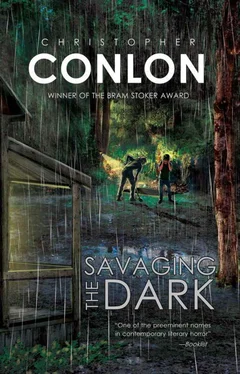

Christopher Conlon - Savaging the Dark

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Christopher Conlon - Savaging the Dark» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2014, ISBN: 2014, Издательство: Evil Jester Press, Жанр: Триллер, Ужасы и Мистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Savaging the Dark

- Автор:

- Издательство:Evil Jester Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2014

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-615-93677-2

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Savaging the Dark: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Savaging the Dark»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Her lover’s name is Connor. He’s got blonde hair, green eyes… and he’s eleven years old.

Savaging the Dark — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Savaging the Dark», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I know he needs time with kids his age. I know he needs a chance to be a boy. Yet I feel a terrible sadness watching him. He never once asked me that day if we could spend time together, didn’t plead to be allowed to watch a movie in my classroom, didn’t try to whisper something to me after class after the other children had gone.

Something darkens and sinks inside me. The day is bright but the light seems somehow wrong to me, glaring, accusing. Like the light on some alien planet, not meant for humans to see. Poisonous, deadly. I wonder if Connor is thinking of me at all as he runs up and down the field, if I cross his mind, if there’s some part of him that wishes he could be with me right now or if he’s forgotten all about what we are to each other. When I take him aside the next day and tell him what corner to meet me on that afternoon, he says casually—not negatively but casually, as if it’s of no importance—“Oh, okay.” When I pull up to him on the sidewalk and he sees me his face doesn’t light up, it doesn’t become suffused with that apple-glow in the way it did in our dozen or more earlier sessions. He smiles, that’s all, gets in. Doesn’t say a word. Doesn’t ask what motel we’re going to, how close it is, doesn’t ask little-boy questions about anything we’re passing by on the way there. I feel something’s changed between us but I’m afraid to ask what, afraid to even breathe a suggestion to him that his behavior around me seems different. When we get to the room (the “Kings Court Motel”), he jumps on one of the beds, grabs the TV remote and switches on the set, all but ignoring me.

“Baby,” I say, dropping down beside him, taking the remote from his hand and switching it off, “we don’t have much time.”

“Oh, okay.”

Not unpleasant. Not frowning or complaining. And once we’re making love it’s just as it’s always been, wonderful, indescribable, yet even now something’s subtly altered. I straddle him and stroke his chest and dangle my hair playfully in his face and move rhythmically with him inside me and he doesn’t respond . He’s there, he thrusts himself into me, his hands are warm on my hips, he smiles when I say anything to him, but his eyes are somehow vacant. And now when we finish once he doesn’t ask to do it again, instead allowing me to hold him for a few minutes and then saying he has a lot of homework to do and we should get back.

“Connor, sweetheart, we have time, just a few more minutes.”

But it could be my imagination. He’s still pleasant, smiling, fun. We still talk, we still make jokes, act silly.

“Mona?” he asks once in bed. “Do you think that Rick and Ilsa had sex in Casablanca?”

“I’m sure they did, baby.”

“What about John and Frances in To Catch a Thief ?”

“Cary Grant and Grace Kelly? They’d better have! I’d have sex with either one of them.”

Connor laughs, the old laugh, the high boy-giggle I know. “You’d have sex with a lady?”

“I’ll bet you’d have sex with her if she let you.”

“Well, yeah,” he says, running his finger from my nipples to my navel, “but I’d think about you when I was doing it.”

We laugh, we roll around the bed, everything is as before. But such moments seem to happen with decreasing frequency. Connor grows ever more quiet, even now, at times, moody. I try not to become hysterical about this, try to keep from thinking that he’s losing interest, that I’m losing him. There’s no evidence of it, after all. He’s a boy. He’s supposed to be moody sometimes. It just means he’s grown more comfortable with me, that’s all, he feels he can express more of his real self around me, be more natural and easy with me. At times after we finish I hold him, run my hand over his hair as I did that first time, the first time I knew there was something unexplored and magical between us, and ask him how he’s doing, how his life is—“Are you happy, Connor? With me? With everything?” And we have beautiful heart-to-heart talks, just the two of us, about his fears, his joys, his sadnesses.

One rain-filled afternoon he tells me how much he misses his mother. “Even though I never knew her. Isn’t that weird, to miss somebody you never knew?”

“It’s not weird, sweetheart.” I stroke his hair. “She died when you were…?”

“Two.”

“Two.”

“I don’t remember her. I’ve tried. It’s like sometimes I think I can almost hear her voice or, like, see her or something like that. But it always goes away.”

“I’m sorry, sweetie. I wish I could make it better.”

We sit listening to the rain outside the dirty motel room and I wait for him to say something like You always make everything better, Mona, but he doesn’t. He remains wordless, motionless, accepting my touch but not reciprocating. After a while when it’s nearly time to leave he gets up and goes to the bathroom, turns on the shower without me, doesn’t invite me in. I shower alone after he’s done and we drive back to the city in silence.

Another time there’s a bruise on his left bicep, a purple and yellow stain.

“Connor,” I say carefully, touching it softly around the edges with my finger, “does your dad hit you?”

He looks away.

“You can tell me, Connor.”

After a long time he says, “I guess. I mean, sort of.”

“Sort of?”

He shrugs. “He pushes me sometimes. When he’s drunk.”

“Oh, Connor.” I nuzzle him. It crosses my mind that I would call child protective services, but then it crosses my mind that of course I can’t do any such thing. I hate Connor’s father even more now. “Connor, I’m so sorry.”

I become aware of a new element only gradually, and at first I’m unable to believe it. It begins at the afternoon dance we have in March, to celebrate the coming of spring. The eleven- and twelve-year-olds are herded into the school’s gym one afternoon. We on the staff have decorated it with streamers and balloons and Dave Tisdale, the science teacher, serves as DJ. There’s punch and cookies in the back of the hall. The lights are turned low—slightly low, at least. It’s a socialization exercise, we do it twice a year at Cutts. It’s always cute to watch the young boys nervously approach the girls, the girls hiding in packs so as not to be invited out to the dance floor—for a while, anyway. After a few songs their courage grows stronger and they largely separate, make themselves available, and soon the floor is covered with clumsy middle-schoolers dancing to rock music.

Connor stays in the back, playing checkers with the other boys too shy to become part of the social swim. I watch him, wish I could walk over to him, take his hand, walk out to the dance floor and embrace him in a slow dance no matter what music is playing. I wish I could stroke him, kiss him, announce to everyone there what we are, how we have something between us that they can never understand, that we love each other. But no. Instead I sit there with several other teachers blandly chaperoning, never actually doing anything except once when I stand and wander the perimeter for a few minutes, saying hi to kids, letting them know I’m here.

But when I turn to go back to my spot I’m confronted with an astonishing sight.

Connor, Connor Blue, my love, my lover, is walking nervously out onto the dance floor just in front of my quiet little book-reading student Kylie McCloud.

A fast song has started and they gyrate as best they can. I’m surprised to see Connor dancing but I’m flabbergasted to see Kylie, backward shy Kylie, out there. Neither of them can dance at all but of course that makes no difference, it’s not the point. Kylie’s short mousy hair bounces, her glasses slip down her nose as they always do, she watches her dance partner with her head slightly uptilted and her mouth open a little. I wonder if she needs her asthma inhaler. At this moment I couldn’t be prouder of Connor, taking the little girl no one likes and making her a part of things.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Savaging the Dark»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Savaging the Dark» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Savaging the Dark» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.