Perhaps, in some dark way, it was everything I had been waiting for; something that was sufficiently powerful to drive me away.

I stepped forward.

I looked down at her.

Even as I stared at her cold and lifeless face I could hear her voice.

Could hear the songs she sang to me as a baby.

I turned back towards my father, his back towards me, his body rigid and yet shaking uncontrollably, his fists clenched, every muscle inside of him taut and stretched and painful, and I knew that I had to leave. Had to leave and take him with me.

I ran from the house. The street was deserted. I ran back without any comprehension of why I had left.

I shouted something at him and he looked at me with the eyes of an old man. A weak and defeated man. I hurried to my room and gathered some clothes, stuffed them into a hessian sack; from the kitchen I took what few provisions remained, wrapped them in a cloth and buried those in the sack also, and then I took a shirt and forced my father’s arms through the sleeves, buttoned it to the neck, and then walked him out, walked him as if I was marching with two bodies, and I took him down to the side of the road and left him standing there, gaunt and speechless.

I returned to the house, and after standing over the dead form of my mother for a minute further, after kneeling and touching her face, after leaning close and whispering to her that I loved her, I backed up and returned to the kitchen. I took a kerosene lamp and emptied its contents in a wide arc across the floor and the table, trailed it out through the doorway and down the hall, and with the last inch and a half of fuel I doused my mother’s body. I backed up, I closed my eyes, and then took a box of matches from my pocket and lit one. I stood there for a moment, the smell of sulphur and kerosene and death in my nostrils, and then I dropped the match and ran.

We had run a quarter of a mile before I saw the flames make their way to the sky.

We kept on running, and ever-present was the urge to run back, to douse the flames and drag her charred body from the ruins, to tell the world what had happened, and ask a God I didn’t believe in for forgiveness and sanctuary. But I did not stop, nor did my father beside me, and in some strange way I believed that that was the closest I had ever been to him, the closest I would ever come.

It was December of 1958, a week before Christmas, and we headed east towards the Mississippi state line, and when we reached it we headed still east towards Alabama, knowing full well that to stop was to see our destiny slip from our hands.

Seventeen days we walked, stopping only to lie at the edge of some field and snatch a broken handful of hours’ rest, to share the few mouthfuls of food that remained, to rise and ache through yet another day of passage.

Into Florida: Pensacola, Cape San Bias, Apalachee Bay; into Florida, where you could see the island of Cuba, the Keys, the Straits and the lights of Havana from the tip of Cape Sable. And knowing that we were merely a handful of miles from my father’s homeland.

We hid for three days straight. My father said nothing. Each day I would creep away at night and walk down to the beaches. I talked with people who spoke in broken-up Spanish, people who told me they could not help me time and time again, until finally, on the third night, I found a fisherman who would take us.

I will not tell you how I traded for our passage, but I closed my eyes and I paid the price, and I still believe that I carry the scars of my own fingernails in the flesh of my palms.

But we were away, the wind in our hair, the sea air like some cleansing absolution for the past, and I watched my father as he clung to the edge of the small craft, his eyes wide, his face haunted, his spirit broken.

That was my mother.

Her life and her death.

I was twenty-one years old, and in some way I believed my own life had come to an end. A chapter had closed with a sense of finality, and if ever I believed I could recover from what had happened, if ever I believed that there was some way back from the events of my childhood, from not only the murder that I had now committed, but also the murder I had witnessed, then I was mistaken.

My soul was lost; my destiny was closed and sealed and irreversibly decided; the world and all its madness had challenged me and I had succumbed.

If ever there was a Devil, I had accepted him as my bedfellow, my compadre, my blood-brother, my friend.

I had at first followed in my father’s footsteps, and then rescued him from justice for the killing of my mother.

In my mind was a darkness, and through my eyes I saw that same darkness everywhere I looked.

What was once within now became all that was without.

We landed at Cardenas. I brought with me a shadow that I carry to this day.

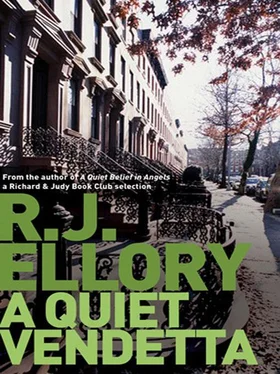

Of all the things he had learned, Ray Hartmann knew one thing for certain: that it was not possible to apply reason to an unreasonable action.

Perhaps in some dark and shadowed corner of his mind he could find some measure of understanding for these things that had been done – the killing of Perez’s mother, the burning of the body, the escape to Cardenas in Cuba, even the death of the salesman – but he could not begin to understand the man who had done them. Hartmann did not believe evil was hereditary, but just as he had studied before, just as he had learned in books by Stone and Deluca, the O’Haras and Geberth, he believed there were indeed situational dynamics . This was the territory of criminal profiling, and here he was, lost and without anchor, hurled headlong into something that he could never believe real.

‘You are somewhat introspective, Mr Hartmann,’ Perez said quietly, and leaning forward he took a cigarette from the packet on the table and lit it.

‘Introspective?’ Hartmann echoed.

Perez smiled. He drew on his cigarette and then issued two fine streams of smoke from his nostrils.

Like a dragon , Hartmann thought. A dragon with no soul .

Perez shook his head. ‘You find such things difficult to comprehend?’

‘Yes, perhaps,’ Hartmann replied. ‘I have read thousands of pages, seen hundreds and hundreds of pictures of such things, the things men can do, but I don’t know that I am any the wiser as to motive and rationale.’

‘Survival,’ Perez stated matter-of-factly. ‘It always comes down to nothing more fundamental than survival.’

Hartmann shook his head. ‘That’s something I can’t agree with.’

‘I see,’ Perez replied. ‘I see.’

Hartmann leaned forward. ‘You truly believe that all the things that have been done have been in the name of survival?’

‘I do.’

‘How so? How could survival ever justify murder?’

‘That is easy, Mr Hartmann, because more often than not it is simply a matter of yourself or them. Faced with such a situation there are few that would be willing to sacrifice their own lives.’

Hartmann looked at Perez, looked right at him, and believed that this man was more animal than human being. ‘But what about paid killers… what about people who murder complete strangers simply for money?’

‘Or for knowledge?’ Perez asked, perhaps making reference to the death of Carryl Chevron.

‘Or for knowledge, yes.’

‘Knowledge is survival. Money is survival. The truth is that motive can never be truly appreciated by another. Motive is a personal thing, perhaps as personal and individual as the killer himself. He kills for some reason understood only by himself, and that reason can always be explained by the individual’s own perception of what will enable him to survive in the best manner at the time. Later, perhaps, in hindsight, a different viewpoint will lend itself to the situation and the perpetrator may believe that he has done wrong, but in the moment of the killing I can guarantee that it was adjudicated to be the most contributive to his own survival, or the survival of that which owned his loyalty.’

Читать дальше

![Quiet Billie - Don't mistake the enemy [СИ]](/books/421973/quiet-billie-don-t-mistake-the-enemy-si-thumb.webp)