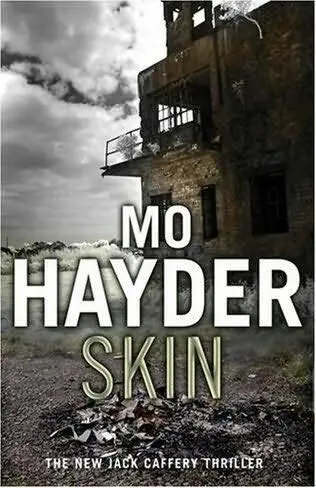

The fourth book in the Jack Caffery series, 2009

I couldn’t, and wouldn’t, have even attempted to start this book if it hadn’t been for one man: Sergeant Bob Randall of the Avon and Somerset Underwater Search Unit. He knows his contribution, he knows how I value it, but there is no harm in the world hearing what a unique, informed and brilliant police officer he is, nor how generous and tireless he has been in helping me, both professionally and personally. I had other help, too, in inching the police procedural details a little closer to reality: DI Steven Lawrence of the CID training unit and Alan Andrews of the Major Crime Review Team, both of Avon and Somerset Constabulary. And, from the Metropolitan Police, Cliff Davies of the Homicide Review Team, who is still after all these years an inspiration and a friend.

It’s a rare person who can call many of her colleagues friends, so I am lucky beyond words to both know and work with three extraordinary women: Jane Gregory, Selina Walker and Alison Barrow. Nor could I keep going without the unswerving support of Jemma McDonagh; Claire Morris; Terry Bland; Stephanie Glencross and Tess Barun at Gregory and Company, not to mention everyone at Transworld Publishers whom I’m honoured to still be working with ten years down the line: Larry Finlay; Ed Christie; Janine Giovanni; Diana Jones; Nick Robinson; the indomitable eco-man Bradley Rose; Simon Taylor; Claire Ward; Hazel Orme; Katrina Whone and Joanne Williamson.

My friends and family who listen and inspire in equal measure are: Christian Allis, John and Aida Bastin; the Billinghams; Kate Butler; Linda, Liz and Laura Downing; the Fiddlers; the Gores; the Heads; Mairi, Moë and Sally Hitomi; Sue and Don Hollins; Patrick and ALF Janson-Smith; Karen Knowlton; the Macers; Rebecca Marshall; Margaret and E. A. Murphy; Selina Perry; Helen Piper; Keith Quinn; Karin Slaughter; Sophie and Vincent Thiebault; Ness Williams; and the ever graceful Gilly Vaulkhard.

And, of course, a big, big thank you to three lovely little girls; first Misty and Daisy, who selflessly lent me their names without holding any conditions about what happened to their fictional counterparts, second, and most of all, a little girl who has surprised me by being the greatest, and most unexpected, love of all: my beautiful daughter, Lotte Genevieve Quinn.

Human skin is an organ. The biggest organ in the body, it comprises the dermis, the epidermis and a subcutaneous fatty layer. If it were to be removed intact and spread out it would cover an area just under two square metres. It has weight too: with all that protein and adherent fat, it has enormous bulk. The skin of a healthy adult male would weigh ten to fifteen kilos, depending on his size. The same as a large toddler.

The skin of a woman, on the other hand, would weigh marginally less. It would cover a smaller area too.

Most middle-aged men, even the ones who live alone in a remote part of Somerset, wouldn’t have given any thought to what a woman would look like without her skin. Neither would they have cause to wonder what her skin would look like stretched and pinned out on a workbench.

But, then, most men are not like this man.

This man is a different sort of person altogether.

Deep in the rain-soaked Mendip Hills of Somerset lie eight flooded limestone quarries. Long disused, they have been numbered by the owners from one to eight, and are arranged in a horseshoe shape. Number eight, at the most south-easterly point, nearly touches the end of what is called locally the Elf’s Grotto system, a network of dripping caves and passages that reach deep into the ground. Local folklore has it there are secret exits from this cave system leading into the old Roman lead mines, that in ancient times the elves of Elf’s Grotto used the tunnels as escape routes. Some say that because of all the twentieth-century blasting, these tunnels now open directly into the flooded quarries.

Sergeant ‘Flea’ Marley, the head of Avon and Somerset ’s underwater search unit, slid into quarry number eight at just after four on a clear May afternoon. She wasn’t thinking about secret entrances. She wasn’t looking for holes in the wall. She was thinking about a woman who’d been missing for three days. The woman’s name was Lucy Mahoney, and the professionals on the surface believed her corpse might be down here, somewhere in this vast expanse of water, curled in the weeds on one of these ledges.

Flea descended to ten metres, wiggling her jaw from side to side to equalize the pressure in her ears. At this depth the water was an eerie, almost petrol blue – just the faintest milky limestone dust hanging where her fins had stirred it up. Perfect. Usually the water she dived was ‘nil vis’ – like swimming through soup, everything having to be done by touch alone – but down here she could see at least three metres ahead. She moved away from her entry point, handholding herself along the quarry wall until the pressure on her lifeline was constant. She could see every detail, every wafting plant, every quarried boulder on the floor. Every place a body might have come to rest.

‘Sarge?’ PC Wellard, her surface attendant, spoke into the comms mike. His voice came into her ear as if he was standing right next to her. ‘See anything?’

‘Yes,’ she murmured. ‘Into the future.’

‘Eh?’

‘I can see into the future, Wellard. I see me coming out of here in an hour freezing cold. I see disappointment on everyone’s face that I’m empty-handed.’

‘How come?’

‘Dunno. Just don’t think she’s down here. It feels wrong. How long’s she been missing?’

‘Two and a half days.’

‘And her car. Where was it parked?’

‘Half a mile away. On the B3135.’

‘They thought she was depressed?’

‘Her ex was interviewed for the misper report. He’s adamant she wasn’t.’

‘And there’s nothing else linking her to the quarry? No belongings? She’d not been here before or anything?’

‘No.’

Flea finned on, the umbilical lead – the air and communication line that linked her to the surface – trailing gently behind. Quarry number eight was a notorious suicide spot. Maybe the police search adviser, Stuart Pearce, disagreed with the family about Lucy Mahoney’s state of mind. Maybe that was why he’d put this particular pin in the map and detailed them to do this search. Either that or he was grasping at straws. She’d encountered Stuart Pearce before. She thought it was the latter.

‘Could she swim, Wellard? I forgot to ask.’

‘Yeah. She was a good swimmer.’

‘Then if she’s a suicide she’ll have weighted herself down. A rucksack or something. Which means she’ll be near the edge. Let’s run this pendulum search pattern out to ten metres. No way she’ll be further out than that. Then we’ll switch to the other side of the quarry.’

‘Uh, Sarge, there’s a problem with that. You do that pattern and it’ll take you to deeper than fifty metres.’

Wellard had the quarry schematic. Flea had already studied it surfaceside. When the quarry company had made finger-shaped holes to pack explosives they’d used ten-metre-long drills, which meant that the quarry, before they’d turned off the pumps and allowed it to flood, had been blasted away in ten-metre slices. At one end it was between twenty and thirty metres. At the other end it was deeper. It dropped to more than fifty metres. The Health and Safety Executive’s rules were clear: no police diver was cleared to dive deeper than fifty. Ever.

Читать дальше