Like most men, Gabriel had heard the myth that one’s life flashed before one’s eyes in the moments before death. In reality, as he had felt the cold rasp of death’s scythe cutting through the air close by his face, its chill in stark contrast to the burning that had followed the impact of the bullets, he had experienced no such visions. Now, as he pieced together what had occurred, he recalled only a vague sense of surprise, as though he had bumped into a stranger on a street and, looking into his face to apologize, had recognized an old acquaintance, his arrival long anticipated.

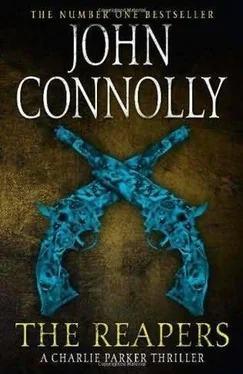

No, the events of his life had come to him only later as he lay in a drug-induced stupor on the hospital bed, the narcotics causing the real and the imagined to mingle and interweave, so that he saw his now-departed wife surrounded by the children they had never had, an imaginary existence the absence of which brought no sense of regret. He saw young men and women dispatched to end the lives of others, but in his dreams only the dead returned, and they spoke no words of blame, for he felt no guilt at what he had done. For the most part, he had rescued them from lives that might otherwise have finished in prisons or poor men’s bars. Some of them had come to violent ends through Gabriel’s intervention, but that ending had been written for them long before they met him. He had merely altered the place of their termination, and the duration and fulfillment of the life that preceded it. They were his Reapers, his laborers in the field, and he had equipped them to the best of his abilities for the tasks that lay before them.

Only one walked in Gabriel’s dreams as he did in life, and that was Louis. Gabriel had never quite understood the depth of his affection for this troubled man. His dream gave him an answer of sorts.

It was, he thought, because Louis had once been so like himself.

Gabriel heard a chair shift in the corner of the room. He opened his eyes a little wider. Carefully, he turned his head in the direction of the sound, and was pleased to find that he had more movement than before, even if the discomfort that it caused was still great. There was a shape against the window, a disturbance in the symmetry of the horizontal bars of the half-closed blinds. The shape grew larger as the man rose from his chair and approached the bed, and Gabriel recognized him as he drew closer.

“You’re a difficult man to kill,” said Milton.

Gabriel tried to speak, but his mouth and throat were still too dry. He gestured at the jug of water by his bedside, and winced at the pain the movement brought. It was that damned needle in the back of his hand. He could feel it in the vein. Gabriel had been hospitalized twice in the previous ten years: once for the removal of a benign tumor, the second time for a hairline fracture of his right femur, and on both occasions he had been strangely resentful of the connector in his hand. Odd, he thought: the injuries that have brought me to this place are more serious and painful than a thin strip of metal inserted into a blood vessel, and yet it is this upon which I choose to focus. It is because it is small, a nuisance rather than a trauma. It is understandable. Its purpose is known to me. And today, at this moment, it represents the first step in coming to terms with what has happened.

Milton poured a glass of water for him, then held it to Gabriel’s mouth so that he could sip from it, supporting the old man’s head gently with his right hand as he did so. It was a curiously intimate, tender gesture, yet Gabriel was resentful of it. Before, they had been equals, but they would never be so again, not after Milton had seen him reduced to this, not after he had touched his head in that way. Even though there was kindness in the action, Milton could not have been unaware of what it meant to Gabriel and his dignity, his sense of his own place in the complex universe that he inhabited. A little of the liquid dribbled down Gabriel’s chin, and Milton wiped it for him with a tissue, compounding Gabriel’s anger and embarrassment, but he did not show his true feelings, for that would be to surrender entirely to them and humiliate himself still further. Instead, he croaked a thank you and let his head sink back onto the pillows.

“What happened to me?” he asked, the words little more than a whisper.

“You were shot. Three bullets. One missed your heart by about an inch, another nicked your right lung. The third shattered your collarbone. I believe the appropriate thing to say in these situations is that you’re lucky to be alive. Not for the first time, I might add.”

He lowered his head slightly, as though to hide the expression upon his face, but Gabriel’s eyes had briefly closed and he missed the gesture.

“How long?” asked Gabriel.

“Two days, or a little more. They seem to think you’re some kind of medical marvel; that, or God was watching over you.”

The ghost of a smile formed on Gabriel’s lips. “Except God does not believe in men like us,” he said, and was pleased to see a frown appear on Milton’s face. “Why”-he paused to draw a breath-“are you here?”

“Can’t one old friend visit another?”

“We’re not friends.”

“We are as close to friends as either of us have,” said Milton, and Gabriel inclined his head slightly in reluctant agreement. “I’ve been watching over you,” continued Milton. He gestured toward the camera in the corner.

“You’re a little late.”

“We were concerned that someone might try to finish the job.”

“I don’t believe you.”

“It doesn’t matter what you believe.”

“And are you my only visitor?”

“No. There was another.”

“Who?”

“Your favorite.”

Gabriel smiled again.

“He believes this was linked to the earlier attacks,” said Milton. “He’s going after Leehagen.”

The smile faded as Gabriel regarded Milton carefully.

“Why should Leehagen interest you?”

“I never claimed that he did,” said Milton, as he waited to be questioned further. He thought that he saw something flit across Gabriel’s features, a vague awareness of hidden knowledge. Milton leaned in closer to him. “But I have some information for you. You asked me to find out what I could about Leehagen and Hoyle; most of it I suspect you already know. There was an anomaly, though, for want of a better word.”

Gabriel waited.

“The one who called himself Kandic wasn’t hired to kill Leehagen.”

Gabriel considered what he had been told. His mental functions were still impaired by the drugs, and his mind was clouded. He tried desperately to clear it, but the narcotic fug was too strong. Under other circumstances, he would have made the deductions required alone, but now he needed Milton to lead him. He swallowed, then spoke.

“Who was he sent to kill?”

“My source says Nicholas Hoyle.”

“By Leehagen?”

Milton shook his head. “Someone further afield. Hoyle is involved in an oil deal in the Caspian. It appears that there are some who would prefer it if he was involved no longer. My source also says that whatever occurred between Hoyle and Leehagen in the past, it has now been forgotten, if the feud ever truly existed in the form that was claimed. It seems they have used the rumor of their mutual antagonism to their shared advantage. ‘My enemy’s enemy is my friend’: at times, Hoyle’s rivals have approached Leehagen, and Leehagen’s enemies have approached Hoyle. Each man used the approaches to learn what he could to the other’s advantage. It’s an old game, and one that they’ve played well. They also share an interest in young women-very young women-or they did until Leehagen’s illness began to take its toll. Leehagen still supplies Hoyle’s needs. The girls have to be untouched. Virgins. Hoyle has a phobia about disease.”

Читать дальше