“After he was released I met him at his apartment, not far from here. It was a spring day in May, a beautiful day. Two in the afternoon. We were going to hire a boat. Right here, at this lake. I’d brought some stale bread to feed the birds. We were standing there and four Stormtroopers came up to us and pushed me to the ground. They’d followed us. They said they’d been watching him since he’d been released. They told him that the judge had acted illegally in releasing him and they were now going to carry out the sentence.” She choked for a moment. “They beat him to death right in front of me. Right there. I could hear his bones break. You see that-”

“Oh, Käthe. No…”

“ – you see that square of concrete? That was where he fell. That one. The fourth square from the grass. That was where Michael’s head lay as he died.”

He put his arm around her. She didn’t resist. But neither did she find any comfort in the contact; she was frozen.

“May is now the worst month,” she whispered. Then she looked around, at the textured canopy of summer trees. “This park is called the Tiergarten.”

“I know.”

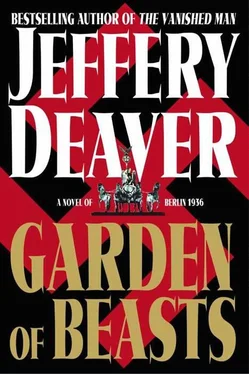

In English she said, “‘ Tier ’ means ‘animal’ or ‘beast.’ And ‘ Garten, ’ of course, is ‘garden.’ So, this is the garden of beasts, where the royal families of imperial Germany would hunt game. But in our slang ‘ Tier ’ also means thug, like a criminal. And that’s who killed my lover, criminals.” Her voice grew cold. “Here, right here in the garden of beasts.”

His grip tightened around her.

She glanced once more at the pond then at the square of concrete, the fourth from the grass. Käthe said, “Please take me home, Paul.”

In the hallway outside his door they paused.

Paul slipped his hand into his pocket and found the key. He looked down at her. Käthe in turn was staring at the floor.

“Good night,” he whispered.

“I’ve forgotten so much,” she said, looking up. “Walking through the city, seeing lovers in cafés, telling ribald jokes, sitting where famous writers and thinkers have sat… the pleasure in things like those. I’ve forgotten what that’s like. Forgotten so much…”

His hand went to the tiny scallop of cloth covering her shoulder, and then he touched her neck, felt her skin move against her bones. So thin, he thought. So thin.

With his other hand he brushed her hair out of her face. Then he kissed her.

She stiffened suddenly and he realized he’d made a mistake. She was vulnerable, she’d seen the site of her lover’s death, she’d walked through the garden of beasts. He started to back away but suddenly she flung her arms around him, kissing him hard, teeth met his lip and he tasted blood. “Oh,” she said, shocked. “I’m sorry.” But he laughed gently and then she did too. “I said I’ve forgotten much,” she whispered. “I’m afraid this is one more thing lost from my memory.”

He pulled her to him and they remained in the dim hallway, their lips and hands frantic. Images flashing past: a halo around her golden hair from the lamp behind her, the cream lace of her slip over the lighter lace of her brassiere, her hand finding the scar left by a bullet fired from Albert Reilly’s hidden Derringer, a.22 only but it tumbled when it hit bone and exited his biceps sideways, her keening moan, hot breath, the feel of silk, of cotton, his hand sliding down and finding her own fingers waiting to guide him through complicated layers of cloth and straps, her garter belt, which had been worn threadbare and stitched back together.

“My room,” he whispered. In a few seconds the door was open and they were staggering inside, where the air seemed hotter even than in the hot corridor.

The bed was miles away but the rose-colored couch with gull-wing arms was suddenly beneath them. He fell backward onto the cushions and heard a crack of wood. Käthe was on top of him, holding him in a vise grip by the arms as if, were she to let go, he might sink beneath the brown water of the Landwehr Canal.

A fierce kiss, then her face sought his neck. He heard her whisper to him, to herself, to no one, “How long has this been?” She began to unbutton his shirt frantically. “Ach, years and years.”

Well, he thought, not such a long time in his case. But as he lifted off her dress and slip in one smooth sweep, his hands sliding to the sweating small of her back, he realized that, while, yes, there’d been others recently, it had been years since he’d felt anything like this.

Then, gripping her face in his hands, bringing her closer, closer, losing himself entirely, he corrected himself once more.

Maybe it had been forever.

The evening rituals in the Kohl household had been completed. Dishes dried, linens put away, laundry done.

The inspector’s feet were feeling better and he poured out the water from the tub and then dried and replaced it. He tied the salts closed and put them back under the sink.

He returned to the den, where his pipe awaited. A moment later Heidi joined him and sat down in her own chair with her knitting. Kohl explained to her about his conversation with Günter.

She shook her head. “So that’s what it was. He was upset when he got home from the football field yesterday too. But he would say nothing to me. Not to a mother, not about such things.”

Kohl said, “We need to talk to them. Someone has to teach them what we learned. Right and wrong.”

Moral quicksand…

Heidi clicked the thick wooden needles together expertly; she was knitting a blanket for Charlotte and Heinrich’s first child, which she assumed would arrive approximately nine and a half months after their wedding next May. She asked in a harsh whisper, “And then what happens? In the school yard Günter mentions to his friends that his father says it’s wrong to burn books or that we should allow American newspapers in the country? Ach, then you’re taken away and never heard from again. Or they send me your ashes in a box with a swastika on it.”

“We tell them to keep what we say to themselves. Like playing a game. It must be secret.”

A smile from his wife. “They’re children, my darling. They can’t keep secrets.”

True, Kohl thought. How true. What brilliant criminals the Leader and his crowd are. They kidnap the nation by seizing our children. Hitler said his would be a thousand-year empire. This is how he will achieve it.

He said, “I will speak to-”

A huge pounding filled the hall – the bronze bear knocker on Kohl’s front door.

“God in heaven,” Heidi said, standing up, dropping the knitting and glancing toward the children’s rooms.

Willi Kohl suddenly realized that the SD or Gestapo had a listening device in his house and had heard the many questionable exchanges between himself and his wife. This was the Gestapo’s technique – to gather evidence on the sly then arrest you in your home either early in the morning or during the dinner hour or just after, when you would least expect them. “Quickly, put the radio on, see if there’s a broadcast,” he said. As if listening to Goebbels’s rantings would deter the political police.

She did. The dial glowed yellow but no sound yet came through the speakers. It took some moments for the tubes to heat up.

Another pounding.

Kohl thought of his pistol, but he kept it at the office; he never wanted the weapon near his children. Yet even if he had it, what good would it do against a company of Gestapo or SS? He walked into the living room and saw Charlotte and Heinrich, standing side by side, looking uneasily at each other. Hilde appeared in the doorway, her book drooping in her hand.

Читать дальше