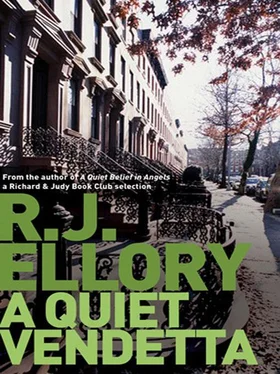

I turned and looked at them. I wondered if this was merely a coincidence, or if they were speaking of the same Ducane I had met so many years before.

I glanced towards them, and there, held up in the man’s hand, was the front page of a newspaper. The face of Charles Ducane – so much older, but so unmistakably the same man – looked back at me. And the headline over it, DUCANE LANDSLIDES GOVERNORSHIP, almost took my breath away.

I did not eat anything more, but called for the check, paid for my meal, and left the restaurant. I walked half a block and bought a newspaper from a street vendor, and there, in startling black and white, the same face smiled back at me from the front page. Charles Ducane, the very same man who had stood beside Antoine Feraud nearly forty years before; the same man who had orchestrated the killing of three people whom I had murdered through his indirect command, was now governor of Louisiana. I smiled at the dark irony of the situation, but at the same time there was something about this that unsettled me greatly. I had not liked Ducane, there had been something truly sinister and unnerving in his manner, and I could only imagine that he must have risen to such a credible position through the sheer quantity of money that was behind him.

I walked the streets, unable to identify what it was that disturbed me so about this man: his manner, his conceited attitude, the feeling that here was someone who had engineered his way through life and arrived at a governorship through Machiavellian deceit and murder? And he had been the one, alongside Feraud, who had attributed killings to my name. The thing about someone having their heart removed: that had been Ducane and Feraud. It angered me that I was now in hiding somewhere on the outskirts of New Orleans, unable to engage in life the way I wished, and yet this man – guilty of the same deeds – was now proudly smiling from the front page of a newspaper with his public reputation intact.

At some point I tore the newspaper in half and hurled it to the sidewalk. I went home. I sat in the kitchen and considered my reactions, but I decided that I could do nothing. What was there to do? It would not have served any purpose to expose the man. In order to do that I would have to lay bare my own soul, and what would that have accomplished? Ducane was the governor. I was an immigrant Mafia hood from Cuba, responsible for the deaths of countless men. I thought of my son and the shame it would bring upon him. Whatever happiness he had now discovered here in America would be obliterated by one single action. I could never do such a thing.

After a while I calmed down. I had a drink and felt my nerves settle. True, I was here in this small house living my quiet life, but nevertheless afraid of nothing. Ducane, however, was up there in his governor’s mansion, living with the ever-present possibility that someone might take an unhealthy degree of interest in his past. There would always be enemies, always be people who would find no greater pleasure than exposing the sordid details of some political figurehead’s past, and money – no matter how much he might have – would only keep such things away for so long. Someone else, I concluded, could bring Charles Ducane down, and that someone would not be me.

Nevertheless I took an interest in the man. I watched him when he came on the TV. I went to the New Orleans City Library and learned something of his route to the governorship. He had been involved in state and city politics his entire adult life. He had worked alongside and within the bureaux that handled land acquisitions and property rights mergers, civil litigation, state legislature and union affiliations for industry and manufacturing plants. At one time he had spent six months as legal advisor to the New Orleans State Drug Enforcement Agency under the auspices of the FBI. The man had been busy. He had used his money and influence to carve out a position for himself within the political ranks of Louisiana, and for his efforts, for his undoubted generous contributions to many important funds and campaigns, he had been rewarded with his current title. In some ways he was a man not unlike me; he had used what he possessed to make something of his life, but whereas I had come from nowhere and ended up nowhere, he had started somewhere and wound up in an even more elevated position.

I collected newspaper articles about Ducane. I made an effort to see him when he made public appearances, and though there was even a moment when I approached him at the opening of a new art gallery and shook his hand enthusiastically, there was no indication of recognition. I knew who he was, I knew where he had come from and what he had done, but of me he knew nothing. I had been a means to an end forty years before, and beyond that he had even used my name to cloud the facts regarding several killings that had taken place. Whereas he was in the public eye, I remained anonymous, and that fact in itself became a source of particular enjoyment for me.

The following year Emilie returned once again for the Mardi Gras. The first week of April, and the streets of New Orleans exploded with life and color and sound. Once again her Uncle David brought her down, and once again he managed to be there without ever really being there at all. He was a strange man, quiet and aloof, and yet he seemed to have no difficulty permitting Emilie to spend much of her vacation with us. I believed that Emilie was more than a little responsible for his lack of opposition. We had seen her briefly a little before Christmas, but it had been a year since the previous Mardi Gras, and within that year she had grown. Victor would be nineteen in a couple of months, and in the following September Emilie would reach eighteen. She was a young woman, spirited and independent, and though I recognized her passion for life and all it offered, there was nevertheless an element of her character that I felt sprang from the strained relationship she seemed to have with her father. While she was with us she never called him, and he – apparently – never made any attempt to contact her. I questioned her one time, carefully, diplomatically, and her responses were dry and monosyllabic.

‘He runs his own business then, your father?’

‘And tries to run everyone else’s as well,’ she replied, in her eyes an expression of sour disapproval.

‘He is a driven man, it seems.’

‘By money, yes. By anything else, no.’

I was quiet for a time. I watched her. She seemed at her most unhappy when the conversation turned towards her own family.

‘But he cares a great deal for you, I am sure, Emilie.’

She shrugged.

‘He is your father, and despite the fact that he is a busy man I am sure that he loves you a great deal.’

‘Who the hell knows?’ Again the sour expression, the flash of irritation in her eyes.

‘All fathers love their children,’ I said.

She looked at me. ‘Is that so?’

I nodded. ‘Yes it is, and though there might be some people who find it difficult to express the way they feel it doesn’t change the fact that they still feel those things towards their own blood.’

‘Well, maybe my father is the exception that proves the rule, eh?’

I shook my head. She was stonewalling me. ‘And your mother?’

Emilie smiled bitterly. ‘She left him, couldn’t take any more.’

‘And where is she now?’

‘Around and about.’

‘You see her?’

‘Every so often.’

‘And she is perhaps a little more forthcoming in her affections for you?’

‘She’s as crazy as he is, but in a different way. She spends all her time worrying about what other people might think of her. She’s possibly the most introspected and self-centered person I know.’

I smiled. ‘Then tell me one thing?’

Читать дальше

![Quiet Billie - Don't mistake the enemy [СИ]](/books/421973/quiet-billie-don-t-mistake-the-enemy-si-thumb.webp)