Peter hugged her back, and they held their embrace for nearly a minute. Then, with a final kiss, a goodbye, and a promise to be safe, the two parted ways. One left for the safety of a hardened nuclear bunker. The other for his condo, his mind full of conflict as to what he should do.

PART VII

ONE WEEK IN OCTOBER

Day seven, Thursday, October 24

Thursday, October 24

Mount Weather Emergency Operations Center

Northern Virginia

The 2008 Democratic primary campaign advertisement had been deemed one of the best in modern history. The scene, ominous, if not creepy, began in the middle of the night. It was 3:00 a.m. Sleeping children. A ringing telephone. The undertone of a matter of grave importance in the narrator’s voice. It was a who-do-you-want-in-charge, Cold War-esque display asking voters whom they trusted to lead the country during a world crisis when that phone rang in the middle of the night.

Every president had their three-in-the-morning phone call moment. This was President Carter Helton’s. Ironically, just after 3:00 a.m.

He was awakened by his chief of staff, and he hurriedly dressed in a pair of Penn State University sweats. There was no time for decorum, as nuclear weapons had been launched once again.

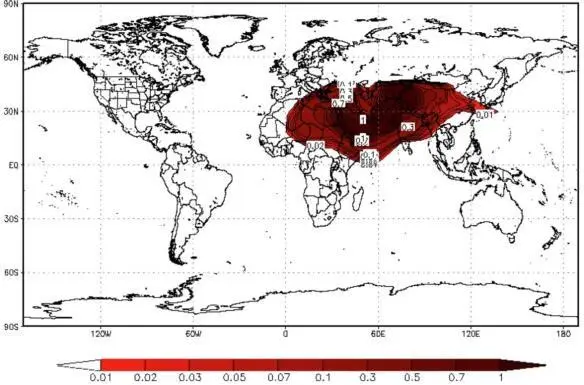

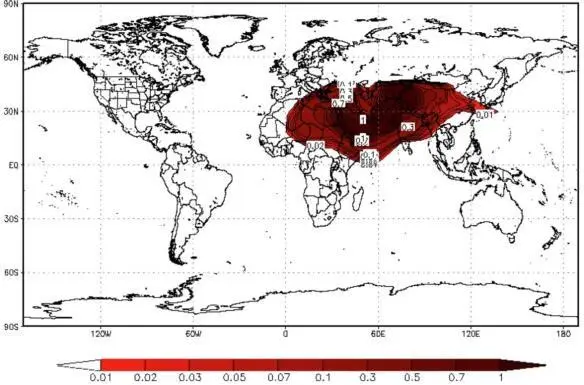

North Korea had been relatively quiet throughout the exchange of ballistic missiles in South Asia. In the past twenty-four hours, that had changed. During the DPRK’s 13th Party Congress, Kim did a lot of chest-puffing. Apparently, he was prepared to follow through on his threats.

Most analysts believed if a second Korean war broke out with the use of nuclear weapons, it would be deadly, producing millions of deaths just in the South Korean capital of Seoul. However, if North Korea deployed their nuclear arsenal toward Japan as well, countless more millions would die.

Following the war handbook developed by Russia, the North Koreans had amassed troops and accompanying military assets on the border with South Korea in a show of force. Many thought they were feigning an invasion in an attempt to gain concessions at the UN bargaining table.

Then, mere minutes ago, they fired two nuclear-tipped ICBMs into South Korea. The first was successfully destroyed by the U.S. Aegis ballistic missile defense system located in Japan. The second warhead struck the heart of Seoul, vaporizing a million South Koreans instantly.

Seconds after the Aegis missiles were fired from Japanese soil, Kim turned his sights on Tokyo. He immediately declared war on Japan and initiated the launch sequence. Within minutes, three ICBMs were launched from missile silos on the east coast of North Korea toward Japan.

Tokyo’s population of nine million plus lived in one of the highest density cities in the world. Two of the three ICBMs found their marks, devastating the city, including the famed Imperial Palace. Once again, the Aegis defense system worked, but with only marginal success.

Kim wasn’t through yet. He saw the use of the U.S. built and maintained Aegis system being deployed against his nuclear arsenal as being tantamount to Washington declaring war on Pyongyang. He chose to ignore the defensive nature of the Aegis deployment.

He fired four ICBMs across the Pacific toward the West Coast of the United States and one toward Hawaii in rapid succession. Their estimated time of arrival was half past the hour of three in the morning. They were followed by a second wave of three more ICBMs that followed a different path over the Arctic Circle toward East Coast targets.

The U.S. missile defense system was a global network with twenty-four-hour surveillance by land, sea, and space-based sensors, all of which were constantly looking for signs of anything amiss in North Korea. Regional missile interceptors were deployed in Japan, South Korea, Guam and on U.S. Navy ships, while military bases in Alaska and California were equipped to intercept missiles headed toward the United States.

When North Korea launched their missiles, U.S. satellites detected them almost instantaneously through infrared signals. In less than a minute, the satellites raised the alarm, and the command-and-control center at Schriever Air Force Base near Colorado Springs, Colorado, sprang into action.

Minutes later, President Helton entered the operations center at Mount Weather. Thus far all decisions made in the defense of South Korea and Japan had been made by pre-established protocols and programmed responses. The same was true of the U.S. intercepts of the incoming ICBMs.

The command center at Cheyenne Mountain in Colorado immediately got involved. They directed the radars in the region to track the multiple missiles as they climbed toward outer space. During that five-to-seven-minute period of time, the radar systems gathered data, like trajectory, velocity and altitude, to send back to the command center. Complex computer analysis was applied so the military could identify what type of missile was launched and whether it could reach the U.S.

During this boost phase was the ideal time to intercept a missile, but the current defense system wasn’t equipped to do so yet.

Normally, the officers at the command center would consult with U.S. Northern Command, Northcom, based at Peterson Air Force Base in Colorado Springs, where a round-the-clock watch officer would be responsible for approving an interceptor launch. If there was time, they might notify the secretary of defense in Washington, too.

However, under the circumstances, all hands were on deck, and the president himself was included in the discussions. It was agreed. Launch orders were approved and sent to Fort Greely and Vandenberg Air Force Base, both of which were best positioned to intercept.

It had been ten minutes since the North Korean missile launches were first detected. America’s ground-based interceptors, or GBIs, were the only weapons capable of destroying an ICBM. Until that early morning on the seventh day of the global nuclear war, they’d only been tested against such a missile once—with success.

The U.S. only had thirty-six GBIs—four in California and thirty-two in Alaska. The secretary of defense recommended they launch two-to-three GBIs per incoming missile to improve the odds of success during an attack. That stockpile reduced the American defenses, and those advising the president cautioned U.S. defenses could theoretically be overpowered if North Korea were to fire multiple missiles after these first two barrages.

The president immediately ordered a counterstrike. While they acted to defend American soil, he surmised, they should shut down Kim’s ability to hit them twice. The launch sequence was initiated, and seven powerful ICBMs were launched from their missile silos in the Northern Rockies toward North Korea.

At this point, the North Korean warheads were three-quarters of the way through their thirty-minute journey to the U.S. The military’s success in defending against the multiple ICBMs was equated with hitting a bullet with another bullet. It had been done in simulations.

Against a single incoming ICBM.

In their simulations, never had the nation’s nuclear defenses fought off multiple incoming missile threats at once.

“Ten minutes to first strike,” a computer-generated voice announced through the operation center speakers mounted overhead.

There was nothing else for them to do. The launches, both defensive and offensive, had been effectuated. Now a president, and those in control of America’s military might, waited.

While warning alarms and sirens were activated from sea to shining sea.

Читать дальше