Insurance.

And fingerprints…

And damn if the color of the fire and the amount of smoke, all that technical stuff, hadn’t come right from his own mouth when he’d confronted Lomax at the scene, Pellam thought.

“The A.D.A.’s having a document examiner go over the insurance application to see if the handwriting matches hers. But there is a tentative match.” Bailey nodded his head in the direction Cleg, his green-jacketed emissary, had just disappeared. “I’m getting a copy of the report at the same time it’s sent to Ms. Koepel. If she hadn’t denied having the policy it probably wouldn’t have looked so bad for her.”

Pellam said, “Maybe she denied it because she didn’t take out the policy.” Bailey didn’t respond to that. Pellam returned to examining the report again. “The insurance is payable directly into her account. Is that unusual?”

“No, it’s pretty common. If a house or apartment burns, the company pays the proceeds directly into the bank. So the check wouldn’t be mailed to a place that no longer existed.”

“So whoever took out the policy would have to know her account number.”

“That’s right.” Bailey’s yellow pad was sun-faded around the edges. It looked like it was ten years old.

“Guns,” Pellam said, eyes on the report. “What do you think that means?

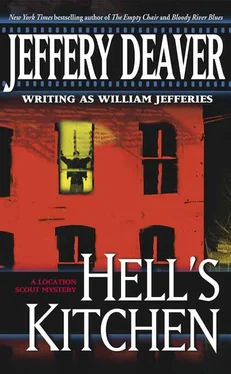

Bailey laughed. “That the apartment’s in Hell’s Kitchen. That’s all it means. There’re more guns here than on L.A. freeways.”

Which Pellam doubted very much. He asked, “Did you find out who the landlord is? And if the building was landmarked.”

“That’s why Cleg is delivering my thank-you presents.” Bailey rummaged in a file and dropped a photocopy on the desk. It bore the seal of the state attorney general. Bailey seemed to think this was a significant piece of paper but to Pellam it was legal gibberish. He shrugged, looked up.

The lawyer explained, “Yes, the building was landmarked but that’s irrelevant.”

“Why?”

“The owner’s a nonprofit foundation.” Bailey flipped through several pages and tapped an entry. Pellam read: The St. Augustus Foundation. 500 W. Thirty-ninth Street .

Everybody in the Kitchen knew about St. Augustus. It was a large church, rectory and Catholic school complex in the heart of the neighborhood and had been here forever. To the extent Hell’s Kitchen had a soul, St. Aug was it. In an interview Ettie had told him that Francis P. Duffy, the chaplain of the Kitchen’s famous World War I regiment, the Fighting 69th, had celebrated masses at St. Augustus before becoming pastor of Holy Cross Church.

Pellam asked skeptically, “You think they’re innocent just because it’s a church?”

“It’s the nonprofit part,” Bailey explained, “not the theological part. Any money that a not-for-profit makes has to stay in the organization. It can’t be distributed to its stockholders. Even when it’s dissolved. And the Attorney General and the IRS are always checking upon the books of nonprofits. Besides, the foundation had it insured for its book value – that was only a hundred thousand. Oh, sure, I’ve known a lot of priests who ought to go to jail for one thing or another but nobody’s going to risk sailing up to Sing Sing for that kind of small change.”

Pellam nodded at the papers. “Who’s this Father James Daly? He’s the director?”

“I called him an hour ago – he was out finding emergency housing for the tenants of the building. I’ll let you know when he calls back.”

Pellam then asked, “Can you get the name of the insurance agent Ettie talked to.”

“Sure, I can.”

Can. It was turning into the most expensive verb in the English language.

Pellam slid another two hundred, in stiff twenties, toward the lawyer. He sometimes thought ATMs should flash a message that read, “Are you going to spend this money wisely?”

He nodded out the window toward the high-rise. Bailey’s office was only two doors from Ettie’s burnt tenement and a haze of lingering smoke still obscured his view of the glitzy place. “Roger McKennah,” he said slowly. “Ettie said some of his workers from across the street were in the alley behind her building the night of the fire. Why’d they be there?”

But Bailey was nodding as if he wasn’t surprised at this news. “They’re doing some work here.”

“Here? In your building?”

“Right. He’s part-owner of this place. That’s the work going on outside. That you hear.” He nodded toward the sound of hammering in a hallway upstairs. “The new Donald Trump himself – renovating my building.”

“Why?”

“That’s a source of some speculation but we think, we think he’s fixing up a hideaway for his mistress on the second floor. But you know rumors. You don’t suspect him, do you?”

“Why shouldn’t I?”

Bailey glanced toward his wine bottle but forewent another glass. “I can’t believe he’d do anything illegal. Developers like McKennah steer clear of shenanigans. Why bother with small potatoes like burning an old tenement? He’s got hotels and offices all over the northeast. That new casino of his on the Boardwalk in Atlantic City just opened last month… You don’t look convinced.”

“A rule in Hollywood thriller scriptwriting is that if you don’t want to spend a lot of time developing your villain’s character just make him real estate developer or oil company executive.”

Bailey shook his head. “McKennah’s too top-drawer to do anything illegal.”

“Let me make a call.” Pellam took the phone.

The lawyer apparently changed his mind about the wine and graciously poured himself another. Pellam declined with a shake of his head as he punched in a long series of numbers. “Alan Lefkowitz, please.” After several clicks and long moments on hold, cheerful voice came on the phone.

“Pellam? The John Pellam? Shit. Where you be?”

Hating himself for it, Pellam slipped into producer-speak. “Big Apple. What’s cooking, Lefty?”

“Doing that thing with Polygram. You know. The Costner one. On the way to the set right now.”

Pellam couldn’t recall whether he owed multimillion-dollar producer Lefkowitz anything at the moment or whether Lefkowitz owed him . But Pellam took on a the creditor’s attitude one when he said, “I need some help here, Lefty.”

“You bet, Johnny. Talk to me.”

“You know all the big boys out here on the Right Coast.”

“Some.”

“Roger McKennah.”

“We rub elbows. He’s on the film board at Columbia. A trustee. Or NYU. I don’t remember.”

“I want to get in to see him. Or let’s say I want to look at him. Socially. His crib. Not the battlefields.”

Silence from the other coast. Then: “So… Why’d you be interested in that?”

“Research.”

“Ha. Research. Poking around. Gimme a minute.” Lefty remained on the line but grunted, somewhat breathlessly – as if he was making love though Pellam knew he was leaning across a massive desk and flipping through his address book. “Well, how’s this?”

“How’s what, Lefty?”

“You wanta go to a party. You live to party, right?”

The last party Pellam could recall attending had been two or three years ago. He said, “I’m party animal, Lefty.”

“McKennah pokes the social beast all the time. Drop my name and you’ll get in. I’ll make some calls. Find out where and when. I’ll call Spielberg.” (Spielberg’s assistant, he meant. And the call would finally end up with an assistant’s assistant located in an entirely different town than the chief raider of the lost ark was in.)

“My undying gratitude, Lefty. I mean it.”

Читать дальше