Christopher A. Bohjalian

The Double Bind

For Rose Mary Muench

and

in memory of Frederick Muench (1929-2004)

“Oh, I know who Pauline Kael is,” he said. “I wasn’t born homeless, you know.”

– NICK HORNBY, A Long Way Down

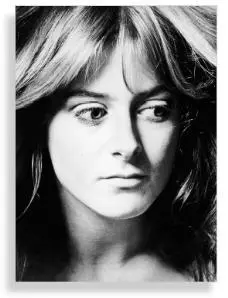

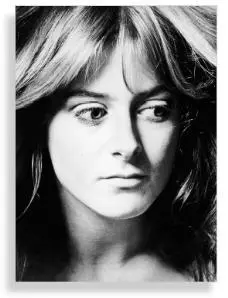

THIS NOVEL HAD ITS ORIGINS IN DECEMBER 2003, when Rita Markley, the executive director of Burlington, Vermont ’s, Committee on Temporary Shelter, shared with me the contents of a box of old photographs. The black-and-white images had been taken by a once-homeless man who had died in the studio apartment her organization had found for him. His name was Bob “Soupy” Campbell.

The photos were remarkable, both because of the man’s evident talent and because of the subject matter. I recognized the performers-musicians, comedians, actors-and newsmakers in many of them. Most of the photos were at least forty years old. We were all mystified as to how Campbell had gone from photographing luminaries from the 1950s and 1960s to winding up at a homeless shelter in northern Vermont. He had no surviving family we were aware of that we could ask.

The reality, of course, is that Campbell probably wound up homeless for any one of the myriad reasons that most transients wind up on the streets: Mental illness. Substance abuse. Bad luck.

We tend to stigmatize the homeless and blame them for their plight. We are oblivious to the fact that most had lives as serious as our own before everything fell apart. The photographs in this book are a testimony to that reality: They were taken by Campbell before he wound up a transient in Vermont.

Consequently, I am grateful to Burlington ’s Committee on Temporary Shelter for allowing me to use these photographs in this story. Obviously, Bobbie Crocker, the homeless photographer in this novel, is fictitious. But the photographs you will see in this book are real.

L AUREL ESTABROOK was nearly raped the fall of her sophomore year of college. Quite likely she was nearly murdered that autumn. This was no date-rape disaster with a handsome, entitled UVM frat boy after the two of them had spent too much time flirting beside the bulbous steel of a beer keg; this was one of those violent, sinister attacks involving masked men-yes, men, plural, and they actually were wearing wool ski masks that shielded all but their eyes and the snarling rifts of their mouths-that one presumes only happens to other women in distant states. To victims whose faces appear on the morning news programs, and whose devastated, forever-wrecked mothers are interviewed by strikingly beautiful anchorwomen.

She was biking on a wooded dirt road twenty miles northeast of the college in a town with a name that was both ominous and oxymoronic: Underhill. In all fairness, the girl did not find the name Underhill menacing before she was assaulted. But she also did not return there for any reason in the years after the attack. It was somewhere around six-thirty on a Sunday evening, and this was the third Sunday in a row that she had packed her well-traveled mountain bike into the back of her roommate Talia’s station wagon and driven to Underhill to ride for miles and miles along the logging roads that snaked through the nearby forest. At the time, it struck her as beautiful country: a fairy-tale wood more Lewis than Grimm, the maples not yet the color of claret. It was all new growth, a third-generation tangle of maple and oak and ash, the remnants of stone walls still visible in the understory not far from the paths. It was nothing like the Long Island suburbs where she had grown up, a world of expensive homes with manicured lawns only blocks from a long neon-lit swath of fast-food restaurants, foreign car dealers, and weight-loss clinics in strip malls.

After the attack, of course, her memories of that patch of Vermont woods were transformed, just as the name of the nearby town gained a different, darker resonance. Later, when she recalled those roads and hills-some seeming too steep to bike, but bike them she did-she would think instead of the washboard ruts that had jangled her body and her overriding sense that the great canopy of leaves from the trees shielded too much of the view and made the woods too thick to be pretty. Sometimes, even many years later, when she would be trying to fight her way to sleep through the flurries of wakefulness, she would see those woods after the leaves had fallen, and visualize only the long finger grips of the skeletal birches.

By six-thirty that evening the sun had just about set and the air was growing moist and chilly. But she wasn’t worried about the dark because she had parked her friend’s wagon in a gravel pull-off beside a paved road that was no more than three miles distant. There was a house beside the pull-off with a single window above an attached garage, a Cyclops visage in shingle and glass. She would be there in ten or fifteen minutes, and as she rode she was aware of the thick-lipped whistle of the breeze in the trees. She was wearing a pair of black bike shorts and a jersey with an image of a yellow tequila bottle that looked phosphorescent printed on the front. She didn’t feel especially vulnerable. She felt, if anything, lithe and athletic and strong. She was nineteen.

Then a brown van passed her. Not a minivan, a real van. The sort of van that, when harmless, is filled with plumbing and electrical supplies, and when not harmless is packed with the deviant accoutrements of serial rapists and violent killers. Its only windows were small portholes high above the rear tires, and she had noticed as it passed that the window on the passenger side had been curtained off with black fabric. When the van stopped with a sudden squeal forty yards ahead of her, she knew enough to be scared. How could she not? She had grown up on Long Island-once a dinosaur swampland at the edge of a towering range of mountains, now a giant sandbar in the shape of a salmon-the almost preternaturally strange petri dish that spawned Joel Rifkin (serial killer of seventeen women), Colin Ferguson (the LIRR slaughter), Cheryl Pierson (arranged to have her high school classmate murder her father), Richard Angelo (Good Samaritan Hospital’s Angel of Death), Robert Golub (mutilated a thirteen-year-old neighbor), George Wilson (shot Jay Gatsby as he floated aimlessly in his swimming pool), John Esposito (imprisoned a ten-year-old girl in his dungeon), and Ronald DeFeo (slaughtered his family in Amityville).

In truth, even if she hadn’t grown up in West Egg she would have known enough to be scared when the van stopped on the lonely road directly before her. Any young woman would have felt the hairs rise up on the back of her neck.

Unfortunately, the van had come to a stop so abruptly that she couldn’t turn around because the road was narrow and she used a clipless pedal system when she rode: This meant that she was linked by a metal cleat in the sole of each cycling shoe to her pedals. She would have needed to snap her feet free, stop, and put a toe down to pivot as she swiveled her bike 180 degrees. And before she could do any of that two men jumped out, one from the driver’s side and one from the passenger’s, and they both had those intimidating masks shielding their faces: a very bad sign indeed in late September, even in the faux tundra of northern Vermont.

Читать дальше