Ahmad, Garcia and I would sleep in shifts, with two guards always awake and on duty. The shepherd’s bedroom was a small one on the ground floor, between the front door and the bedrooms for the principals.

I knew the layout of the compound and the safe house perfectly and Ahmad, who’d never been here, had studied the place. I’d tested him several times-most recently a month ago-and I knew that he was familiar with the layout. I had him brief Garcia and I explained to the FBI agent about the com system and the weapons locker. I gave him the combination to the lock. Inside there wasn’t much; some H &Ks and M4 Bushmasters, tripped to fully auto, sidearms and flash-bang grenades, like the sort that we’d used against Loving at the flytrap.

With my principals now safely inside their fortress, I walked into the den, which I used as my office, sat at the ancient oak desk and booted up my laptop. I plugged it and my phone into the wall socket; in the personal security business there are many important rules, Abe had recited, but high on the list: “Never miss a chance to recharge batteries or use the bathroom.”

I’d done the former; I now did the latter, walking into the front bedroom. I washed my hands and face in the hottest water I could stand and checked the scrapes and bruises from the pursuit of Loving at the flytrap. Nothing serious, though my back ached like hell from the jarring escape in the Yukon at the Hillside Inn.

I walked through the house, checking sensors and making sure all the software and com systems were working. I felt like an engineer.

Personal security is a state-of-the-art profession; it has to be, since the bad guys know all the toys… and have seemingly unlimited budgets to buy them. Although, as you’d think with somebody who prefers board to computer games, I’m not inherently high tech, I nonetheless made sure we too had the latest gadgets: explosives sniffers as small as a computer mouse, which they resemble; high-density carbon-fiber detectors for nonmetallic firearms, audio sensors that can alert us to the sounds of an automatic weapon slide slamming a round into the chamber, or the click of a revolver cocking; microphones that will reassemble conversations from vibrations on the other side of the wall; communications jammers; GPS signal reorienters that will send the car following you right off the road.

I always carried in my breast or hip pocket a video camera disguised as a pen. It was linked to software whose algorithms alerted me that the body language of a person approaching was consistent with that of an impending attack. I also used it to record crowds in public when I was transporting principals, to see if faces of passersby in one locale turn up in another.

A second “pen” is actually a wireless signal detector to sweep for bugs.

There was even what we call a “mail box”; it’s about a foot square and unfolded explosively outward when it heard a detonation of an IED, shooting a Kevlar and metal mesh-like knight’s chain mail-upward, to intercept as much shrapnel and blast force as possible.

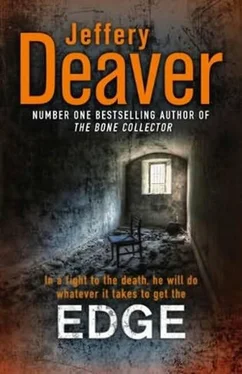

Sometimes these devices worked and sometimes they didn’t. But you do whatever you can to get an edge over your opponent, Abe Fallow used to say. That edge could be microscopic, but often that was enough.

I returned to my computer and downloaded several emails that duBois had sent. I was sending replies when I sensed a presence. I looked up and saw the Kesslers in the kitchen. I heard cabinets opening, the refrigerator door. This facility does have a bar, which separated the dining room and kitchen, but it’s stocked only with sodas. In the kitchen our facilities person usually has some wine and beer. Although we can’t drink on duty, of course, we try to keep our principals as comfortable as possible-and more important, try to give them little to complain about.

Ryan limped to the bar and poured some Coke into a glass that was already half full of amber liquid. Joanne got a Sierra Mist. “You want something in it?” I heard him ask.

She shook her head.

His shrug said, Suit yourself .

He glanced into the den and saw me looking at them. He turned and walked back to the bedroom.

I returned to my computer, reviewing the encrypted e-files duBois had sent me.

She was responding to several of my various requests that day and assured me that she expected to have more details about Ryan’s two relevant cases. There was some more research I needed to do-by myself. I logged into a secure search engine we use-routing my requests through a proxy in Asia.

The information came back instantly; I wasn’t looking for classified material but simply perusing the general media. For a half hour I read through hundreds of pages of news stories and op ed pieces mostly. Finally I had a portrait of the object of my search.

Senator Lionel Stevenson was a two-term senator, a Republican from Ohio. He’d been in Congress before that and a prosecutor in Cleveland before running for office. He was a moderate, and respected on both sides of the aisle, as well as in the White House. Judiciary Committee for four years, now Intelligence. He was the one who’d hammered together a coalition to get just enough votes in the Senate for the Supreme Court nominee. One politician was quoted as saying of Stevenson’s efforts, “That was tough work, building support-everybody seems to hate everybody else in Washington nowadays.”

Too much screaming in Congress. Too much screaming everywhere .

He made visits to Veterans Administration hospitals and schools back in Ohio and in and around D.C. He was part of the Washington social scene and was seen in the company of younger women-though, unlike some of his colleagues, that was not a problem, since he was unmarried. He was supported by political action committees, lobbyists and campaign fund-raising organizations that had never run afoul of the law. He was considered one of the icons in what was being called the New Republican movement, which because of its moderate stance was converting Democrats and independents and looked likely to win solid majorities in upcoming state and federal elections.

Maybe the most significant thing I found were his remarks delivered at a community college in Northern Virginia a few months ago. While in many ways a fervent law-and-order advocate, Stevenson nonetheless said, “Government is not above the law. It is not above the people. It is bound by the law and it serves the people. There are those in Washington-there are those in every state-who think that rules can be bent or broken in the name of security and attaining a greater good. But there is no greater good than the rule of law. And politicians, prosecutors and police who would turn a blind eye toward the will of our Founders are no better than common bank robbers or murderers.”

The reporter stated that these remarks earned Stevenson a standing ovation from the hall full of future voters. Other articles observed that this philosophy had cost him votes at home from Republicans and occasional enmity from fellow GOPers in Congress. Which told me that his motive for the upcoming hearings on government surveillance was rooted in ideology, not winning votes.

I continued to scroll through the voluminous material, jotting a note or two.

I felt at sea doing this, and again I envied Claire duBois her research skills. This, however, was not an assignment I would give to her.

I glanced up to see Joanne stepping into the doorway between the kitchen and living room, leaning against the jamb, her stern handsome face a bit less numb than before. I saved the pages in an encrypted file and typed a command to bring up the password-protected screensaver.

I stared at the monitor for a moment, the images of chess pieces appearing and dissolving, as I reflected on what I’d just learned about Stevenson. Then I rose and walked to the doorway, nodding to Joanne.

Читать дальше