‘There’s a small Buddhist temple at Pangboche,’ he explained. ‘In the foothills of Everest. For a few rupees, the Lama will show you what is claimed to be the scalp of a yeti. And also at Khungjung, in the same area. That’s three hundred kilometres away. But if things don’t work out here...’

The shelf rose steeply in front of him and bent sharply to the right. Steep enough to require the aid of handholds, maybe even a few ice screws. On one side the wall was completely smooth, while on the other, there was just the chasm disappearing into the darkness below. With his ice axe he struck at the floor of the shelf and found the chrome molybdenum head bouncing off rock-hard ice. The wall proved no less durable. He tried to hammer in an ice screw, and then a peg, but with no result.

‘Looks like I’m going to have to climb some,’ he said. ‘Only I’m damned if I can see how. I’ve never seen ice this hard before.’

Sliding the axe beneath his belt and returning the hammer and screw to his backpack. Jack reached forward and ran his hands up and down the wall. Finally he found something. Between the sloping floor of the shelf and the wall was a gap of about five centimetres. Just enough room to employ the same sophisticated mountaineering technique he had used to get up the National Geographic building. Called laybacking, the technique involved bending forward, holding on to the narrow underside of the wall with the tips of his fingers, and then climbing up on the very points of his crampons.

‘I’ll say one thing for those hairy guys,’ he grunted as he tried to climb in a series of fluid, continuous movements between one resting place and the next. ‘There’s nothing wrong with their mountaincraft. Of course, getting back down this little slope... is going to be... even more fun than climbing up.’

Turning the corner he reached the top, panting after his great effort, and an extraordinary sight now met his eyes.

He was standing at the beginning of an enormous cavern whose icy walls rose far above his head and dimly reflected the light from a distant disc of blue sky. About a hundred metres across an assault course of medium-sized ice blocks and mini fissures was the cavern’s exit, an enormous portal of ice whose windblown shape resembled a eighteen-metre-high figure eight. Beyond the portal was a remarkable scene: A strange gigantic company of pinnacles rose, gleaming white in the late afternoon sun and enclosing, like some smaller, more exclusive sanctuary, not white ice, but snowy green.

‘I’ve found something,’ he told the others. ‘I must have come out on the other side of the Sanctuary, on the eastern side of Machhapuchhare.’

He stepped from one block to another. Like a beachcomber crossing the rocks on a seashore inlet, and finally stepped onto a floor strewn with loose moraine — the debris carried down and deposited by the glacier — upon which an inadequate path had already been stamped. Sensing some new discovery, he started to walk quickly toward the cavern’s legendary-looking exit.

‘There’s a tiny valley here. No more than about one and a half square kilometres. And hidden by a small circle of peaks. It looks incredibly well sheltered. There seems to be vegetation. Yes. This is fantastic. I wish you could see this. I’ve never seen anything quite like it.’

Emerging from the figure-eight exit, he found himself at the edge of a dense forest of pine trees and giant rhododendrons. He had heard of such high-altitude forests in other more remote countries bordering Nepal, such as Sikkim and Zanskar, but not in this particular part of the mountains. There were times when Jack thought he knew all there was to be known about the Himalayas, but this was not one of them. Full of wonder at what he could see, he tiled to describe the sight on the radio.

‘There’s Himalayan silver fir, birch, juniper trees, and some coniferous shrubs I’ve never seen before. And the rhododendrons are just incredible. I’ve seen them ten metres high. But these must be fifty. Densely packed too. This looks more like rain forest than an Alpine zone.’

He glanced up at the sky, the photochromic plastic in his helmet darkening in the sunlight, and caught sight of a large bird of prey — a Himalayan vulture, he thought — as it wheeled high above the valley, searching for food.

Something scampered across the ground near his feet. A small mouse hare, almost tame.

‘There’s animal life here too. I just saw a rabbit. If the yeti has a natural habitat, I’m certain this just has to be it. Swift, this is it.’

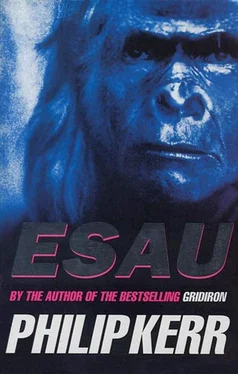

‘Jack, this is Byron. I hate to be a party pooper, but once again I advise extreme caution. If this habitat is as much like the rain forest as you say, then it might be best to suppose that yeti will behave like any mountain gorilla. Blundering through tall vegetation in that space suit could be very dangerous. Especially if the yetis have any young ones with them. Also if the yetis have learned to treat man as an enemy, then it might be safer to assume that they will defend their habitat aggressively. Jack, on no account should you try to find a nest. Mountain gorillas commonly post sentries to keep a lookout for the rest of the group. The chances are that they’ve probably seen you already but won’t react unless you look like you’re about to pose an immediate threat.’

‘Whatever you say, Byron, you’re the expert. Only it seems a shame to go back now, having come so far.’

‘Just bear Hurké Gurung’s experience in mind.’

‘Good point.’

A whistle, as loud as any construction worker’s, echoed through the forest, as if simultaneously confirming what Cody had said.

‘Did you hear that?’ Jack asked.

‘We heard it,’ confirmed Cody. ‘Now get the hell out of there.’

‘On my way.’

Reluctantly, Jack turned to go back the way he had come. Not that it would have been easy to go any farther anyway. The rhododendron forest looked so impenetrable that he would have needed a jungle knife — a khukuri — to hack his way through it.

Another whistle, louder this time. Did that mean a yeti was coming closer? No matter. He was going anyway. Already he was stepping on to the medial moraine that led back into the ice cavern.

He glanced down at the control panel. Eight hours of power left. More than enough to make it back up to the surface. Hearing a rustling sound. Jack felt his heart stir uncomfortably inside his chest, as if protesting its unease, and he turned to face the forest again. There was movement in the giant rhododendron bushes, and for the first time since his arrival on the edge of the forest he felt alarm. Now he was glad that he had taken Cody’s advice. It would have been foolish to have gone blundering into the forest. Jack turned on his heel, and hearing what might just have been the sound of chest beating, he carried on walking with quickened footsteps. Alarm was being overtaken by fear now. The sooner he was out of there, the better. The next time he came he would bring Jameson and a gun and a net. Several guns probably.

Another chest beat. Like the sound of coconuts tumbling out of a sack and onto the ground. Or a big drill working on a distant wall. Once again he picked up his pace. He was almost running now. Stumbling a little on the loose moraine — the crampons were not suited to this kind of terrain, and he knew he should have removed them — he glanced down at the ground to check his footing. And as he moved a little farther away from daylight, the carbide lamp on top of his helmet switched on automatically, illuminating the high ceiling and a roaring demon hurtling toward him out of the darkness of the cavern ahead.

Jack heard someone yell ‘Shit,’ and then groaned as the collision knocked all the breath out of his body and carried him backward onto the ground, like the most powerful football tackle imaginable. A sharp stabbing pain in his ribs was followed by a more protracted torment as the tornado of arms and legs mauled him powerfully for about ten or twelve metres back across the floor toward the forest, and then something bit him hard. The last thing he was aware of was being wrestled through the rhododendrons and down a short gradient, and then another excruciating flash of teeth.

Читать дальше