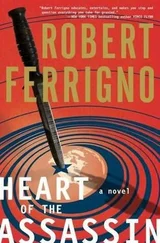

“It might not have been a crew. It might have been one man.”

Colarusso snorted. “The bodyguard was a hard-core vet with a chestful of ribbons. It would have taken more than one man to bring him down.”

Rakkim didn’t argue, exhausted, as much from the crime scene as from lack of sleep. He hoisted his drink. After the second glass, the wine tasted better. He remembered Marian in the bathtub, her hair floating around her. He remembered the stiffness of her flesh and the effort it took to get her dressed and the feel of her wet hair as he carried her. Wrestling with the dead. “I killed her, Anthony. I killed all three of them.”

“Well, that should make closing the case easier.”

“I thought I covered my tracks, but somebody must have followed me to Marian’s. I might as well have killed her myself.”

“Quit your blubbering. You want me to forgive you? I can do it. I used to be a priest.”

Rakkim stared at him.

“It’s true. I was ordained in Woodinville when I was twenty-one. Left the priesthood after the transition. I could see which way the wind was blowing…and the celibacy thing was getting to me. You think you can handle it when you start seminary, but you get out in the world and your pecker has a mind of its own. Anyway, I’m not a priest anymore, but I still got the instincts. Still go to mass every week. Father Joe there, he hears my confession…then afterwards we retire down here and he sets ’ em up. Can ’t ask for more than that from a man of God.” Colarusso leaned closer to Rakkim. “You want me to hear your confession.”

“Muslims only bare our souls to Allah.”

“You sure?”

“Well, mostly I keep my sins to myself. Allah has enough on his mind.” Rakkim was laughing…it sounded like laughter, but tears were rolling down his cheeks. “I must be drunk. I can’t keep up with you Catholics.”

“You’re doing okay.”

Rakkim finished his wine, rapped the glass on the bar for a refill. He nodded at the pool table off to one side, the green felt shiny, ripped in a couple of places, but still inviting. “I’m surprised nobody’s playing.”

“The table’s off-limits,” said Colarusso. “Last year a couple of knuckleheads got into it over a game of eight-ball, fists flying, just really tearing the place up. Father Joe had to break a cue stick over one of them.”

“Did it leave a scar?”

Colarusso grinned, rubbed the back of his head. “No, but I still get headaches.”

Rakkim watched the room in the mirror, took in the cops strung out along the bar, and was glad he had accepted Colarusso’s offer. It was a plain, dark, low-ceilinged room filled with hard cases, tough and bitter men who didn’t need the thrash and clatter of the Zone. The choirboys, that’s what Colarusso had called the regulars, although most of them weren’t practicing Catholics. Lutherans and Catholics, agnostics and atheists, it didn’t matter-sergeants and detectives and a few patrolmen, but no brass. The choirboys may not have been religious, but they were too proud to convert just for the career advantage. Dust was on the floor and photos of boxers were on the walls and a painting of Jesus with his heart pierced with thorns. The basement bar was a place to get peacefully hammered on quasi-legal wine, to sand off the raw edges of the day, one glass at a time.

“You want to tell me about those books you took from the house?” asked Colarusso.

“They belonged to Marian Warriq’s father. His private journals. There’s something in them. Some information that I need. I just don’t know what it is.”

A huge detective staggered over, draped an arm around Colarusso. The well-dressed behemoth had satiny black skin, a shaved head, and a gold stud in his nose. He glanced at Rakkim. “Didn’t you hear about the dress code, Anthony? No towel heads.” His booming laugh filled the immediate vicinity with the stink of fermenting grapes.

“Rakkim, this poor excuse for a lawman is Derrick Brummel,” said Colarusso. “Derrick, this is Rakkim Epps.”

They shook, Rakkim’s hand lost in the detective’s paw.

“I just wanted to say hello,” Brummel said to Colarusso. He shifted his eyes.

“You can say anything in front of Rakkim,” said Colarusso.

Brummel gazed at Rakkim. “Is that right?”

“Take a chance,” said Rakkim.

Brummel turned to Colarusso. “You hear about my grab-and-scram? Punk snatched a ruby ring off the finger of some businessman, grabbed it right off the street and disappeared into rush hour. I got the call, did my homework. Description matched a kid I busted a few times previous. Scooped him up the next day.” He leaned closer and seemed to bring a heat with him. “This afternoon I find out the imam of the businessman is going to try the kid under sharia law.” Brummel glanced at Rakkim. “Kid’s Catholic, Anthony.”

“That can’t be right,” said Colarusso.

“It’s true,” thundered Brummel. Heads turned along the bar. “You think I don’t know the disposition of my own case?”

“Watch your pressure, Derrick,” said Colarusso. “Sit down and have another drink.”

“Am I a law-and-order cop?” demanded Brummel.

“You’re a law-and-order cop.”

“Am I a deepwater Baptist?”

“Deep as they come,” said Colarusso.

“Then you know I’m not making excuses for this kid. He’s a thief and a loser, but no way he deserves to have his hand chopped off.”

“The Black Robes can’t do that to a Catholic,” insisted Colarusso. “No way.”

“If the businessman said he intended to donate the ring to his mosque, he might have a case,” Rakkim said quietly. “It’s a stretch, but that’s one interpretation of the statutes.”

“If the Black Robes can haul a Catholic into religious court, they can haul in anybody.” Brummel looked hard at Rakkim, the overheads reflecting off his skull. “Shit jobs, shit housing, shit treatment. Now shit law? Christians can take a lot of abuse, but at a certain point we’re going to get fed up, and then you best watch what happens.”

“I don’t like it any more than you do,” said Rakkim.

“He’s telling you the truth,” said Colarusso.

“If you say so, Anthony.”

“He doesn’t have to, I say so,” said Rakkim.

Brummel pounded Rakkim on the back. “Okay, tough guy, we’ll discuss it some other time.” A glance at Colarusso. “I’m not drunk, but I’m close enough. Time to go home and take out my troubles on the little woman.”

Colarusso and Rakkim watched Brummel leave, the bar silent, then suddenly louder as the door closed behind him.

“He’s a good cop, but he dearly hates Muslims. Probably wished he had migrated to the Bible Belt when he had a chance. Most black folks did, but he stayed behind, figured he’d give the new government a chance. I was the same way.” Colarusso sighed, exhaled the scent of overripe grapes. “You were too young to remember what the country was like before, but let me tell you, it was grim. Drugs and desperate people beating each other’s heads in for reasons they couldn’t even explain. Man against man, black against white, and God against all-that was the joke, but I sure never got a laugh out of it.” Colarusso shrugged. “Then the Jews took out New York and D.C., and it made our troubles before seem like one of those tea parties where they serve watercress sandwiches with the crusts cut off. Taught us what hard times really were. Muslims were the only people with a clear plan and a helping hand, and everyone was equal in the eyes of Allah. That’s what they said, anyway.” He was bleary-eyed. “Besides, your people are big on the punishment part of crime and punishment, and they don’t take to blasphemy. I like that. The old government actually paid a man to drop a crucifix into a jar of piss and take a picture of it. Don’t give me that look, I’m serious. He got paid money to take the picture, and people lined up around the block to look at it. So, I’m not exactly pining for the good old days, but now we got Black Robes walking into police stations like they own the place.” He shook his head. “That ain’t right.”

Читать дальше