rather than judgment that made me return the shot, and I heard Jamila scream in pain. I didn’t know where I’d hit her, but I knew I had to stop her before she took better aim. We were too close together for her to miss a second time.

I could see her shape, like a black cloud, dark against the stars that filled the sky. I couldn’t help thinking how beautiful the night looked, eternal, far from human stupidity and greed and desire. Then reality kicked in, and I pulled the trigger three times. Each shot went home, and I heard the wet slap of blood hitting the side of the car. Then nothing.

I lay there for several years, debating whether to ever move again or whether to let the sun rise and kill me. Then I pulled myself up, wincing at the pain from my recent beating, and reached into the car to turn on the headlights to inspect my handiwork.

Jamila’s face was still intact, eyes open, mouth an O of shock. I’d hit her center mass, and the blood stained the front of her blouse a crimson black. One shot had taken away a kneecap, and her leg was bent at an unnatural angle, like a tree branch snapped in half during a storm.

I knew I hadn’t had a choice, but that didn’t mean I was proud of having shot a woman. I looked at Jamila, thrown down into the sand like an abandoned toy, and wondered how I had reached here, what exactly I had become.

I pulled at Jamila’s corpse so that she could spend eternity next to Lev. The body fell forward so that Jamila’s arm lay across Lev’s chest. As an embrace, it perhaps lacked a little passion, but I wasn’t going to rearrange the lovers. I slid down into the grave to retrieve the spade, scrambled on the bodies to get out, started to shovel sand over the corpses. It took several shovelfuls before I could cover Jamila’s staring eyes and the catastrophe of what had been Lev’s face.

Eventually the scouring wind would either bury them deeper or leave them exposed for someone to find, the flesh desiccated and taut across cheekbones, eye sockets deep and empty. But by then I’d be long gone, back by lakes and forests, mountains and snow. Or so I hoped.

Finally, I finished, threw the spade into the back seat, conscious that it carried my fingerprints, checked for water. I found a couple of bottles, emptied the first one down my throat, the second one over my hair and face. I went round to stand in the headlights and inspected myself as best I could. Not too bad; the good thing about sand is that you can brush most of it off.

I hauled myself into the driver’s seat, feeling worse than I could remember ever feeling, trying to block out the memory of Jamila’s accusing stare. I knew that time would weaken the image, but right there and then time was something I didn’t have.

Читать дальше