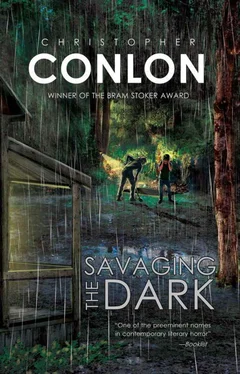

Christopher Conlon - Savaging the Dark

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Christopher Conlon - Savaging the Dark» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2014, ISBN: 2014, Издательство: Evil Jester Press, Жанр: Триллер, Ужасы и Мистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Savaging the Dark

- Автор:

- Издательство:Evil Jester Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2014

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-615-93677-2

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Savaging the Dark: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Savaging the Dark»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Her lover’s name is Connor. He’s got blonde hair, green eyes… and he’s eleven years old.

Savaging the Dark — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Savaging the Dark», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Mommy, what’s the matter?”

Something has gone wrong somewhere, something’s frayed and snapped, something’s broken but I don’t know what. I’m as absent-minded with Bill as I am with Gracie. I don’t remember to buy dinner, or if I buy it I lose myself watching TV and forget to cook it. Bill tries to be good-natured, sensing something amiss, trying to jostle me out of it: “C’mon, Mona, where are you? I know you’re in there somewhere.” But I’m not sure that I am. I’m not sure what I know and what I don’t know anymore. I know that I have trouble focusing at school, forget to grade assignments, leave the educational video at home that had been my lesson plan, neglect to make up the regular Friday quiz. My faculty room box overflows with unread catalogs, unopened circulars. But I never forget the books I promise Connor, or the old movies. I never forget that we have a lunch meeting each day.

None of this is really too bad—not yet. The efficient and high-functioning Mona Straw has become somewhat scatterbrained, that’s all. Her behavior is well within the range of normality for any person. People forget things. It’s true that she rarely forgot anything before, but she’s under a lot of stress. Having a husband and four-year-old daughter while holding down a full-time teaching job isn’t easy. Everyone understands that, everyone backs off, gives Ms. Straw, Mona, some slack. But Estelle rarely talks to me anymore, rarely makes eye contact.

The truth is that there are times I can hardly take my eyes off Connor Blue. I realize this about myself and try to make sure no one notices. There’s no one to see other than a bunch of middle-schoolers anyway, but they would if I weren’t careful. What would they think if they realized? They’re too young to imagine anything like, “Ms. Straw is in love with Connor!” The other way around, yes, but not that way, not at their age. And most certainly I am not in love with Connor. But at the same time I have trouble not staring at him, at his clear green eyes, his freckles, his small but muscular arm and graceful fingers as he moves a yellow pencil across a sheet of white lined paper. Yet he’s no different from any boy in my classes, any boy anywhere. I know that. Every period my room is filled with young boys with clear eyes and muscular arms and high young voices. Connor’s no different from the rest, I tell myself. Growing up with no mother and a cold, unsympathetic father? Let him join half the human race. Connor’s no different. He is not.

But I can’t convince myself of it, not during those private lunchtime sessions when he sits munching his daily apple and I watch him while trying to make sure it’s not obvious I’m watching him. I watch his Adam’s apple rise and then drop again as he swallows. I watch his eyes move across the pages of the movie book on the desk in front of him. I watch his left leg vibrating up and down and the slight movement of his foot within his sneaker.

“I want to see The Thirty-Nine Steps,” he says, looking up at me brightly.

“That’s a really old one,” I say, careful to hold my voice steady. “Hitchcock made that in the 1930s.”

“I know. I’d like to see all those early ones. The only one I’ve seen is The Lady Vanishes. They run that on TV.”

“Did you like it?”

“It was funny. Sometimes I can barely get what they’re saying, though. Like, the accent.”

“The English accent?”

“Yeah.”

“Are you saying that the English don’t speak good English?”

“Yeah! The English don’t speak good English!”

We both laugh. The sound he makes is very high, girlish. His face is luminous. Hardly aware of what I’m doing, I stand and move to his desk, sit down at the one next to him.

“See?” he says, pointing at a photo of Robert Donat and Madeleine Carroll. They are out on some studio-created moor, handcuffed together. “ The Thirty-Nine Steps. Looks good.”

“It is good,” I say, leaning toward the book, toward him. “I saw it years ago.” I rest my hand on the corner of his desk, studying the photo. I’m aware that our fingers—mine are much bigger and longer than his—are inches apart. I wonder if he’s aware of it too. I look at the handcuffed couple in the photo, and a picture flashes in my mind of handcuffs around Connor’s thin wrist with an unbreakable silver chain leading to another cuff around my own. The movie, I remember, raised all sorts of implicit questions about how a man and a woman who hardly know each other would behave when handcuffed together. How would they manage the toilet, or their sleeping arrangements? What possible modesty could they maintain? Such questions obviously delighted Hitchcock. I find my heart racing as I study the photo, our hands, Connor’s face in profile.

On his forearm, I notice, is an oval bruise, not too big, but impossible not to see. “What happened here?” I ask, pointing at it, my finger moving very close to his skin.

“That?” He looks at it as if he’s never seen it before. “I don’t know. I think I bumped into a door.”

His mustached, bartending father crosses my mind. I let it go.

“Have you seen The Lady Vanishes ?” he asks, turning the page and breaking the odd spell. I slip my hand off his desk and onto my lap.

“Yes, I have. You’re right, it’s very funny.” Ladies, vanishing—vanishing into what? In the movie, into thin air. Here, in this classroom? Into… the words child abuse erupt suddenly in my mind. A sense of panic stings me and I stand, knocking my chair back awkwardly. Connor looks up at me, his expression slightly puzzled. Looking down at his sweet sinless face, I mutter, “I—” but can’t manage to continue what I was going to say, if I was going to say anything at all. Sweat suddenly pours from me. My fingers and feet tingle. I back away from Connor, from the vision of the handcuffs and the bed and the bathroom, back away slowly as if he were some wild animal primed to attack and I his hapless victim.

“Ms. Straw? Are you okay?”

We’re in the same room together but we’re not, not really. We’re not in the same world. I walk carefully back to my desk, drop down in my chair, try to breathe. How ridiculous I must look to him, I think. How strange.

I swallow and will myself to speak my words evenly. “I’m fine, Connor. I’m glad you’re enjoying the book.” Then, unable to stop myself: “I’d love to watch one of those movies with you someday.”

I hurl myself into my work, spending extra hours on lesson plans and highly detailed grading and reading up in the kinds of educational journals that are always around in the faculty room but which I never bother to look at. I clean out my faculty box, glancing cursorily at the endless educational catalogs and offers and invitations from groups with names like Kidsplay and Mid-Level Readers’ Club and Youth Leadership for America before tossing them in the garbage. I focus on Lauren Holloway and Richard Broad and Kylie McCloud, I counsel them after school, I call home concernedly, I care as only the best teachers do. I focus on Gracie too, playing jacks and hopscotch with her, helping her make clothes for her dolls, watching cartoons with her, reading with her, fun-splashing her in the bathtub to make her laugh and squeal. She’s a wonderful child, actually. Very smart, very neat, pretty, mild-tempered. A mother could hardly ask for more. And I focus on Bill, I ask him how his work day has gone, make him his favorite dinners, rent movies I know he’ll like—recent special-effects blockbusters, he’s bored by old classics—and initiate activities in bed we’ve not done in years, or sometimes ever. He’s flattered by all the attention but clearly a bit mystified by it as well. “Is everything all right, Mona?” Of course, everything is fine, how could it not be, what could possibly be wrong?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Savaging the Dark»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Savaging the Dark» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Savaging the Dark» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.