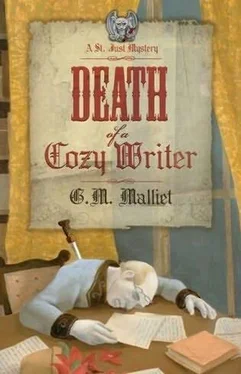

She gave a little shudder to demonstrate the horridness of it all, but in general, Albert thought, she was having a hard time concealing her rabid interest. Only natural, as well. Not only did the story have elements of irony-two members of a family whose name was synonymous with bloody murder being done in by foul play-but there was the added frisson of the opportunity for the press to drag Violet’s historic old crime-alleged crime-across the front pages yet again. And in Mrs. Butter’s case there was an added thrill: She knew two of the victims at first hand, and one of those quite well.

She seemed to be following his train of thought, as her next words revealed:

“Of course, knowing Sir Adrian as well as I did does make a difference.”

“Of course.”

She turned, stretching her hands toward the fire. After a long pause, she said musingly:

“Ruthven and Sir Adrian.” Albert noticed it was not the conventional “poor” Ruthven or “poor” Sir Adrian.

“Both,” she continued. “It’s very strange, that.”

“The whole thing is strange,” said Albert.

“No. No, what I meant was-and I hope I’m not being too indelicate, but-what I meant was, Ruthven’s death was a surprise, in a way. Sir Adrian’s was not. I can’t begin to tell you why I feel that way about it, but I do.”

Albert, who felt it was a case of six of one, half a dozen of the other, held his tongue.

“I used to blame you children. At first, you know. I hope you’ll forgive me. But I was astonished at the lack of family feeling. Few visits, fewer letters. I thought his isolation sad, inexplicable. Then later, of course, I came to understand.”

“You were there some time, weren’t you?”

“Five years, to the day.”

“Remarkable.”

“Yes, wasn’t it? I wanted to leave after three months. But Sir Adrian had promised me-in writing, thank heaven-quite a generous pension for which I would qualify after five years. With Mr. Butter gone-well, you won’t want to hear all of that. But I rather desperately needed that pension. Of course, he tried to renege on the agreement when I left-I knew he would. Which is why I had quite a vicious solicitor lined up before I gave notice. My nephew,” she added, smiling.

Albert laughed.

“You must be one of the few people who worked for my father who have a success story to tell.”

“I imagine. I survived by avoiding him as much as possible. As I came to realize all of you children did, as well.”

It was a sad but true commentary on the family dynamic, thought Albert.

She had resumed her study of the flames in the fireplace.

Into the pause, Albert said, “Why did you say earlier you were surprised? About Ruthven?”

She turned to him.

“Hmm? Oh, just because, it’s rather obvious, don’t you think? I can quite see why he might be killed by even a casual acquaintance- forgive me, I know I’m being blunt-but to kill him during a family gathering, when the suspicion would quite naturally fall on the family… It’s so risky, don’t you see?”

“You think a more public setting, something designed to look like an accident, perhaps…”

“Something like that, yes. Someone pushing him under the Bakerloo Line, perhaps. Something that would point the suspicion a bit away from the family, not right toward it. I must say, none of you children ever struck me as stupid-even George, if you will forgive me, has a certain animal cunning. You were all bright and talented, in your different ways, in spite of it all.”

Albert did not quite know what to say. On the one hand, she was complimenting him-all of them-on being too bright to commit murder, at least in an obvious way. “Thank you” didn’t quite meet the situation.

“Perhaps the manuscript will shed some light?”

“Oh, yes. That’s why you’re here, isn’t it? Dreadful things. I never needed reading glasses until I worked for your father. Part of the problem, of course, was that he could barely see what he wrote, having writ, so to speak. Let’s take a look.”

She pulled out of a knitting basket at her side a pair of thick spectacles on narrow gold frames and proceeded to attach them to her ears. She reached to accept the pages Albert had pulled from his rucksack.

“Good heavens,” she said, riffling through the pages. “Worse than ever. This will take awhile.”

“I am quite willing to pay for your time. I realize this is a huge imposition on you.”

She laughed, a little chirping sound that rippled through the room and (nearly) woke the cat.

“This is quite the most exciting thing to come my way in an age. You did say when you rang this was not, perhaps, his usual run of manuscript.”

Albert wondered how much he could take her into his confidence, but felt he had little choice.

“I really can only go by the title, but I think there’s bound to be something in there that sheds some light on… something. Something he knew. Perhaps the something that got him killed.”

But she barely noticed what he said. She had begun to read, slowly, tracing the manuscript line by line, occasionally pausing to hold a page closer to her lenses. He could hear a clock ticking in the background, punctuated by the sound of the village church bell tolling the quarter hour.

For a man whose minimum daily requirement of calories tended to come from alcohol, it was a shock to the system to have butter and sugar and flour coursing through his veins. His stomach seemed to have nearly forgotten the formula for converting these ingredients into energy. The unaccustomed exercise of the day-he was more used to spurts of manic activity on the stage than steady walks through the woods-acted, on top of the recent stress, the hot tea, and the fire, as a soporific.

At one point, a second Siamese wandered in, a missing bookend to the first, and settled itself on a pile of periodicals near the hearth before gazing off, cross-eyed, into space.

“There you are, Cly,” she said, looking up. “I wondered where you’d got to.”

“Sisters?” asked Albert, his mind elsewhere.

“Mother and daughter. Clytemnestra is slightly smaller than Leda. It’s the only way I can tell them apart.”

After awhile, Albert asked her permission to replenish the wood in the fireplace. Then he sat back down and watched the Roman Empire cat, it’s back rising and falling with sleep, and soon, inspired, began nodding off himself.

It was a long time before Mrs. Butter removed her glasses and looked up from her task. Albert, by this time, was sound asleep, gently snoring. She studied him awhile, remembering a younger Albert, before time and drink had left their handprints. She wondered very much what was best to do.

There are people in this world who, while they hold to a high and strict moral code, include in that code the necessity for lying once in awhile in the service of a greater cause. Mrs. Butter was of this flexible school.

Finally, she reached her decision. She cleared her throat. Then again, louder. Albert started awake.

“I don’t know how to tell you this, and or whether to tell you at all,” she said. She looked at him closely to be sure he was awake enough to take in what she said. His eyes were clear, focused. She realized with some surprise that she might never have seen him sober before.

“What is it?” he said. “You’re worrying me now.”

“I am sorry; I don’t mean to. We have to remember we don’t know, never will know, probably, if your father was writing fiction here, or fact. But if he’s done what I think…”

“Go on!”

“Were you aware, Albert, that Ruthven was only your half -brother?”

ST. JUST AND FEAR found Sarah in her rooms on the first floor, dealing cards from the bottom of a tarot deck.

Читать дальше

![Изабель Гиллис - Cozy. Искусство всегда и везде чувствовать себя уютно [litres]](/books/406910/izabel-gillis-cozy-iskusstvo-vsegda-i-vezde-chuvs-thumb.webp)