He sighed. Well, he’d known it would be a long shot. What’d they have? A vague computer drawing, a possible eye condition, a possible habit, a grudge against a prison guard.

What else should the -?

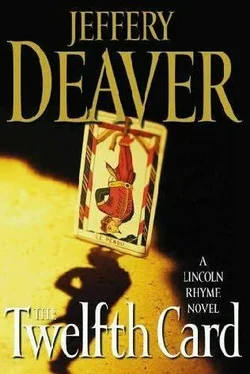

Rhyme frowned. He was staring at the twelfth card in the tarot deck.

The Hanged Man does not refer to someone being punished …

Maybe not, but it still depicted a man dangling from a scaffold.

Something clicked in his mind. He glanced at the evidence chart again. Noting: the baton, the electricity hookup on Elizabeth Street, the poison gas, the cluster of bullets in the heart, the lynching of Charlie Tucker, the rope fibers with traces of blood…

“Oh, hell!” he spat out.

“Lincoln? What’s the matter?” Cooper glanced over at his boss, concerned.

Rhyme shouted, “Command, redial!”

The computer responded on the screen: I did not understand what you said. What would you like me to do?

“Redial the number.”

I did not understand what you said .

“Fuck it! Mel, Sachs… somebody hit redial!”

Cooper did and a few minutes later the criminalist was speaking once again to the warden in Amarillo.

“J. T., it’s Lincoln again.”

“Yes, sir?”

“Forget inmates. I want to know about guards .”

“Guards?”

“Somebody who used to be on your staff. With eye problems. Who whistled. And he might’ve worked on Death Row before or around the time Tucker was killed.”

“We all weren’t thinkin’ ’bout employees . And, again, most of our staff wasn’t here five, six years ago. But hold on here. Lemme ask around.”

The image of The Hanged Man had put the thought into Rhyme’s head. He then considered the weapons and the techniques that Unsub 109 had employed. They were methods of execution: cyanide gas, electricity, hanging, shooting a group of bullets into the heart, like a firing squad. And his weapon to subdue his victims was a baton, like a prison guard would carry.

A moment later he heard, “Hey there, Detective Rhyme?”

“Go ahead, J. T.”

“Sure ’nough, somebody said that rings a bell. I called one of our retired guards at home, worked execution detail. Name of Pepper. He’s agreed to come into the office and talk to you. Lives nearby. Should be here in just a few minutes. We’ll call you right back.”

Another glance at the tarot card.

A change of direction …

Ten insufferably long minutes later the phone rang.

Fast introductions were made. Retired Texas Department of Justice officer Halbert Pepper spoke in a drawl that made J. T. Beauchamp’s accent sound like the Queen’s English. “Thinkin’ I might be able to help y’all out some.”

“Tell me,” Rhyme said.

“Till ’bout five years ago we had us a executions control officer fit the bill of who y’all were describin’ to J. T. Had hisself eye trouble and he whistled up a storm. I was just ’bout to retire round then but I worked with him some.”

“Who was he?”

“Fella name of Thompson Boyd.”

Through the speakerphone, Pepper was explaining, “Boyd grew up round these parts. Father was a wildcatter -”

“Oil?”

“Field hand, yes, sir. Mother stayed at home. No other kids. Normal childhood, sounded like. Pretty nice, to hear tell. Always talkin’ ’bout his family, loved ’em. Did a lot for his mother, who lost a arm or leg or whatnot in a twister. Always looking out for her. Like one time, I heard, this kid on the street made fun of her, and Boyd followed him and threatened to slip a sidewinder into the boy’s bed some night if he didn’t apologize.

“Anyway after high school and a year’r two of college he went to work at his daddy’s company for a spell, till they had a string of layoffs. He got fired. His daddy too. Times was bad and he just couldn’t get work round here, and so he moved outa the state. Don’t know where. Got hisself a job at some prison. Started as a block guard. Then there was some problem – their executions officer went sick, I think – and there was nobody to do the job so Boyd done it. The burn went so good -”

“The what?”

“Sorry. The electrocution went so good they give him the job. He stayed for a while, but kept on movin’ from state to state, ’cause he was in demand. Became an expert at executions. He knew chairs -”

“Electric chairs?”

“Like our Ol’ Sparky down here, yes, sir. The famous one. And he knew gas too, was a expert at riggin’ the chamber. Could also tie a hangman’s noose and not many people in the U.S. ’re licensed for that line of work, lemme tell you. The ECO job opened up here and he jumped at it. We’d switched to lethal injections, like most other places, and he became a whiz at them too. Even read up on ’em so he could answer the protesters. There’s some people claim the chemicals’re painful. I myself think that’s the whale people and Democrats, who don’t bother to know the facts. It’s hogwash. I mean, we had these -”

“About Boyd?” asked impatient Lincoln Rhyme.

“Yes, sir, sorry. So he’s back here and things go fine for a spell. Nobody really paid him much mind. He was just kinda invisible. ‘Average Joe’ was his nickname. But somethin’ happened over time. Somethin’ changed. After a time he started to go strange.”

“How so?”

“The more executions he ran, the crazier he got. Kind of blanker and blanker. That make sense? Like he wasn’t quite all there. Give you a for-instance: Told you he and his folks was real tight, got along great. What happens but they get themselves killed in this car accident, his aunt too, and Boyd, he didn’t blink. Hell, he didn’t even go to the funeral. You would’ve thought he was in shock, but it wasn’t that way. He just didn’t seem to care. He went to his normal shift and, when ever’body heard, they asked what he was doin’ there. It was two days till the next execution. He coulda took time off. But he didn’t want to. He said he’d go out to their graves later. Don’t know if he ever did.

“See, it was like he kept gettin’ closer and closer to the prisoners – too close, a lot of folk thought. You don’t do that. Ain’t healthy. He stopped hangin’ out with other guards and spent his time with the condemned. He called ’em ‘my people.’ Word is that he one time even sat down in our old electric chair itself, which is in this sort of museum. Just to see what it was like. Fell asleep. Imagine that.

“Somebody asked Boyd about it, how’d it feel, bein’ in a electric chair. He said it didn’t feel like nothin’. It just felt ‘kinda numb.’ He said that a lot toward the end. He felt numb.”

“You said his parents were killed? Did he move into their house?”

“Think he did.”

“Is it still there?”

The Texans were on a speakerphone too and J. T. Beauchamp called out, “I’ll find that out, sir.” He posed a question to somebody. “Should see in a minute or two, Mr. Rhyme.”

“And could you find out about relatives in the area?”

“Yes, sir.”

Sachs asked, “You recall he whistled a lot, Officer Pepper?”

“Yes’m. And he was right good at it. Sometimes he’d give the condemned a song or two to send ’em off.”

“What about his eyes?”

“That too,” Pepper said. “Thompson had hisself bad eyes. The story is he was runnin’ a electrocution – wasn’t here – and somethin’ went bad. Happened sometimes, when you’d use the chair. A fire started -”

“The man being executed?” Sachs asked, wincing.

“That’s right, ma’am. Caught hisself on fire. He mighta been dead already, or unconscious. Nobody knows. He was still movin’ round but they always do that. So Thompson runs in with a riot gun, gonna shoot the poor fella, put him out of his misery. Now, that’s not part of protocol, I’ll tell you. It’s murder to kill the condemned before they die under the writ of execution. But Boyd was gonna do it anyway. Couldn’t let one of ‘his people’ die like that. But the fire spread. Insulation on the wire or some plastic or somethin’ caught and the fumes knocked Boyd out. He was blinded for a day or two.”

Читать дальше