VIKING

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Simultaneously published in hardcover in Great Britain by Bantam Press, an imprint of Transworld, a division of Penguin Random House Ltd., London, in 2021.

First American edition published by Viking in 2021.

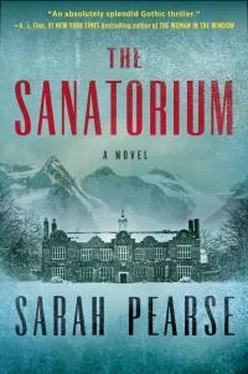

Copyright © 2021 by Sarah Pearse Ltd.

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

A Pamela Dorman Book/Viking

library of congress cataloging-in-publication data

Names: Pearse, Sarah, author.

Title: The sanatorium: a novel / Sarah Pearse.

Description: [New York]: Pamela Dorman Books; Viking, [2021]

Identifiers: LCCN 2020016188 (print) | LCCN 2020016189 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593296677 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593296684 (ebook)

Subjects: GSAFD: Mystery fiction.

Classification: LCC PR6116.E169 S26 2021 (print) | LCC PR6116.E169

(ebook) | DDC 823/.92—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020016188

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020016189

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Cover design: Ervin Serrano

Cover images: (building) David Clapp / Getty Images; (snowy mountains) Buena Vista Images / Getty Images; (frost) Shutterstock

pid_prh_5.6.1_c0_r0

For James, Rosie, and Molly,

It’s a long way to the top (if you wanna rock ’n’ roll . . . )

—ac/dc

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

Chapter 71

Chapter 72

Chapter 73

Chapter 74

Chapter 75

Chapter 76

Chapter 77

Chapter 78

Chapter 79

Chapter 80

Chapter 81

Chapter 82

Chapter 83

Chapter 84

Chapter 85

Chapter 86

Chapter 87

Chapter 88

Chapter 89

Chapter 90

Chapter 91

Chapter 92

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

On nous apprend à vivre quand la vie est passée.

They teach us to live when life has passed.

—Michel de Montaigne

I have loved constraints. They give me comfort.

—Joseph Dirand

prologue

January 2015

Discarded medical equipment litters the floor; surgical tools blistered with rust, broken bottles, jars, the scratched spine of an old invalid chair. A torn mattress sits slumped against the wall, bile-yellow stains pocking the surface.

Hand clamped tight around his briefcase, Daniel Lemaitre feels a sharp wave of revulsion: it’s as if time has taken over the building’s soul, left something rotten and diseased in its place.

He moves quickly down the corridor, footsteps echoing on the tiled floor.

Keep your eyes on the door . Don’t look back.

But the decaying objects pull at his gaze, each one telling stories. It doesn’t take much to imagine the people who’d stayed here, coughing up their lungs.

Sometimes he thinks he can even smell it, what this place used to be—the sharp, acrid scent of chemicals still lingering in the air from the old operating wards.

Daniel is halfway down the corridor when he stops.

A movement in the room opposite—a dark, distorted blur.

His stomach drops. Motionless, he stares, his gaze slowly picking over the shadowy contents of the room—a slew of papers scattered across the floor, the contorted tubes of a breathing apparatus, a broken bed frame, frayed restraints hanging loose.

He’s silent, his skin prickling with tension, but nothing happens.

The building is quiet, still.

He exhales heavily, starts walking again.

Don’t be stupid , he tells himself. You’re tired . Too many late nights, early mornings.

Reaching the front door, he pulls it open. The wind howls angrily, jerking it back on its hinges. As he steps forward, he’s blinded by an icy gust of snowflakes, but it’s a relief to be outside.

The sanatorium unnerves him. Though he knows what it will become—has sketched every door, window, and light switch of the new hotel—at the moment, he can’t help but react to its past, what it used to be.

The exterior isn’t much better , he thinks, glancing up. The stark, rectangular structure is mottled with snow. It’s decaying, neglected—the balconies and balustrades, the long veranda, crumbled and rotting. A few windows are still intact, but most are boarded up, ugly squares of chipboard scarring the façade like diseased, unseeing eyes.

Daniel thinks about the contrast with his own home in Vevey, overlooking the lake. The contemporary, blockish design is constructed mostly of glass to take in panoramic views of the water. It has a rooftop terrace, a small mooring.

He designed it all.

With the image comes Jo, his wife. She’ll have just gotten back from work, her mind still churning over advertising budgets, briefs, already corralling the kids into doing their homework.

Daniel imagines her in the kitchen, preparing dinner, auburn hair falling across her face as she efficiently chops and slices. It’ll be something easy—pasta, fish, stir-fry. Neither of them are good at the domestics.

The thought buoys him, but only momentarily. As he crosses the car park, Daniel feels the first flickers of trepidation about the drive home.

The sanatorium wasn’t easy to get to in the best of weather, its position isolated, high among the mountains. This was a deliberate choice, engineered to keep the tuberculosis patients away from the smog of the towns and cities, and keep the rest of the population away from them.

But the remote location meant the road leading to it was nightmarish, a series of hairpin bends cutting through a dense forest of firs. On the drive up this morning, the road itself was barely visible—snowflakes hurling themselves at the windscreen like icy, white darts, making it impossible to see more than a few yards ahead.

Daniel’s nearly at the car when his foot catches on something, the tattered remains of a placard, half covered by snow. The letters are crude, daubed in red.

Читать дальше