‘Now we know what happened to Didier’s ring,’ she said with a smile, before adding, ‘but I don’t think he’d mind. She’s beautiful.’

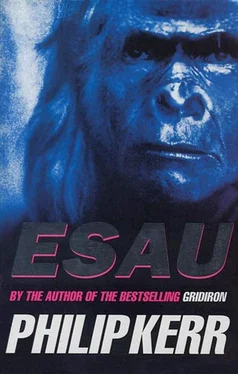

Cody agreed, following her around the table. ‘Isn’t she? She’s the classic ape somatotype — a little like a gorilla-sized orang. Bigger than a gorilla, of course. But that face. It’s a much more human-looking physiognomy. This ape has a proper nose, with none of the outstanding nasal troughs that characterize a gorilla’s features...’

Cody hesitated to step in front of Mac’s camera lens.

‘Keep talking, Byron,’ said Mac. ‘I’m getting all this on videotape.’

Jutta glanced over her shoulder at Mac and his video camera and said, ‘I wouldn’t stand there if I were you, Mac.’

‘Why the bloody hell not?’ Mac frowned. ‘This is going to be an important film of record. Byron’s first thoughts about the snowman could be important. I’m not in your way.’

‘No but—’

‘Still not—’

Jameson had been about to tell Jutta that he thought the baby’s head was still not engaged in the yeti’s pelvis when suddenly a large quantity of amniotic fluid, the so-called birth waters, made a dramatic exit from the still anaesthetised creature’s vagina, drenching Jameson, Jutta, Mac, and Mac’s camera.

Having anticipated some kind of membrane rupture, Jutta was able to ignore what had happened and immediately check the yeti’s cervix, which she found was now fully dilated. But soaked from head to foot, Mac was beside himself with rage and disgust, much to everyone else’s amusement.

‘That’s just bloody great,’ he bellowed. ‘Look at me. I’m covered in this shit.’

‘I told you not to stand there,’ murmured Jutta, amid general guffaws of laughter. She glanced at Jameson.

‘Can you see any meconium in the fluid?’

Jameson nodded. ‘Some,’ he said, and placing the ends of his stethoscope in his ears, he listened once again for a heartbeat. ‘Seems rather slower than it was.’

‘—like something out of Alien,’ grumbled Mac, wiping down his camera.

‘You’re lucky it wasn’t outside,’ said Swift. ‘Or you’d now be frozen solid.’

The yeti moved its head, prompting Jameson to administer another, smaller shot.

‘She’s going into the second stage of labour,’ he said. ‘Last thing we need now is for her to regain consciousness.’

‘Not to mention the use of those arms,’ said Cody. ‘Probably she’d kill us and then kill her baby.’

‘How’s she breathing?’ Jameson asked Jutta.

The German checked the resuscitation bag.

‘Normal.’

Jameson checked the baby’s heartbeat once again.

‘Slower still,’ he said. ‘You were right, Jutta. It’s looking very much as if we’re going to need those spoons after all.’

Like Boyd, Swift too had never seen any kind of birth, except on television, which somehow hardly counted. Watching Miles Jameson and Jutta Henze as they helped to deliver the yeti baby, she thought it was probably not so very different from human birth. There was even the guy with the video camera getting it all on tape for posterity, like a proud father. But she had not expected to feel quite so emotionally involved in the spectacle. She wondered if they all felt the same.

Lincoln Warner was pacing up and down the clamshell, looking for all the world like an expectant father. Hurké Gurung and Ang Tsering were nervously smoking cigarettes in the airlock doorway and keeping their distance. The yeti labour looked distinctly human to them, and therefore something from which they would normally have been excluded by the women. Byron Cody was standing a short distance away from the delivery table, his arms tightly folded in front of his chest, as if he didn’t quite trust his hands to behave calmly. Even Boyd, his scepticism gratifyingly silenced, was chewing his fingernails anxiously.

A forceps delivery. Swift knew the phrase to mean something hazardous, with a greater risk of damage to the baby, as well as the considerable risk to the mother. As Jameson confirmed the position of the baby’s head with his fingers and prepared to insert the first cup of his makeshift forceps. Swift discovered she could hardly bear to watch.

Miles Jameson had never used a pair of forceps before, let alone a pair that had been improvised from a Himalayan kitchen. At the Los Angeles Zoo he’d been involved in the births of many animals, even done a couple of cesarean sections with some of the more valuable specimens, but what he was now doing seemed uncomfortably similar to the birth of a human baby. He kept wishing he could cede control of the labour to Jutta, but she told him that he was doing fine and that she would make a midwife out of him yet.

Gently he guided the first spoon alongside the baby’s head, using his fingers to check that it passed smoothly and easily between the head and the side wall of the yeti’s vagina. Then he inserted the second spoon, and only when he was satisfied that the cups of the spoons were correctly applied did he gather the two handles together.

‘Here goes,’ he said. ‘Are you ready with those scissors?’

‘Ready,’ said Jutta, snipping the air attentively.

Slowly, Jameson started to pull, maintaining traction for about thirty seconds, after which he relaxed for a moment and then began again. Each pull brought the baby’s head lower down the yeti mother’s pelvis until eventually the perineum was distended and Jameson ordered Jutta to perform the episiotomy. Jutta stepped in to the table and began to cut.

The muscles of the yeti’s perineum were so strong that they were almost rigid, and Jutta had to use every ounce of strength in her forearm to close the sharp scissors on them. Nevertheless the operation was quickly performed and the perineum neatly incised in the mid-line. As soon as Jutta finished cutting, Jameson was able to extend the baby’s head on its neck so that its small and wrinkled face could extend over the vaginal wall and the perineum.

‘Here comes the head,’ he said.

Immediately he removed the forceps, and having cleaned the baby’s nose, mouth, and eyes with a sterile swab, he set about aspirating the throat and mouth with a small piece of plastic tubing that had been improvised from Jack’s discarded SCE suit.

Boyd watched him spit several times on the floor and grimaced. ‘I don’t know how you can do that. Jesus, it spoils my dinner just watching you.’

‘We’re almost there now,’ said Jameson, hardly conscious that Boyd had said anything.

‘Nobody’s asking you to watch,’ Swift said irritably, suddenly feeling a powerful sense of sorority with the labouring female in the face of such stupid male disgust. ‘You’re the one who said this was just a hallucination, remember?’

‘You’re right,’ said Boyd. ‘I was out of line, I admit it.’ He smiled amiably. ‘Hey, I’m just glad she’s not a single mother, y’know?’

Swift looked puzzled.

‘I mean, she’s wearing a gold ring,’ explained Boyd. ‘How come?’

Swift explained what had happened to Didier Lauren and how the yeti must have taken the ring from his dead finger.

‘Primates have a fascination for shiny objects,’ added Cody. ‘In that respect they’re just like children.’

‘Is that so?’

The rest of the delivery was easy, and minutes later, Jameson laid the yeti baby on the still sedated mother’s abdomen. Already breathing normally, the baby lay there and twitched a little, its head looking distinctly pointed, and its thick hair plastered down onto its body by the vernix. Gradually as the blue skin colour disappeared, the baby grasped its mother’s fur with two small fists, and grimacing angrily, it uttered a short cry.

Читать дальше