‘I figured it must be something trivial.’

‘What about this Furness character?’ Perrins asked. ‘Do you think we might recruit him?’

‘Possible, I suppose. He did a TV commercial for junk bonds once, so he can’t be too highly principled.’

‘What about her?’

‘That I couldn’t say. She’s Australian or English or something.’

Perrins leaned across the desk and pressed a switch on his intercom.

‘Connie. Would you get me the files on—?’ He glanced down at the grant proposal and read the two names on the cover. ‘On a Jack Furness. F-U-R-N-E-S-S. And a Dr. Stella Swift, as in the bird, of the University of California in Berkeley. Oh, and ask Chaz Mustilli if he’d like to come and see me in my office. Thanks, Connie.’

Releasing the switch, he turned the pages of the grant proposal and perused the mission statement.

‘Human fossils, huh?’

‘Paleoanthropology,’ nodded Brindley. ‘Haven’t you heard? It’s the new religion.’

‘People have got to believe in something,’ shrugged Perrins. ‘But speaking for myself I can’t imagine a God who would prefer going to church to seeing a movie.’

‘Let’s stay in tonight,’ said Swift. ‘Let’s have dinner in the hotel.’

She was watching the television news.

‘But we had dinner here last night,’ objected Jack. ‘Wouldn’t you prefer to go somewhere different?’

‘I’m not in the mood for different. I’m in the mood for staying in and feeling sorry for myself.’

‘Okay, if that’s what you want.’

‘Shit. Wouldn’t you just believe it?’

‘What?’

Swift pointed at the television.

‘The news,’ she said dully. ‘The secretary of state has managed to persuade the Indians and Pakistanis to agree to a three-month cooling-off period.’

‘What’s wrong with that?’ demanded Jack.

‘Nothing,’ shrugged Swift. ‘It’s just that three months would have been a very convenient window for us to have gotten safely in and out of Nepal.’

‘Most expeditions, it takes at least three months to put them together,’ said Jack.

‘This isn’t most expeditions. At least not anymore.’

She kissed him on the cheek.

‘I’m going to take a bath. Jack.’

‘Can’t I stay and watch?’

Swift laughed a silent, embarrassed laugh. There were times when he came on like a high school kid. But since starting to sleep with him again, she had begun to realize how much she had missed him in the first place.

‘Why don’t I join you in the bar?’

‘I could use a drink,’ he admitted. ‘I hate committees.’ He shook his head angrily. ‘I still can’t believe they turned us down.’

‘You’re just saying that. You warned me it might be tough.’ Swift shrugged bravely. ‘Anyway, it’s me they turned down. Me and my idea. They didn’t turn you down. They said you can go back and finish climbing the rest of the peaks, if you want.’

‘That’s not what I want. Not anymore.’

‘Well then, there’s still the National Science Foundation. Warren Fitzgerald’s on the peer review committee. He’s dean of paleoanthropology at Berkeley.’

‘It’s not what you know, it’s who you know, huh?’

‘Actually, it’s who you sleep with.’

‘You’re kidding.’

She laughed. ‘Just a bit. Unfortunately I think the National Science people are just as tight for cash right now. So Fitzgerald told me anyway.’

‘We’ll find the money somehow. We have to. Maybe a newspaper or a television network. There must be many people who would want to get involved with something like this. Maybe if we levelled with them and told them what the expedition was really all about...?’

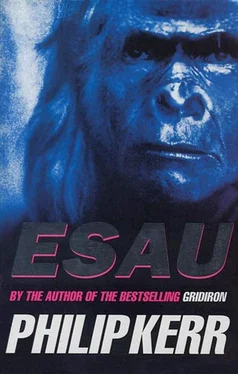

‘No way,’ Swift said firmly. ‘The last thing we want is a lot of media interest before we get started. We have to stick to the original plan and keep the idea of a living Esau under wraps. Okay?’

‘Yeah. You’re right.’

Swift nodded and then headed toward the bathroom.

‘I’ll see you downstairs.’

The Jefferson’s lounge looked like the drawing room of an eighteenth-century house. Above a green-and-white marble fireplace, where a large log was burning noisily, was a portrait of Thomas Jefferson and his racing dog, a white whippet, sniffing at its master’s declamatory hand.

Jack sat down in a large armchair, ordered a whisky from the waiter, and settled back to enjoy the fire. The windows rattled against the howling wind, and for a moment he thought he could have been back in the Himalayas. On such a cold night he was glad after all to be staying indoors. The widely praised Virginian cooking of the hotel chef was exactly what he wanted. When his drink arrived, he nursed it for a while, drank it, and then ordered another, wishing he’d brought something to read. Swift had a habit of staying in the bath too long. Most women did.

‘Mister Furness?’

‘Hmm?’

Jack looked up from his study of the firelight. The man standing over him was tall and dressed in a conservative-looking blazer that seemed slightly too big for him, although he appeared in excellent shape.

‘I hope you’ll pardon the interruption, sir,’ said the man, and pointed to the other armchair. ‘May I?’

Jack nodded and then read the proffered business card.

‘ “Jon Boyd, senior director, Alpine and Arctic Research Institute.” What can I do for you, Mister Boyd?’

The waiter returned with Jack’s drink. Boyd handed him his credit card, ordered a daiquiri, and told the waiter to put both drinks on his tab. Then he stretched his hands toward the fire. Jack caught sight of an impressive-looking tattoo. With his buzz haircut, square jaw, and short moustache Boyd reminded Jack of the gay clones you could still see in San Francisco’s Castro district. Apart from the blazer. That looked like off-duty military.

‘The trouble with wood is that there’s not much heat in it,’ he grumbled, then abruptly changed gears. ‘Frankly, I was hoping that you might be able to help me.’

‘Oh? And how might I do that?’

‘I’m a geologist,’ explained Boyd. ‘But for a while now, climatology’s been my thing. Do you know anything about climatology, Mister Furness?’

‘In my line of work, it can save your life if you know something about weather,’ said Jack. ‘It’s a constantly recurring theme in the conversation of most mountaineers, I’m afraid. You learn to blend a little theoretical knowledge with a lot of real-life situation. But mostly it’s a question of listening to weather reports on the radio. I’m an expert on listening to those.’

‘Is the term “katabatic” wind familiar to you?’

‘It’s a wind that develops when air cooled on high ground becomes dense enough to flow downhill, right?’

‘Exactly so.’

‘I know enough about them to avoid camping in valley bottoms and hollows if I want a comfortable night,’ said Jack.

‘On the Antarctic plateau, these winds can reach tremendous speeds,’ said Boyd. ‘As a result they often remove recently fallen snow. Which is where I come in. Snow and ice. You see, my special field of inquiry is the climatic factors that affect the preservation of snow.’

The waiter returned bearing their drinks, and there was a moment’s pause as each man contemplated his glass.

‘Snow?’ Jack tried to sound interested, but he was beginning to regret his tolerance of this stranger. He was beginning to feel a little imposed upon. ‘Why would anyone want to preserve snow?’

‘Snow and ice. In particular, the effect of global warming on the great ice sheets.’

Jack groaned inwardly. An ecology freak. Just his luck. Where the hell was Swift?

‘Most of our work has been done on the Antarctic peninsula and islands. We hope to understand the outcome of the threatened runaway greenhouse effect. Frankly, there’s a lot of conflicting information. The Greenland ice sheet is thickening. And there have been increases in the amount of snow at the poles. Yet the climate continues to indicate that the melting of ice is accelerating.’

Читать дальше