I remembered writing that passage almost a year earlier and I also recalled having a distinct sense of satisfaction at my own abilities of expressing the complex mental and physical traits of a villain. I had thought, at the time, that I was conveying my own secret way of looking at a world that I knew was insincere and set on spoiling my own plans and ambitions.

But these words from the original Christmas tale—the so-called key to Obenreizer’s character—were flat, I realised now. Flat and silly and empty. And Fechter had used my words to endow his Obenreizer with a constantly skulking, furtive walk and look, combined with a manic stare—all too frequently aimed at nothing at all—that now impressed me as not the traits of a clever villain, but rather those of a village idiot after a serious concussion to his skull.

The audience loved it.

They also loved our new hero, George Vendale (who took the heroic palm from Walter Wilding when the latter died of his guiltless shame). Tonight I saw that George Vendale was a worse idiot than the skulking, smirking, brainlessly goggling Obenreizer. A child of three could have seen Obenreizer’s endless manipulations and falsehoods, yet Vendale—and several hundred people in that night’s audience—accepted our silly premise that the hero was simply a sweet, trusting soul.

If our race had produced only a few sweet, trusting souls like George Vendale, the species would have died out from sheer stupidity millennia ago.

Even the setting in the Swiss Alps, I realised while watching with the scarab’s clarity, was silly and unnecessary. The action leaping back and forth from London to Switzerland had no purpose except to bring in some of the spectacle that Dickens and I had seen in our journey across the Alps in 1853. The last scenes in the play, where Vendale’s beloved, Margaret Obenreizer (the villain’s beautiful and sinless niece), revealed that Vendale had not died from being hurled down the glacier a year earlier, but had been in her secret care all that time in a cosy little Swiss chalet presumably at the base of the aforementioned glacier, came close to making me bark with derisive laughter.

The scene where Obenreizer the Clever (who had lured Vendale all that way to that very ice-bridge above the abyss a year before) set forth across the treacherous slope for no other reason than the play’s ending demanded a sacrifice of him, not only stretched my newly awakened scepticism to the breaking point, but snapped it entirely. I wished to God that Fechter had been flinging himself into an actual bottomless abyss that night rather than merely dropping eight feet to a pile of mattresses hidden from the audience’s view behind a painted wooden spire of ice.

I had to close both eyes in the final scene where Obenreizer’s body was being borne into the little Swiss village celebrating Vendale’s and Margaret’s marriage (why wouldn’t they have married in London, for God’s sake?), with the happy couple exiting in exultance on stage right and with Obenreizer’s lifeless body being carried in a litter off stage left as the audience simultaneously hissed at the villain’s funeral and wept and cheered the wedding. The juxtaposition, seemingly so clever when Dickens and I outlined it on the page, was puerile and absurd in the clarity of my scarab-vision. But the audience hissed and cheered on as Fechter’s body was carried off stage left and our newly married couple rolled away in their marriage coach stage right.

The audience were idiots. The play was being performed by idiots. Its script was sheer melodrama idiocy penned by an idiot.

In the lobby after the play— and after five hundred people had pressed close to shake Dickens’s hand or tell him how wonderful his play had been (I was all but forgotten, it seemed, as the true playwright, which—on this night of revelation—I did not mind a bit)—Dickens said to me, “Well, my dear Wilkie, the play is a triumph. There is no doubt of it. But, to use your Moonstone language, it remains a diamond in the rough. There are excellent things in it… excellent things!.. but it still drags a tad.”

I stared at him. Had Dickens just seen the same play I had?

“There are too many pieces of stagecraft missed as it is now being produced,” continued Dickens. “Too many opportunities to heighten both the drama and Obenreizer’s villainy have been missed in this version.”

I had to use all my strength not to laugh in the Inimitable’s face. More stagecraft, more drama, and more villainy were the last things on earth this giant, steaming pile of overacted, melodramatic heap of horse apples needed. What it needed, I thought, was a shovel and a deep hole in a distant place in which to bury it.

“You know, of course, that while Fechter soon may have to leave this performance for reasons of health,” continued Dickens, “we fully intend to put on a new version of No Thoroughfare at the Café Vaudeville in Paris early next month with, one hopes, Fechter, sooner or later, reprising his success as Obenreizer.”

Reprising this public pratfall onto our collective arse was my only thought.

“I shall personally oversee the revisions and perhaps act as stage manager at Vaudeville Théâtre until the play is on its feet,” said Dickens. “I do hope you shall be coming along with us, Wilkie. It should be great fun.”

“I am afraid that will not be possible, Charles,” I said. “My health simply will not permit it.”

“Ahh,” said Dickens. “I am heartily sorry for that.” I could detect no actual regret in his voice and almost certainly could hear an undertone of relief. “Well,” he said, “Fechter will be too exhausted to go out with us afterwards, so I shall drop in on him backstage and convey our congratulations at the excellence of what may be his last performance as Obenreizer… in this version of the play at least!”

And with that, Dickens bustled away, still being congratulated by the last of the passing theatre-goers.

Beard, who was going out with us later, was chatting with others so I stepped out into the street. The air smelled of horse manure, as the air outside all theatres did after the carriages and cabs had taken away the well-dressed members of the night’s audience. The stink seemed appropriate.

As it turned out, Dickens kept Beard and me waiting for more than half an hour. I later learned that he had loaned the weeping Fechter £2,000… a fact that was especially galling, since I had loaned the foolish actor £1,000 that I could scarce afford only two weeks earlier.

While I waited alone in the barnyard miasma, I drank deeply from my silver flask of laudanum and realised that for all of Dickens’s talk of theatrical triumph in France, he would not be staying there past the first week of June.

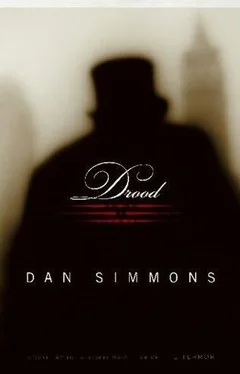

Drood and the scarab would bring him back to London on or before 9 June. It would be the third anniversary of the Staplehurst accident. Charles Dickens had a date for that night, I was certain, and this year I vowed that I would spend it with him.

I swallowed the last of the laudanum and smiled a smile much colder and more villainous than anything Fechter as Obenreizer could ever have managed.

By the end of May, I had learned (through Mrs G—, Caroline’s elderly mother-in-law, who now came to stay with us from time to time at Number 90 Gloucester Place, since it would have been inappropriate for Carrie to live in a bachelor’s home without at least an occasional chaperone for respectability’s sake) that Caroline was now living with Joseph Charles Clow’s mother, the widow of the distiller. They had set a wedding date for early October. The news did not discomfit me in the least; on the contrary, it seemed the proper step at the proper time for the proper people. And speaking of propriety, after I received a somewhat panicked letter from Caroline herself, I wrote to assure her that I would help her create and maintain to the death any fiction of her past or her family (much less of my own relationship with her) that she chose to present to the low-bourgeois and somewhat puritanical Clow clan.

Читать дальше