“Unless you speak Finnish, you wouldn’t understand.”

“Read some anyway.”

“I doubt you will find this on your list of texts approved by the Communist Party.”

“If you won’t tell, then I promise that neither will I.”

Pekkala shrugged. “Very well.” He opened the book and began to read, the Finnish words rolling like thunder in his throat and cracking off the roof of his mouth like the snap of lightning in the air. Although he read from this book all the time, he rarely spoke its text out loud, and it had been years since he’d had the chance to speak his native tongue. Even his brother had abandoned it. As he read now, it sounded both distant and familiar, like a memory borrowed from another person’s life.

After a minute, he stopped and looked up at Kirov.

“Your language,” Kirov said, “sounds like someone prying nails out of wood.”

“I’ll try to find some way to take that as a compliment.”

“What did it mean?”

Pekkala’s gaze returned to the book. He stared at the words and slowly they began to change, speaking to him in the language Kirov could understand. He told Kirov the story of the wanderer Väinämöinen and his attempts to persuade the goddess Pohjola to come down from the rainbow where she lived and join him in his travels. Before she would agree, Pohjola gave Väinämöinen impossible tasks to perform, such as tying an egg into a knot, splitting a horsehair with a dull knife, and scraping birch bark from a stone. While performing the final task, which was to make a ship out of wood shavings, Väinämöinen gashed his knee with an axe. The only thing which would stop the bleeding was a spell called the Source of Iron, and Väinämöinen set out to find someone who knew the magic words.

“Are they all as strange as that?”

“They are strange until you understand them,” replied Pekkala, “and then it is as if you’ve known them all your life.”

“Did you ever read that story to Alexei?” asked Kirov.

“I read him some, but not that one. To hear of a spell like that would have given him hope where there was none.” As he spoke these words, Pekkala could not help wondering if his own hopes for finding Alexei alive were as hollow as a spell to stop the boy’s bleeding.

EARLY THE NEXT MORNING, SOMEONE KNOCKED ON THE FRONT DOOR. “Mayakovsky!” groaned Kirov, rubbing the sleep out of his eyes. “I hope he’s brought more than potatoes.”

“That’s not Mayakovsky,” Pekkala said. “He always comes through the courtyard.” He got up and stepped over Anton, who had returned sometime that night.

Opening the door, he found Kropotkin waiting on the other side. The police chief wore his blue service tunic, but had left all the buttons undone. His uniform cap was nowhere in sight and his hands remained tucked in his pockets. His straight combed hair and squared-off jaw gave him the appearance of a boxer dog.

Kropotkin was the most slovenly-looking policeman Pekkala had ever seen. The Tsar would have fired him on the spot, thought Pekkala, for daring to appear like that.

“A call came in for you last night,” said Kropotkin.

“Who from?”

“The asylum at Vodovenko. Katamidze says he has remembered something you asked him about. A name.”

Pekkala’s heart slammed in his chest. “I will leave immediately.”

“I already told your Cheka man,” he said. “I met him at the tavern last night. I gave him the message, but I thought he might be too drunk to understand me. I thought I’d better come by this morning, just to be sure you got the news.”

“I’m glad you did,” said Pekkala.

Kropotkin rattled the change in his pockets. “Look, Pekkala, I know we didn’t get off to a good start, but if there is anything I can do to help you, you know where to find me.”

Pekkala thanked him and closed the door.

Anton was still asleep, wrapped in a blanket.

Pekkala took one corner of the blanket and heaved it upwards.

Anton rolled out onto the floor cursing. “What’s going on?”

“Katamidze! The telephone call from Vodovenko! Why didn’t you tell us last night?”

Anton struggled upright, bleary-eyed. “I was going to tell you in the morning.” Just above the velvet curtains, bolts of sunlight slanted through the windows, illuminating dust which spiraled slowly through the air. “But I guess it is the morning, so I’m telling you now.”

“We should have been on the road hours ago.” Pekkala grabbed Anton’s clothes off the floor and threw them in his face. “Get dressed. We’re leaving now.”

Kirov appeared out of the kitchen. “Fried army meat for breakfast!” he announced.

Pekkala pushed past him and out into the courtyard.

Kirov watched him go, the smile fading from his face. “What’s going on?” Then he turned to Anton and asked again, “What’s the matter?”

Anton was pulling on his boots. “Get in the car,” he said.

Ten minutes later, they were on the road.

Driving south to Vodovenko, they passed through the village of the temporary lie. The barrier was down over the road but they found the guardhouse locked and unmanned.

After moving the barricade, they continued on and soon found themselves on the main street. The place was deserted, as if the population had abruptly fled, leaving behind shops whose windows brimmed with bread, meat, and fruit. But when Pekkala got out of the car to have a closer look, he realized that everything behind the glass was made of wax.

They stopped at the little railway station and looked off down the empty tracks, which trailed out to the horizon. A broom stood propped against one of the support columns of the station house roof.

None of them spoke. The emptiness of the place seemed to command their silence.

Pekkala thought back to the faces he had seen when they passed through before. He remembered the fear hidden behind the masks of their smiles.

They got in the car and drove on.

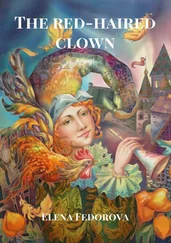

Later that day, when they pulled into the courtyard at Vodovenko, the red-haired attendant came out to meet them.

“You’re too late,” he said.

Pekkala climbed out of the car, his hip joints sore from sitting cramped inside the Emka. “What do you mean we are late?”

“Not late.” The attendant shook his head. “Too late.”

“What happened?”

“We’re not sure. A suicide, we think.”

The three men did not bother to sign in and the attendant did not ask for their weapons. They hurried through the armored door and down the corridors until they came to a room whose floor and walls up to chest height were plated with white tiles, like those inside a shower. Four large lights hung down from the ceiling. It was the mortuary.

Katamidze’s body lay on a metal-topped table, half covered with a cotton blanket. The photographer’s lips and eyelids and the tip of his nose had turned a mottled blue, but the rest of his skin looked as pale as the tiles on the walls. His feet, which were facing the door, stuck out from under the blanket. Attached by wire to the big toe of his right foot was a metal disk on which a number had been stamped. The nails had turned a yellow color, like the scales of a dead fish.

Anton leaned against the wall by the door, his eyes fixed on the floor.

Kirov followed behind Pekkala, too curious to be appalled.

“Poison,” said Pekkala.

“Yes,” agreed the attendant.

“Cyanide?”

“Lye,” said the attendant.

Gently, Pekkala set his hand on Katamidze’s face and lifted one of the eyelids. The whites of the dead man’s eyes had turned red from burst blood vessels. Examining the area around the eyes, Pekkala noticed a faint blush extending from the cheekbone up to the line of the forehead. He traced his fingers down the side of the man’s neck, probing the flesh. When he reached Katamidze’s larynx he traced his finger over fragile horseshoe-shaped bone. It gave under gentle pressure, indicating that it had been crushed. “Whoever killed him,” he said, “held on to his throat until he was sure Katamidze would not survive, but it was not strangulation that killed him. Where was he found?”

Читать дальше