The molecular biologist buried himself in his work on Rebecca’s protein chemistry. Underneath the clamshell, hardly noticing the deteriorating weather, he rarely moved from the small laboratory he had created for himself. Completing separations, isolating DNA, staining gels, analyzing spots and blots, performing optical density calibrations, and compiling data — it all helped to detach him from the horror of what might occur. At the same time the irony of the situation was not lost on him. There he was, devoting himself to the general cause of discovering man’s origins, while not eight hundred kilometres away, man was apparently set on destroying his own future.

He felt grateful for the literal isolation and separateness of what he was doing. Purifying high-quality plasmid DNA to an absolute minimum. Separating DNA from RNA, cellular proteins, and other impurities. There was no doubt about it: Molecules were a great way to keep your head together. And molecular phylogeny, as the drawing of evolutionary family trees from biochemical data was called, was as much of a sanctuary as the glacier on which the clamshell was erected.

Despite the fact that he was working in one of the most inaccessible places on earth, Warner was equipped with the very latest biochemical hardware and software. The techniques he was using were a thousand times more sophisticated than those that had been available to Sarich and Wilson, Berkeley’s two wunderkinds of molecular anthropology, back in the sixties. Warner’s work involved analyzing not just nucleotide sequences but the yeti’s DNA structure itself. He had more faith in the idea that whole genome DNA changed at a uniform average rate than any serum albumins. DNA hybridization was a technique that involved the analysis of not just one blood protein or gene, but all of an organism’s information-carrying genetic material.

Generally speaking, Warner had no argument with the results Sarich and Wilson had found with regard to the DNA differences between apes and human beings. He still remained impressed by the simple fact that the chimpanzee, the gorilla, and man shared ninety-eight-point-four percent of their DNA. But unlike Sarich and Wilson, he assumed a more distant divergence between man and apes, at around seven to nine million years ago. And he had his own view of man’s evolutionary tree.

The standard version in most textbooks depicted the human line as something separate from the common ancestor of the gorilla and the chimpanzee. The molecular evidence as argued by Sarich and Wilson, however, placed man, chimp, and gorilla together, with no human ancestor that was not also an ancestor of the chimp and the gorilla. Lincoln Warner had argued, however, that humans were once possessed of more than one kind of DNA, and that the human species had enjoyed a double origin: African and Asian.

Now, as he faced the UV image of Rebecca’s DNA on the colour monitor, adjusting the brightness, and performing edge enhancement with his mouse, things were looking very different from what he had imagined. So different that at first he thought he must have made a mistake and went back to rim the whole gel documentation program again, to make doubly sure of his results. Satisfied at last with the image, he clicked the mouse, storing the final picture on the hard disk, and then ordered up a thermal print for his notes.

He was going to need a little time to consider the implications of what his DNA analysis had shown. Meanwhile, he fed the data into the Phylogenetic Analysis and Simulation Software program to see what the computer itself might extrapolate from his apparently extraordinary discovery.

The threat of nuclear war seemed to herald a storm as bad as any of the old Himalayan hands — Mac, Jutta, and the sirdar — could remember. The temperature dropped while the wind, reaching speeds of well over a hundred and sixty kilometres per hour, howled through the Sanctuary as if in homage to the larger, man-made energy that might at any time be unleashed upon the whole subcontinent. Even the clamshell groaned and shook under the force of the wind, making its human occupants ever more nervous and irritable.

By the third morning of the storm, in whiteout conditions that made even the shortest walk between the clamshell and the hotels hazardous, relationships among the expedition team were strained to the breaking point.

‘Hoo-hooo-hoooo-hoooo!’

Cody, who was recording all of Rebecca’s sounds, nodded appreciatively and turned off his machine.

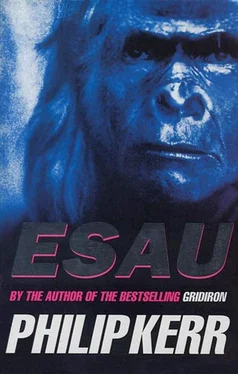

‘You know, Swift, Rebecca has over a dozen different kinds of sound,’ he said. ‘And that doesn’t include her vocalizations. If we had another adult we might actually be able to record them all in detail. And if I had a more powerful microphone than the thing on this Walkman, I might be able to pick up some of the noises she makes to Esau.’

Nursing Esau, Rebecca would frequently cuddle him and emit a number of whispered sounds into his face. But sometimes she moved her lips as well in a simulacrum of human speech, and it looked to everyone as if she might be talking to her baby.

‘Jesus, listen to him,’ grumbled Boyd, staring at the game of solitaire he was playing on his laptop computer. He did not find Cody’s enthusiasm for the yetis the least bit infectious. ‘He wants two of these monsters. As if it doesn’t smell bad enough in here already.’

Swift was about to offer some caustic remark at Boyd’s expense and then checked herself, realizing that for once she agreed with him. Rebecca had developed diarrhoea, and despite the fact that the squeeze cage was cleaned several times a day, the smell was sometimes overpoweringly bad.

‘What do you expect an Abominable Snowman to smell like?’ laughed Mac, who was busy labelling his films.

Jameson, reading a book, looked up and said, ‘She can’t help it.’

‘The rest of us go outside,’ persisted Boyd. ‘Why can’t she?’

‘As soon as her stitches are healed,’ said Jameson, ‘we’ll have to let her go. But until then we owe it to her and to Esau to keep a close eye on them. After all, they didn’t ask to be captured.’

‘When will that be?’ demanded Boyd.

Jameson looked inquiringly at Jutta.

‘Perhaps tomorrow,’ she said.

‘Hoo-hoooo-hooooo-hooooo!’

Boyd left his game of solitaire and began to pace around the cage.

‘I think I’ll have gone crazy by then. Can’t you tell her to shut up? I thought Jack said that the yetis knew sign language. I mean, what’s the sign for shut your goddamn mouth?’

Jack swung his legs off the camp bed and sat up slowly.

‘They do sign,’ he said. ‘I saw them.’

‘Oh, I don’t doubt it,’ said Cody, his enthusiasm undiminished by Boyd’s ill-tempered remarks. ‘I’ve tried to sign to her but without success. I expect it’s just that the signs she knows belong to a different convention, that’s all.’

He put down his tape recorder and stretched wearily.

‘I guess that’s enough for one day,’ he said, and collecting his well-thumbed paperback copy of Seven Pillars of Wisdom, he returned to Lawrence and the revolt of the desert.

Boyd stopped his pacing and began to search for something in his rucksack.

Swift stood up from the circle of chairs grouped around the cage and went to sit beside Jack.

‘How are you feeling?’ she asked him.

‘A lot better, thanks. You know, Boyd’s right. It does stink in here. I don’t think I’ll ever get the stink of them out of my nostrils.’

‘That’s for sure,’ said Boyd. Glancing around the clamshell, he saw that nobody was paying Rebecca any attention. Cody was now deep inside his book. Warner was working on his desktop PC. Jutta was listening to some music on her Walkman. The sirdar was looking at an old magazine and drinking a cup of his disgusting brew. Boyd nodded to himself: This was the opportunity he had been waiting for. He stepped closer to the cage and almost absently began to pass the small electronic box he had collected from his rucksack up and down the fur on Rebecca’s back. About the size of a photographer’s light meter, the device was a radiometer, a sophisticated kind of Geiger counter. On the lowest range setting, the radiometer was picking up a very small reading from Rebecca’s fur, as if she might have come into contact with something radioactive. He put his arm through the bars of the cage, bringing the radiometer as close to Rebecca’s hands as he dared. This time the needle flickered significantly.

Читать дальше