The Detention Center was chaotic today. Shouts in the distance. A wailing voice or two.

“Me duele la garganta!”

“Yo, bitch-”

“Estoy enferma!”

“Yo, bitch, I’ma come over there and shut you up fo’ good.”

Five minutes later the green metal door opened, with a two-note creak. A guard came in, glanced at him. “You here for Washington? She’s not here.”

Pellam asked where she was.

“You better go to the second floor.”

“Is she all right?”

“Second floor.”

“You didn’t answer me.”

But the guard was gone.

He walked through the bleak corridors until he came to the dark alcove where he’d been directed. It was no less dirty but it was cooler and quieter. A guard glanced at his pass and let him through another door. He pushed inside and was surprised to see Ettie sitting at a table, hands clasped together. There was a bandage on her face.

“Ettie, what happened? Why’re you up here?”

“Isolation,” she whispered. “They were going to kill me.”

“Who?”

“Some girls. In the cell downstairs. They heard about the Torres boy dying. They fooled me pretty good. I thought they were my friends but they were planning all along to kill me. Louis got some court order or another to move me. The guards came just as those girls were about to burn me. They sprayed stuff on me and were gonna burn my face, John. The stuff, it hurt my skin.”

“How’re you feeling now?”

She didn’t answer. She said, “Oh, I never thought that boy’d die. That gave me a turn. Oh, the poor thing. He was such a sweet little one. If he’d been at his grandmother’s like he was supposed to be he’d still be live… I prayed for him. I did! And you know me – I don’t waste any time on religion.”

Pellam put his hand on Ettie’s good arm. He thought about saying, ‘He wasn’t in any pain,’ or ‘He went quickly,’ but of course he had no idea how much pain the boy had experienced or how quickly he’d died.

Finally she glanced at his unsmiling face. “I saw you in court. When you heard ’bout that time I got myself arrested… You want to know about that, I’ll bet.”

“What happened?”

“Remember the time Priscilla Cabot and me were working at that factory? The clothing place?”

“They fired you. A few years ago.”

“It was a desperate time for me, John. My sister’d been sick. And I didn’t have any money at all. I was beside myself. Anyway, this man Priscilla and I worked with, we all got laid off together and he had this idea to scare the company so they’d pay us money. We figured we were owed it, you know. Hell, I went along with ’em. Shouldn’t’ve. Didn’t really want to. But the long and short of it was they called up the owner and said his trucks were going to get wrecked if he didn’t pay us. We weren’t really going to do anything. At least, I wasn’t. And I didn’t know they threatened to burn them. I didn’t call; they did, Priscilla and this man.

“Anyway, the boss, he agreed but he called the police and we all got arrested and the other two said it was my idea. Well, the police didn’t believe I was the ringleader but I did get arrested and I spent some time in jail. I’m not proud of it. I’m pretty ashamed… I’m sorry, John. I didn’t tell you the truth ’bout that. I should’ve.”

“There’s no reason for you to tell me everything about yourself.”

“No, John. We were friends too. I shouldn’ta lied. Shoulda told Louis too. Didn’t help in court any.”

Near them someone laughed hysterically, the sound rising higher and higher until it became a faint scream. Then silence.

“You’ve got your secrets; I do too,” Pellam said. “I’ve kept some things from you.”

She looked at him closely. City life gives you a quick eye. “What is it, John?”

He was debating.

“Something you want to tell me, isn’t there?” she asked.

Finally he said, “Manslaughter.”

“What?”

“I did time for manslaughter.”

Her eyes grew still. It was a story that he had no interest to tell, no desire to relive. But he thought it was important to share it with her. And tell it he did – the story about the star of Pellam’s last feature film – the one never completed (the four canisters of film were sitting at the moment in his attic back in California). Central Standard Time . Tommy Bernstein, lovable, crazy, out of control. Only six setups left to shoot, four second-unit stunt gags. A week. Only a week. “ Just give me a little, John. Just to get me through wrap .”

But Pellam hadn’t given him a little. Pellam had given him lot and the man had stayed up in his cokeinduced frenzy for two days straight. Railing, laughing, drinking, puking. He died of a heart attack on the set. And the City of Angels’ District Attorney chose to go after Pellam in a big way for supplying the cocaine that caused it. He was the guilty party, the D.A. claimed, and the jury agreed, bestowing on Pellam conviction and some time in San Quentin.

“I am sorry, John.” She laughed. “Isn’t that a stitch? You, me and Billy Doyle. We’re all three of us jailbirds.” She squinted again. “You know who you remind me of? My son James.”

Pellam had seen pictures of the young man. Ettie’s oldest son, her only child by Doyle. Photographed in his early twenties, he was light-skinned – Doyle had been very pale – and handsome. Lean. James had dropped out of school several years ago and gone out west to make money. The last word from him was a card saying the young man was going to work in the “environmental field.”

That had been over a decade ago.

The guard glanced at her watch and Pellam whispered, “We don’t have much time. I’ve got to ask you a few questions. Now, that insurance policy they claim you bought had your checking account number on it and your signature on it. How’d somebody get them?”

“My checking account? Well, I don’t know. Nobody’s got my account number that I know ’bout.”

“Have you lost any checks lately?”

“No.”

“Who do you write checks to?”

“I don’t know… I pay my bills like everybody. Mama put that in me. Never let ’em get the edge on you, she always said. Pay on time. If you’ve got the money.”

“You written any checks to somebody you wouldn’t ordinarily?”

“No, not that I can think. Oh, wait. I had to pay some money to the government few months ago. They gave me too much social security by mistake. One check had three hundred more’n I ought to get. I knew about it but I kept it anyway. They found out and wanted it back. That’s what I hired Louis for. He handled it for me. All I had to pay was half what they wanted. I gave him check and he sent it to ’em with this form. See, the government, maybe they’re out to get me, John. Maybe the social security people and the police’re working together.”

This manic talk of conspiracies unsettled him. But Pellam cut her some slack. Under the circumstances she was entitled to be a little paranoid.

“How ’bout samples of your handwriting? How could somebody get them?”

“I don’t know.”

“Have you written any letters lately to somebody you don’t normally write?”

“Letters? I can’t think of any. I write to Elizabeth and send cards sometimes to my sister’s daughter in Fresno. Send ’em few dollars on their birthdays. That’s about it.”

“Anybody broken into your apartment?”

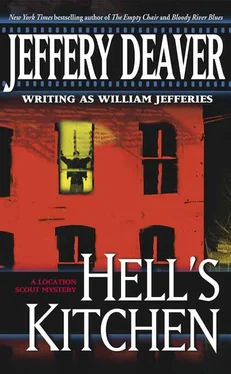

“No. I always lock my windows and door. I’m good about that. In the Kitchen you got to be careful. That’s the first thing you learn.” She played with her cast, traced Pellam’s signature. The answers made sense but they weren’t compelling. To a jury they might be true, might be fishy. As with so much else about Hell’s Kitchen he wasn’t sure what to believe.

Читать дальше