"To the Egyptian!" Now Joseph was raising his own glass of vodka. Batsakov held up his bottle and clanked it against Joseph's glass.

"To the Egyptian!" Batsakov repeated the comment, pretending to drink from his now-empty bottle.

"Allah would be pleased!" The first officer laughed, swilling his own vodka.

That comment ignited a volvanic guffaw from within Batsakov's belly, bending him over double. "Yes, Allah would be pleased, " he said, cackling at the notion. The captain regained his composure, stood erect, and issued his next order.

"Resume course two-seven-zero. All engines ahead full!"

The Al Alamein

The Sea of Marmara

Captain Hosni Sadir watched the armed boarding party from the Turkish Navy walk across the main deck of his ship for what seemed like the hundredth time.

The Turks were an inexplicable oddity, Sadir thought. They were 98 percent Muslim. But since the 1940s, they had been allied with the Americans. Many Arab Muslims could not understand this unholy alliance.

But his Muslim brothers in Chechnya understood it.

Fear of the bloodthirsty Russians drove this alliance. The more than a quarter of a million Chechen martyrs who had gone to paradise since 1994 would approve of their Turkish Muslim brothers doing whatever was necessary to halt the expansion of Russia, even if that meant sleeping with the infidel Americans.

Sadir watched as the party, consisting of two officers and three Turkish marines, looked in crates, opened hatches, and poked around in areas where there was nothing significant. It would take weeks for such a small group to search every inch of this ship, and if they stopped every ship trying to get through the Bosphorus, they would effectively shut down one of the world's busiest shipping arteries. The economic superpowers would not let that happen.

As long as the Turks did not go below and discover the lead-walled laboratory and the silver radioactive suits waiting for Salman Dudayev's team, he had no worries. And even if they did, he still had no worries. This was Allah's mission, and he was Allah's servant.

One of the inspectors approached. "I am Lieutenant Baghadur of the Turkish Navy. Our party has completed its inspection. You are free to pass, Captain."

"A pleasure having you on board the Al Alamein." Captain Sadir accepted the Turk's salute, then watched the boarding party climb down the ladders into their patrol boats. When they were safely away at a distance of two hundred yards, he headed down the main deck to the ladder leading back up into the bridge. Thirty minutes later, Al Alamein passed north, steaming at eight knots under the first bridge spanning the Bosphorus.

The USS Honolulu The Aegean Sea

The officer of the deck, Lieutenant Darwin McCaffity, had just completed a final sweep on the scope. It confirmed a dark image of the freighter's hull against the lighter water through the periscope head window. A quick check of the side-scan sonar to confirm the ship's position showed all was ready.

"Captain, the ship is ready to vertically surface." McCaffity's voice came from just a few feet away in the dimly lit control room.

"Very well, Mr. McCaffity, " Pete said. He stood in the center of the darkened control room, watching the ship's control party maintain the seven-thousand-ton submarine completely motionless at 160 feet under the surface of the Aegean Sea.

"Commence ascent."

"Aye, sir, commence ascent."

Good plans were often as good as the paper they were written on, Pete thought, as his crew began blowing air into his sub's ballast tanks to raise her up toward the giant freighter floating just above them.

Good plans often got people killed. Especially during military operations.

Commander Pete Miranda knew of good plans gone awry. He'd attended a dozen military funerals over the years. Most involved accidents from high-risk plans that had never been tried before.

Pete wiped sweat from his forehead as his chief of the boat, Master Chief Jack Sideman, called out changes in the submarine's depth during its ascent. Sideman was serving as the Honolulu's diving officer.

"Passing one hundred feet, Captain.

"Passing ninety-five.

"Passing ninety feet."

Honolulu was executing a stealth procedure never tried or even practiced by another submarine in the history of naval warfare. This was a potential recipe for disaster.

Pete would prefer to have drilled this procedure with his crew. The efficiency and precision of a submarine in a deadly environment – and every dive into the depths of the ocean could turn deadly with one mistake by one of the hundred crewmen – was crucial. The Navy's response: Practice. Practice. Practice. The urgency of this crisis would not allow for that.

"Easy. Easy. Bring her up slow and easy, Mr. COB, " Pete said.

The procedure that they were attempting was delicate and dangerous.

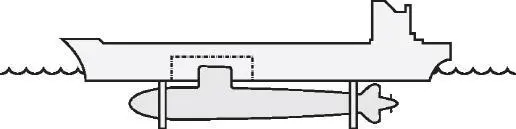

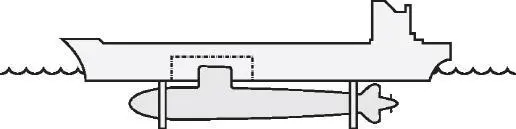

Hovering underneath the Aegean Sea at a depth of ninety feet, just below the freighter Volga River, Honolulu was blowing incremental amounts of compressed air from her air flasks into her ballast tanks. This tedious process was making the sub just slightly lighter and bringing the top of her sail closer to the bottom of the drifting freighter.

The Honolulu was 360 feet long. The Volga River at 1065 feet long and weighing over sixty tons was a giant in comparison. Because of Volga River's size, an ascent that got out of control had the potential to reek havoc on the submarine, like facing the punch of a heavyweight boxer.

A mistake could sink the submarine.

Pete glanced at the docking schematic devised by Naval engineers back at Newport News. It was mounted on a table next to his position.

The plan was to raise the sub gently through the water, inch by inch, until finally, the top of the submarine's sail surfaced into the mammoth watertight compartment that had been cut into the ship's hull.

One problem was movement by the freighter. The Volga River had disengaged her propellers, but she was not entirely still in the water. All ships, even the mightiest aircraft carriers and the largest oil tankers, were prone to drift in the sea.

The process of docking a 6100-ton submarine with a 40, 000-ton surface ship left no room for error.

If the ascent through the water was off even just a few feet, the submarine's sail could collide with the keel of the freighter. If the ascent was too rapid, a collision could threaten the watertight integrity of his sub. But the danger that Pete feared the most were the huge titanium O-rings that were mounted by Naval engineers under the bow and stern of Volga River.

In theory, if Honolulu could surface into the open space in the bottom of the freighter, the O-rings would then slowly collapse inwardly along a mechanized track until they gently caressed the bow and stern sections of the submarine. Once in place, they would serve as a giant cradle in which the sub would rest on its transit under the freighter through the Bosphorus.

Should the sub miss and strike one of those O rings at too fast of a rate… Well, no skipper wanted a giant underwater hatchet taking a hack at his boat. Such a disaster might just send Honolulu to the bottom.

This was all compounded by the problem of murky visibility. Submarines do not have windows so that captains can look out and simply drive the ship to some point under the water. And even if they did have windows, the darkness in the depths of the sea would leave a submarine skipper like Pete Miranda staring into a black abyss.

Like an airplane flying through thick cloud cover in the middle of the night, submarines operating under the sea rely totally on instruments for navigation. For her eyes, Honolulu used active and passive sonar to determine what objects might be in the water around her. GPS was used to determine the sub's exact latitudinal and longitudinal coordinates on the earth. Active sonar shot a very loud ping through the sea that could be heard for miles away and could be heard by warships operating in the area.

Читать дальше