One weekend afternoon, I sat down at the kitchen table on Barrow Street and wrote “You Can’t Lose.” It was pretty much the way it appears here, but it didn’t end. It just sort of trailed off. I showed it to a couple of friends. I probably showed it to a girlfriend, in the hope that it would get me laid, and it probably didn’t work. Then I forgot about it, and at the end of October I went back to campus.

Where at some point I remembered the story and dug it out and sent it to a magazine called Manhunt. All I knew about Manhunt was that most of the stories in Evan Hunter’s collection The Jungle Kids had first appeared in its pages. I’d admired those stories, and it struck me that a magazine that would publish them might like my story. So I sent it off, and it stayed there for a while, and then back it came.

With a note enclosed from the editor. He liked it, but pointed out that it didn’t have an ending, and that it rather needed one. If I could come up with a twist ending, a snappier ending, he’d like to see it again. So I found a newsstand that carried Manhunt , bought a copy, read it, and wrote a new ending, one which at least proved I’d read O. Henry’s “The Man at the Top.” (My narrator ends with the triumphant boast that his ill-gotten gains are due to increase dramatically, because he’s just invested the whole thing in some gold mine stock. Or something.)

I sent this off, and it came back with another note, saying the new ending was predictable and didn’t really work, but thanks for trying. And that was that.

Then several months later the school year was coming to a close, and I was due to head off to Cape Cod and find a co-op job on my own. One night near the end of term I couldn’t sleep, and I lay there thinking, and thought of the right way to finish the story. I went home to Buffalo to visit my folks, drove out to Cape Cod, and wrote a new ending for the story. The acceptance process was slow — Manhunt had what we’ve since learned to call a cash-flow problem — but, long story short, they bought it. Paid a hundred bucks for it.

My first sale.

I left the cape after a month or so and wound up back in New York, where I got a job as an editor at a literary agency, reading scripts and writing letters to wannabe writers, telling them how talented they were and how this particular story didn’t work, but by all means send us another story and another reading fee.

I lived in a residential hotel on West 103rd Street, where my $65-a-month rent was again a fourth of my salary. And, nights and weekends, I wrote stories, which the agency I worked for submitted to various magazines. Most of the stories were crime fiction. I hadn’t yet decided I was going to be a crime fiction writer — I don’t know that that’s a decision I ever made — but in the meantime I read extensively in the field. There was a shop on Eighth Avenue off Times Square where they sold back copies of Manhunt and other digest-sized magazines ( Trapped, Guilty, Off-Beat, Keyhole, Murder , and so on) at two for a quarter. I bought every one of these I could find, and I read them cover to cover. Some I liked and some I didn’t, but somewhere along the way I must have internalized the sense of what made a story, and I wrote some of my own.

They sold, most of them, sooner or later. Sometimes to Manhunt , but more often to its imitators. Trapped and Guilty paid a cent and a half per word, so they were the first choice after Manhunt passed. Then came Pontiac Publications, at a penny a word. (Their magazines had titles like Sure Fire and Twisted and Off-Beat , and every story title had an exclamation mark at the end. I longed to call a story “One Dull Night” so that they could call it “One Dull Night!”)

After I’d been a month or so at the literary agency, it was clear to me I was learning more than I’d ever learn in college, and that I’d be crazy to stop now. So I dropped out and stayed right where I was. In the spring, I decided I’d learned as much as I was going to at the job, and that a student draft deferment was, after all, better than a poke in the eye with a sharp bayonet. I went back to Antioch.

By the time I got there, I was writing books. “Sex novels” was what we called them, though they’d now get labeled “soft-core porn.” I wrote one to order the summer before I returned to Antioch, and the publisher wanted more. So that’s what I did instead of classwork. And I also went on writing crime stories. At the end of that academic year, in the summer of 1959, I dropped out again, and this time it took. I started writing a book a month for one sex novel publisher, and other books for other publishers, and from that point the crime short stories were few and far between.

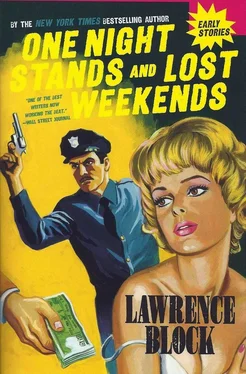

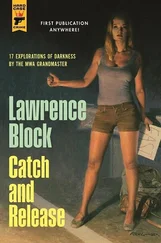

When Doug Greene and I discussed bringing out a collection of these early stories, he brought up the subject of an introduction. “You can read through the stories,” he said, “and write some sort of preface.”

“One or the other,” I said. “You decide which.”

I have a lot of trouble looking at my early work. I rarely like the way it’s written, and I especially dislike the glimpse it gives me of the unutterably callow youth who produced it. I like that kid and wish him well, but read what he wrote? The hell with that.

You know what? I’m afraid to read them. I’m scared I’ll decide not to publish them after all, and it’s too late for that.

So an uncharacteristic attack of honesty compels me to advise you that I am in the curious position of introducing you to a couple of dozen short stories that I myself haven’t read in forty years.

Someone else suggested that some of the stories might require revision, because attitudes expressed in them are out-of-date and politically incorrect. No way, I told him. First of all, one of the few interesting things about them is that they’re of their time. I’d much rather burn them than update them. And screw political rectitude, anyway. You want to go through Huckleberry Finn and change the name of Huck’s companion to African-American Jim? Be my fucking guest, but leave me out of it.

A few things you might want to know:

1. A few of these stories, as indicated in the bibliographical notes at the back, were published under pen names. This only happened when I wound up with more than one story in the same issue of a magazine. W. W. Scott, who edited Trapped and Guilty, would make up a pen name when this occurred, generally by working a variation on the author’s usual byline. Thus “B. L. Lawrence.” The guy at Pontiac asked what pen name to use in similar circumstances, and I provided the name “Sheldon Lord.” Were there other pen names? Maybe, because there have been editors in the business who had house names that they used at such times. Maybe they used them on stories of mine. I don’t think this ever happened, but at this point I’d have no way of knowing. And no reason whatever to care...

2. There’s a story in here called “Look Death in the Eye” that deserves comment. It may strike some readers as curiously familiar. I wrote it way back when, while I was working for the literary agent, and it sold to Pontiac, and I lost all track of it. Didn’t have a copy, didn’t know where to find one.

And I found myself thinking about the story. What I really liked about it was the last line, and that, really, was all I remembered. So I re-created the story from memory, right up to the last line, which I recalled word for imperishable word. I hammered it out and sent it off to a fellow named Bruce Fitzgerald, who was editing a magazine called For Women Only. (It was a beefcake magazine, as it happens, composed of outtake photos from Blueboy , a gay magazine. The stories and articles interspersed among the nude male pix in For Women Only were ostensibly slanted to female readers, of which I doubt the magazine had more than twenty nationwide. The idea was that, by being purportedly for women, it could get on newsstands closed to gay publications, where its true audience would, uh, sniff it out. Its name notwithstanding, it was really for men only. Publishing is a wonderful business.)

Читать дальше