‘Okay.’

‘Just as long as we understand each other, right?’

‘Right.’

‘’Cause I’m not in the mood.’ His penis had thickened and he started to grin at her. ‘I don’t suppose you’d care to doggylock before breakfast?’

‘I think you should have that shower,’ she said. ‘And you’d better make it a cold one.’

Jack finished his ham and eggs, drained his coffee cup noisily, and eyed the laptop poking out of her shoulder bag with continuing suspicion. But showered and shaved, and wearing a clean shirt and jeans, he already looked like a different man. Now he sounded like one, too.

‘I feel a lot better for that. Thank you for a delicious breakfast. And I appreciate your coming over here. I’ve kind of let myself go these past few days.’

‘How much did you have?’

‘Whisky? Just the one bottle.’ He gave a sheepish sort of shrug. ‘Never did have much stamina as a drinker.’

She nodded, awaiting the right moment to broach the subject that now concerned her. She sat back in her chair and lit one of his cigarettes. For a moment she pretended to be distracted by the sound of a couple of jays squabbling in a tree outside the kitchen window. Then she said:

‘So how were the people at National Geographic?’

‘Oh you know.’ He shrugged. ‘Bureaucratic. Chiseling about a few thousand bucks I paid out in compensation to the families of the Sherpas who were killed. Can you believe that?’ He shook his head and sighed sadly. ‘Lousy bean counters.’

‘You didn’t fall out with them, I hope?’

‘No, I didn’t fall out with them.’

She had spoken too quickly.

‘Why?’ he added, frowning. ‘What’s it to you?’

‘Jack. Don’t be so defensive. They’re your principal sponsors, aren’t they?’ She shifted uncomfortably in her seat. ‘I just don’t think that you should alienate them for no good reason. It’s the bean counters who run everything these days. You might as well get used to the idea.’

‘If you say so.’

Swift folded her arms and went over to the window, feeling it was still too soon for her to come to the main object of her mission. ‘I love it here,’ she said quietly.

‘If you say so.’

‘And now what are you going to do?’

‘I’m going to have another cup of coffee.’

‘I meant, what are your plans. Jack?’

‘Rest up a while. Then I dunno. I guess go back and finish the peaks. Solo, I suppose. Trango Tower looks tough enough.’

‘You don’t sound very sure.’

‘What do you want me to say?’ His eyes narrowed again. ‘That’s what this is all about, isn’t it? Whatever it is you’re up to.’

‘Jack. What are you talking about?’

‘The real reason you came.’

Swift stamped her foot angrily. ‘Can’t I just do something for you without you thinking I’ve got some ulterior motive? Jack? Why do you have to be so bloody suspicious?’

‘Because I know you. Mother Teresa you are not. It has something to do with that damned fossil, doesn’t it?’

Swift said nothing, pretending to sulk. This was not going the way she had expected.

‘Well, doesn’t it?’

‘All right, yes it does,’ she snapped.

Jack grinned. ‘That’s my girl.’

He leaned forward on his chair, took her by the hand, and pulled her back to the kitchen table.

‘Now, why don’t you sit yourself down and I’ll try not to look up that abbreviated skirt you’re almost wearing while you tell me exactly what it is that you want?’

She sat down, facing him, knees pressed tight together, and smiled. Then quickly she opened and closed her legs as if teasing him and laughed.

‘I think it’s a new type specimen,’ she said excitedly.

‘That’s good, huh?’

‘It’s wonderful.’

She collected her Toshiba from her bag, set it on the table, flipped up the screen, and switched it on. The laptop whirred like a tiny vacuum cleaner and began to emit a quiet scraping noise as it started up a CD.

‘A type specimen is a kind of flagship for a new species, a fossil against which any similar fossil material will have to be compared. It’s what every paleoanthropologist dreams of. Jack. Eventually, I hope, there will be a formal citation that will include the species name or number, and the associated author — me. But everyone will know the fossil by its popular name. I mean no one ever talks of skull 1470, everyone talks of Lucy.’

Jack nodded. ‘I’ve heard of Lucy.’

‘I’m going to name this one after you. Jack. With your permission.’

‘Jack? Doesn’t sound right somehow.’

‘No. That’s not what I meant. Do you remember what some people called you at Oxford, because you’re so hairy?’

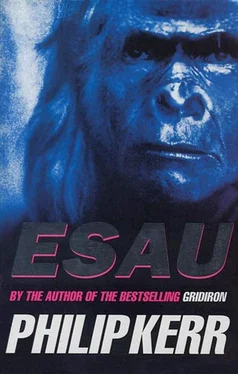

‘Sure. They called me Esau.’ He nodded. ‘Esau. I kind of like that. Sounds much more appropriate for an ape-man.’ He shrugged. ‘That wasn’t so difficult, now was it? Hell, you ought to have known I’d say yes. Why should I object? I’m honoured.’

Swift shook her head. ‘There’s more.’

‘Oh?’

‘I want you to help me work on a grant proposal for the National Geographic Society. To put together an outline for a plan to survey the Annapurna Sanctuary and explore some of the caves in search of paratypes and referred material. In short, I want you to be the official leader of an expedition to look for fossils that might be related to Esau.’

‘Me? I’m no anthropologist.’

‘True. But you do know the Himalayas and the Sanctuary better than any other American.’ She paused. ‘Besides, that shit’s only for the grant proposal. In reality I want us to take an expedition to go and look for something rather better than a few bones.’

‘Like what for instance?’

‘According to Stewart Ray Sacher — he’s in charge of geochronometry at Berkeley — the skull doesn’t carbon date. In other words, it’s less than a thousand years old. He says that the reason for this is that the corpse must first have been in a glacier for at least fifty thousand years, and that only when the glacier melted did Carbon-14 decay begin. Warren Fitzgerald thinks it must have been a lot longer. Maybe a hundred or a hundred and fifty thousand years.

‘But the question I’ve been asking myself is why assume it’s older when vow can just as easily assume that it’s younger. Let the fossil speak for itself, that’s what Sacher says. Except that he won’t. But what I reckon is this: Why not consider the possibility that it is less than a thousand years old? I say, why not consider the possibility that the skull may indeed be exactly what it seems to be? Something that may not be a fossil at all.’

Jack frowned. ‘Wait a minute. I’m confused. Let the fossil speak for itself, you said. But now you’re saying that this may not be a fossil at all?’ He shrugged. ‘Well, which is it?’

‘Okay, now the prefix Palaeo comes from a Greek word meaning ancient. I think that’s the part that may be irrelevant here.’ She shrugged. ‘I guess that’s all I’m saying really. We dump the ancient part.’

‘Of course, you mean more than you say. And you know it. So how about you stop bullshitting me and come to the point?’

‘Okay. Here’s my idea. Jack. What if this skull is recent? So recent that we could go to the Himalayas and find not some bones but an actual living fossil?’

‘You mean like a dodo?’

‘Not exactly. The dodo is extinct. I mean we should go and find something we never knew existed in the first place. A new species.’

‘A new species.’ Jack frowned as he considered the idea. ‘At that kind of height? You have to be kidding. The only new species you might find up there is a mutant strain of cold virus.’

Читать дальше