“Why are you so hard on yourself?” She took his hand across the table. “You are doing your best in a difficult situation. I understand.”

But there was a lot she might not understand. He did not make an immediate response.

She continued, “Did you tell Party Secretary Li about the parking lot deal with Gu?”

“No, I didn’t.” He had anticipated this question. Li had shown no surprise at his dealing with Gu. It appeared as if Li had known about it.

How deeply was Li connected with the Blue? As the number-one police official responsible for the security of the city, Party Secretary Li might have had to maintain some sort of working relationship with the local triad. In the Party’s newspapers, the slogan, “political stability,” was still emphasized as the highest priority after the eventful summer of 1989. But he seemed to be more deeply involved.

“What about Qian’s light green cell phone?” she said. “I did not remember seeing one in the market.”

“When you were behind the fitting room curtain, I saw someone dialing a cell phone of the same unusual color.”

A melody was being played in the bar. It was another song that had been popular during the Cultural Revolution. Chen failed to remember its words except for one refrain- ”We shall be beholden to Chairman Mao, generation after generation.” He shook his head.

“What is it?”

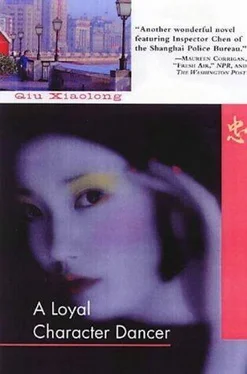

“Just the song.” He was relieved at the change of topic. “There is a revival of those popular songs from the time of the Cultural Revolution. This one’s a Red Guard song. Wen could have danced the loyal character dance to it.”

“Do people miss those songs?”

“They appeal to people, I think, not because of their contents, but they were part of people’s lives-for ten years.”

“Which holds meaning for them, the melody or their memories?” she said, subtly echoing the line he had recited for her in the Suzhou garden.

“I don’t have the answer,” he said, thinking of another question that had just come up in their conversation.

Was he himself a loyal character dancer, in a different time and place?

He’d better turn in a report to Minister Huang now. He was not yet sure what exactly to say. At this stage of his career, it might be best for him to show his loyalty directly to the Beijing ministry, circumventing Party Secretary Li.

“What are you thinking about, Chief Inspector Chen?”

“Nothing.”

They heard Party Secretary Li calling to them from a distance, “Comrade Chief Inspector Chen, boarding in ten minutes.”

Li was walking toward the cafe, pointing at the new information displayed on the screen above the gate.

“I’m coming,” he responded before he turned back to her. “I have something for you too, Inspector Rohn. When Liu did his shopping for Wen on the way to the airport, I chose a fan and copied several lines on it.”

Long, long I lament

there is not a self for me to claim,

oh, when can I forget

all the cares of the world?

The night deep, the wind still, no ripples on the river.

“Your lines?”

“No, Su Dongpu’s.”

“Can you recite the poem for me?”

“No, I cannot remember the rest of the poem. These few lines alone came to me.”

“I’ll find the poem in a library. Thank you, Chief Inspector Chen.” She stood up, folding the fan.

“Hurry up. Please. It’s time,” Party Secretary Li urged.

The line of passengers started moving through the gate.

“Hurry up.” Qian was now at Li’s side, holding that light green cell phone in his hand.

Wen and Liu stood at the end of the newly formed line, holding each other’s hand.

It would be Chief Inspector Chen’s responsibility to separate the two, and to send Wen through the gate.

And Inspector Rohn, too.

Along with a part of himself, he thought, though he might have lost it long ago, perhaps as early as those mornings on the dew-decked green bench in Bund Park.

***