Bruce liked the story, but felt it was a little too graphic for his female readers, even though we all knew they didn’t exist. Could he use it without the last line?

Without the last line, of course, there’s no story. And the only reason I wrote the story a second time was so that I could reuse the last line. So I displayed artistic integrity I never knew I had and withdrew the story. I don’t know what difference I thought it would make, since nobody read anything in that magazine anyway, but for once I just couldn’t stop myself from doing the right thing. Gallery wound up taking it, last line and all. It was published as “Hot Eyes, Cold Eyes,” and was later included in my second collection, Like a Lamb to Slaughter.

3. The title deserves explanation. Most of these stories were written in a single sitting. I would get an idea and sit down at the typewriter and hammer it out. You can hold a short-story idea entirely in the mind, especially the sort of brief and uncomplicated story that most of these are. A weekday evening or a weekend afternoon was generally time enough to see one of these stories through to the end.

It still often is. I still write stories rapidly, and sometimes complete one in a single setting. The major difference, it seems to me, is that the gestation period has gotten a lot longer. I’ll nowadays let a story idea percolate or ferment or stew for days or weeks or months. Back then I tended to strike as soon as the iron was hot, or, occasionally, before it had really warmed up.

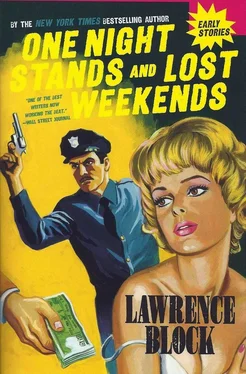

I’ve had three collections of short stories published, plus a small-press collection of the Ehrengraf stories and Hit Man , an episodic novel comprising the Keller stories. One Night Stands consists of stories deliberately omitted from these collections (or ones I’d lost track of, but if I’d had them handy I’d still have left them out).

What have we got here, then? A box labeled “pieces of string too small to save”? If they weren’t worth collecting, why have I collected them?

I’ve been guided by the same principle (or, some might argue, the same lack thereof) that has led me to republish some early crime novels that I’d be hard put to read without cringing. The fact that I can’t read them with pleasure doesn’t mean someone else couldn’t, or shouldn’t. I’ve decided it’s not my job to judge my early work. Let other people make what they will of it.

Then, too, I’m not unmindful of the interests of collectors and readers with a special interest in an author — in this instance, myself. I don’t collect books, but I have other collecting interests, and I understand the mind set. Of course a collector would want a writer’s early work, to read or simply to have and to hold, and why should I deprive him of the opportunity? And why shouldn’t some scholar with a thesis to write have access to that early work?

At the same time, I don’t think these stories are much good, or representative of my mature work. For God’s sake, when I wrote these my typewriter still had training wheels on it. So I’ve decided One Night Stands should have limited distribution, going not to general readers but to collectors and specialists. Thus it’s being published only in a limited collector edition, and not, as is generally the case with Crippen & Landru publications, in trade paperback as well.

Enough! This introduction has passed the 2500-word mark, which makes it longer than many of the stories it’s introducing. It’s taken most of the morning to write it, too. May you, Dear Reader, like the tomcat who had the affair with the skunk, enjoy these stories as much as you can stand.

Lawrence Block

Greenwich Village

1999

The shorter of the two boys had wiry black hair and a twisted smile. He also had a knife, and the tip of the blade was pressed against Dan’s faded gabardine jacket. “Why’d you have to get in the way?” he asked, softly. “Every bull from here to Memphis is after us, and Pops here has to...”

“Shut up.” The older boy was taller, with blond hair that tumbled over his forehead. He, too, had a knife.

“Why? He ain’t going to tell anybody...”

“Shut up, Benny.” He turned to Dan, smiling. “We need money, maybe some food. We better make it over to your shack.”

“No shack,” Dan said. He gestured toward an opening in the wall of rock that edged the valley. “I live in the cave over there.”

Benny started to laugh, and the blade of his knife pierced Dan’s skin and drew blood. “A cave!” he exploded. “Dig, Zeke — he’s a hermit!”

Zeke didn’t laugh. “C’mon,” he said. “To the cave.”

They walked slowly across the field toward the mouth of the cave. Dan felt the sweat forming on his forehead, felt the old familiar sensation that he hadn’t felt since Korea. He was afraid, as afraid as he’d ever been in his life.

“Faster,” Benny said, and again Dan felt the knife prick skin. It didn’t make sense. He’d lived through a world war and a police action, and now two kids from Memphis were going to kill him. Two kids who called him “Pops.”

The veins stood out on his temples, and he could feel the sweat running down his face to the stubble of beard on his chin. “Why did he get in the way?” the kid had asked. Hell, he didn’t mean to get in anyone’s way. Just wanted to go off by himself, fool around with a little prospecting, and relax for a while.

They were almost at the entrance of the cave. Now they would take his money, eat his food, and put a switchblade knife between his ribs. He was finished, unless he managed to get to his gun in time. There was a shiny black .45 waiting on his shelf, if only he could get to it before Benny got to him with the knife.

“Here it is,” he said. He stepped inside the cave, the two boys right behind him. It was a large cave, wide and roomy and branching out much wider in the rear. On one side was his mattress, on the other his trunk and four orange-crate shelves.

“Let’s go,” said Zeke. “Bring out the dough and some food. We ain’t got all night.”

“Yeah,” Benny echoed. “We gotta roll, man. Make it fast or I stick you, dig?” He prodded Dan with a knife for emphasis.

“Wait a minute.” Dan’s eyes darted desperately to the crates and lighted on the kerosene lantern. “Let me light the lamp over there. It’s getting kind of dark in here.”

Benny looked at Zeke, who shrugged. “Okay,” he said. “But don’t try anything.” Dan walked across to the side of the cave, and Benny followed with the knife.

Fumbling in his pocket for a match, Dan glanced down to the middle shelf of the crate where the gun nestled cozily amidst a packet of letters and a pair of socks. If only he could get it, and if only it were loaded. Was it loaded? He couldn’t remember.

“Hurry it up,” Zeke said. It was now or never, Dan thought. He lifted the pack of matches from his pocket, tensed his body, and fell forward.

At the same time he lashed out viciously with his foot and heard a dull grunt of pain as he connected solidly with Benny’s belly. His right hand snaked out for the gun and closed around it, his fingers caressing the smooth metal of the butt. All in one motion he took it and whirled around, his finger tight against the trigger. The boys scampered for the rear of the cave. Then, before he could get a shot off, his right ankle buckled and he fell to the floor. For a moment everything went black as the pain shot up and down his leg. He gritted his teeth until the floor stopped spinning.

Dan glanced around the cave, and the two boys seemed to have disappeared. He tried to stand, but the stab of pain in his ankle told him it was useless. The ankle was broken.

Читать дальше