It took Watters a moment to realize he was being asked to leave.

“She had nothing to do with it, no more than I done,” he said.

“I just have a few questions. Mrs. Romano was in the house more often than you were.”

While that was patently untrue-from what he could tell, Watters spent most of his time hanging about the kitchen-the old man gathered his things and with a supportive little wave at Mrs. Romano, took his leave.

“He means well, Inspector. And it was a nasty trick to try to involve him, whoever did this. Watters wouldn’t hurt a fly.”

He had to agree, it was difficult to picture Watters worked up to a murderous fury. He sat down in Watters’ place across the table and regarded her.

“You’d worked for him a long time, Sir Adrian, hadn’t you?”

“I knew him for years. Decades. I never thought I would live to have such a shock, finding him like I did. Poor man, he did not deserve this. No one does. Ruthven, either. Whoever did this is wicked and cruel. I will not believe…”

She stopped, evidently fighting back tears, her mouth working.

“Not believe what, Mrs. Romano?” he asked gently, willing her to look up from the tea cup that held her enthralled.

She raised her fine eyes to look at him squarely.

“I’ll not believe any of them did this,” she said evenly. “It’s monstrous. Cold-blooded. And what did it gain them? He was an old man; he would have died soon enough, anyway.”

“Maybe someone just couldn’t wait.”

She nodded. Clearly she had been thinking along the same lines.

“Were you aware that both you and your son were mentioned in the will?”

“Paulo? Paulo, as well? No. No, I had no idea, no expectations. Not for either of us. That would have been wrong, to even think of it. Paulo had no idea either,” she added, staring at him unblinkingly, willing him to believe.

“Three hundred thousand pounds. Each.”

“ Buon Dio .” Her hand flew to her heart. “ No .”

“Not as much as was left to his family, of course.”

“Of course,” she said hastily. “Of course. Of course not. Three hundred thousand? Six hundred thousand for us? Are you sure?”

“He was a wealthy man, Sir Adrian.”

“Wealthy. Sì ,” she said. “In some ways. He had so much, but… Inspector, I have something to ask of you.”

“Go on.”

“I would ask you this: Do not tell Paulo about this money. Money like that, it can ruin a man, but especially-Let me be the one to tell him.”

Nodding, not even knowing why, St. Just saw no harm in agreeing.

As if making the decision as she spoke, she said slowly:

“I will return to my country. Sir Adrian, he must have known: That is what I most wanted. To be with my family, to live my old age where it is warm.”

She might have been speaking of her people or the weather. As he watched, the tears in her large almond-shaped eyes escaped. She made no attempt to wipe them away, crying as openly as a child.

She turned away toward the kitchen window. Outside was the iced-over garden, fallow until spring. Suddenly, everything around her seemed foreign; Sir Adrian had been the only anchor holding her here. She thought of her pre-Paulo days and traveled in her mind the long road back to where she had met her feckless young husband: he a handsome footman with big dreams, she a girl in service. It was he who had convinced her to move south to Cambridge, believing it would be warmer. Sciocco , she thought, fondly.

“God rest his soul,” she said.

St. Just assumed she was still speaking of Sir Adrian. It was the first time he’d heard him spoken of with affection.

***

He found Paulo nearby in the butler’s pantry, to which Mrs. Romano, now dabbing her eyes with a dish towel, had reluctantly directed him. The pantry lay just inside the brass-studded baize doors that led into the servants’ quarters. It was a large room that seemed to serve as both a supply area and Paulo’s personal sitting room, the furniture a mismatched jumble apparently accumulated at random over the years. Two plump armchairs in clashing plaids were drawn up close to the hearth. On a side table lay a stack of magazines, largely concerned with the opposing worlds of women and rugby.

Paulo was in mufti: artfully torn jeans and a Stanley Kowalski T-shirt. He gazed up out of doe’s eyes as beautiful and long-lashed as his mother’s. He struck St. Just as one of those men who had little use for other men and was fully aware of the effect he had on women (unlike St. Just, who was always taken aback). Still, he was friendly enough as he offered the policeman a drink.

“Whiskey, if you have it.”

“We have everything you could want in this house,” said Paulo.

“And more in the cellars besides?”

St. Just could almost hear Paulo’s brain whirring as he parsed the remark for hidden implications.

“Frightful, it was, what happened to Mr. Beauclerk-Fisk. To both of them.”

“Yes. About that cellar,” said St. Just, accepting the glass which Paulo now reluctantly handed him. “I’ve been wondering how a man in Sir Adrian’s condition could have managed those stairs.”

Paulo weighed loyalty to his former employer against the unwanted scrutiny of the Cambridgeshire Constabulary, with whom he wanted no repeat dealings. Common sense and a strong sense of self-preservation tipped the scales. No contest: After all, the old man was dead now. Dropping the accent he normally assumed for his role as butler, he continued in his more normal mode of speech, a match for his street clothes.

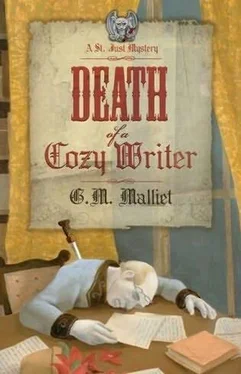

“He asked me to start hiding this book he was working on down the cellar, a bit at a time,” said Paulo, settling back in his chair. “It was the only place he could think to hide it where his snoopy family might not trip over it somehow.”

“When was the last time you were down there?”

“The day before Ruthven was killed. Honest. Look, I don’t want trouble; it’s not as if there was anything wrong in it. Sir Adrian, he’d give me the pages, a handful at a time, like I said. You’d think I was transporting diamonds, the way he carried on about it. ‘Don’t lose a page. One page missing, it’s the end of you,’ stuff like that.

Tell me to hide them down there, he would-add them to the stack already there, and be careful to keep them in order. The night Ruthven was killed, I started to go down very early in the morning, when I thought they would all be asleep, like. I hadn’t counted on Albert. There he was, in the middle of the bloody night, stumbling down the stairs. I guess headed to the cellar. Because not long after that, he started the holy hubbub about finding his brother.”

“We haven’t found any manuscript down there, and the room’s been sealed since the crime.”

“Well, then, I figure Sir Adrian, he hadn’t counted on that Albert. Said, ‘Albert won’t find it if you put it in with the beer; he always drinks up all the good stuff when he’s home.’ So smart, he’d cut himself, that was Sir Adrian. Thought he knew them all so well. He hadn’t counted on Ruthven, either. That one would move heaven and earth to know what the old man was up to.”

He leaned forward confidingly.

“I can tell you this. Them two were plotting. Or, more exact-like, Ruthven wanted Albert to go to Violet-threaten her-with what Ruthven had dug up on her. Albert wouldn’t have no part of it. They fought. I heard them-just happened to hear them.”

More likely, eavesdropped until he heard them. Still, St. Just didn’t care how he came by his information. Eavesdroppers were always useful.

“And what else?”

“That’s all I heard. Albert, he blew him up; said Ruthven could do his own dirty work or get his men to do it for him.”

Читать дальше

![Изабель Гиллис - Cozy. Искусство всегда и везде чувствовать себя уютно [litres]](/books/406910/izabel-gillis-cozy-iskusstvo-vsegda-i-vezde-chuvs-thumb.webp)