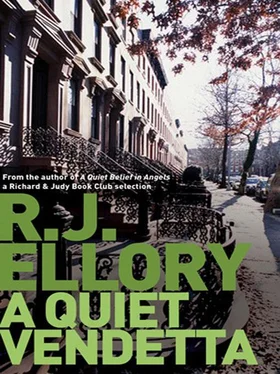

It was the same for Angelina and Lucia. Someone somewhere had ordered Don Calligaris’s death, a bomb had been placed in his car, Don Calligaris had survived without a scratch. Someone somewhere would make a phone call to someone somewhere else, the differences would have been resolved in a handful of minutes, and the matter would have been closed. End of story. Evidently whoever had ordered the hit no longer wanted Don Calligaris dead or they would have tried again, and they would have kept on trying no matter how many attempts it took, and no matter who might have gotten in the way. Angelina and Lucia, well, they had gotten in the way, and had I been blood, had we been a part of this family for real, then perhaps someone might have done something. But I was Cuban, and Angelina had been the unwanted product of an unwanted embarrassment to the family, and it was not necessary for anyone to balance the scales in my favor. My connection to Don Calligaris had been enough to put my family in the line of fire, and though I bore no grudge against him, though I understood that he could do nothing directly to help me, I also knew that someone somewhere was responsible, and someone should pay.

That thought stayed with me until I slept, but when I woke it had left my mind. I did not forget, I merely changed its order of priority. It was there, it would never disappear, and there would come a time to do something about it.

The summer of 1999, and Victor’s seventeenth birthday in June. It was then that I met the first girl he brought home. She was an Italian girl, a fellow student from his school, and in her deep brown eyes I saw both the innocence of youth and the blossoming of adulthood. Her name was Elizabetta Pertini, though Victor called her Liza and this was the name by which she was known. In some small way she was not unlike Victor’s mother, and when she laughed, as she often did, there was a way she would raise her hand and half-cover her mouth that was enchanting. She wore her raven hair long, often tied at the back with a ribbon, and I knew within a matter of weeks, good Catholic girl or not, that she was the one who took my son and showed him that which had been shown to me by Ruben Cienfuegos’s cousin Sabina. He changed after that, as all young men do, and he became independent to an extent I had not seen before. Sometimes he was gone for two or three days, merely calling to let me know that he was fine, that he was with friends, that he would be back before the week was out. I did not complain, his grades were good, he studied well, and it seemed that Liza had carried something into his life that had been altogether missing. My son was no longer lonely. For this alone I would have been eternally grateful to Elizabetta Pertini.

The discussion that took place between her father and myself in the spring of the following year did not go well. Apparently Mr Pertini, a well-known bakery owner from SoHo, had discovered that his daughter, believed to be visiting with girlfriends, perhaps studying for her school examinations, had been spending time with Victor. This subterfuge, orchestrated no doubt by Victor, had continued for the better part of eight months, and though I was tempted to ask Mr Pertini how he had managed to be so utterly unobservant of his daughter’s comings and going, I held my tongue. Mr Pertini was irate and inconsolable. Apparently, and this unknown to his daughter, he intended her to marry the son of a family friend, a young man called Albert de Mita who was – even as we spoke – studying to be an architect.

I listened patiently to what Mr Pertini had to say. I sat in the front room of my own house on Baxter where he had come to find me, and I heard every word that came from his lips. He was a blind man, a man of ignorance and greed, and it wasn’t long before I discovered that his business had been struggling financially for many years, that the intended marriage of his daughter into the de Mita family would reap a financial benefit sufficient to rescue him from potential ruin. He was more interested in his own social status than the happiness of his daughter, and for this I could not forgive him.

But there was a difficulty with whatever challenge I might have raised to his objections regarding my son courting his daughter. Pertini was a man of repute. He was not a gangster, he was not part of this New York family, and thus any issue of loyalty to Don Calligaris would carry no weight. Thirty years ago he would have been visited by Ten Cent and Michael Luciano perhaps. They would have shared a glass of wine with him and explained that he was interfering in the business of the heart, and sufficient funds to compensate for the loss of his daughter’s ‘dowry’ would have been delivered in a discreet brown package to one of his bakeries. But now, here in the latter part of the twentieth century, such matters could no longer be resolved in the old way. Any suggestion I might have made to Pertini about money would have been taken as offensive. No matter his thought or intention, no matter the fact that he knew I understood his motives, on the face of it he would have been insulted. That would have been his part to play, and he would have played it to the hilt. He professed an appreciation of his daughter’s best interests. He knew as little of those as he did of my business. But had I insisted that there was a change in his plan, had I attempted to persuade him to reconsider who his daughter might marry, then Pertini – I felt sure – would have done all he could to raise questions about my reputation and credibility. That route would have been the route to his death for certain, and however much I loved Victor, however much I might have cared for his happiness and the welfare of his heart, I also felt that I could play no part in depriving Liza of her father.

The relationship was ended abruptly in April 2000. Victor, not yet eighteen, was inconsolable. For days he did not venture from his room further than the bathroom and the kitchen, and even then it was to eat next to nothing.

‘But why?’ he asked me incessantly, and no matter how many times I tried to explain that such things were often more a matter of politics than love, there was nothing I could do to make him understand. He did not blame me, merely resented my apparent lack of effort in preventing what had happened. Liza was grounded at home for those weeks, and on one occasion when Victor attempted to call her the attempt was cut short within seconds by her father. Moments later Mr Pertini called me at the house and told me in no uncertain terms that I was responsible for my son, that if I did not ensure there were no further attempts to contact his daughter then he would seek an injunction against him for harassment. I assured him that no further attempt would be made. To me it was obvious why such a thing had to be prevented, but there was no way I could explain that to Victor. Again he saw me as failing to defend what he considered to be his God-given right.

It was not the only issue that contributed to my position in New York becoming untenable, but it perhaps marked a watershed. The matter that finally prompted our departure was far more serious indeed, at least for me, if not for Victor, though had we stayed there would have been questions asked that could never have been answered. The events of the latter part of March and the first week of April that year were perhaps indicative of how single-minded and relentless I had become in attempting to find some meaning for my own life. Back of all of it was the ghost of my wife, that of my daughter also, and though they were never far from my thoughts, it was in my actions that I recognized how unfeeling and brutal I would become if I did not assuage my sense of guilt about their deaths. That guilt could only be tempered by revenge, I knew that as well as I knew my own name, and it was in those weeks that my feelings of merciless rage were precisely demonstrated.

Читать дальше

![Quiet Billie - Don't mistake the enemy [СИ]](/books/421973/quiet-billie-don-t-mistake-the-enemy-si-thumb.webp)