Months before, Joe had been assigned to the remote Baggs District in extreme south-central Wyoming. The district (known within the department as either “The Place Where Game Wardens Are Sent to Die” or “Warden Graveyard”) was hard against the Colorado border and encompassed the Sierra Madre Mountains, the Little Snake River Valley, dozens of third- and fourth-generation ranches surrounded by a bustling coal-bed methane boom and an influx of energy workers, and long distances to just about anywhere. The nearest town with more than 500 people was Craig, Colorado, thirty-six miles to the south. The governor had his reasons for making the assignment: to hide him away until the heat and publicity of the events from the previous fall died down. Joe understood Governor Rulon’s thinking. After all, even though he’d solved the rash of murders involving hunters across the state of Wyoming, he’d also permitted the unauthorized release of a federal prisoner-Nate Romanowski-as well as committing a shameful act that haunted him still.

Joe had called a few times and sent several e-mails to the governor asking when he could go back to Saddlestring. There had been no response. While Joe felt abandoned, he felt bad that his actions had damaged the governor.

And the governor had enough problems of his own these days to concern himself with Joe’s plight. Although he was still the most popular politician in the state despite his mercurial nature and eccentricity, there had been a rumor of scandal about a relationship with Stella Ennis, the governor’s chief of staff. The governor denied the rumors angrily and Stella resigned, but it had been a second chink in his armor, and Rulon’s enemies-he had them on both sides of the aisle-saw an opening and moved in like wolves on a hamstrung bull moose. Soon, there were innuendos about his fast-and-loose use of state employees, including Joe, even financial questions about the pistol shooting range Rulon had installed behind the governor’s mansion to settle political disputes. Joe had no doubt-knowing the governor-that Rulon would emerge victorious. But in the meanwhile, he’d be embattled and distracted.

And Joe would be in exile of sorts. He felt the familiar pang of moral guilt that had visited him more and more the last few years for some of the decisions he’d made and some of the things he’d done that had landed him here. Although he wasn’t sure he wouldn’t have made the same decisions if he had the opportunity to make them again, the fact was he’d committed acts he was deeply ashamed of and would always be ashamed of. The last moments of J. W. Keeley and Randy Pope, when he’d acted against his nature and concluded that given the situations, the ends justified the means, would forever be with him. Joe’s friend Nate Romanowski, the fugitive falconer, had always maintained that often there was a difference between justice and the law, and Joe had always disagreed with the sentiment. He still did. But he’d crossed lines he never thought he’d cross, and he vowed not to do it again. Although he owned the transgressions he’d committed and they would never go away, he’d resolved that the only way to mitigate them was to stay on the straight and narrow, do good works, and not let his dark impulses assert themselves again.

Being in exile could either push a man over the precipice or help a man sort things out, he’d concluded.

DESPITE THE REMOTE LOCATION, his lack of familiarity with the new district, and pangs of loneliness, the assignment reminded him how much he loved being a game warden again, really being a game warden. It was what he was born to do. It’s what gave him joy, purpose, and a connection to the earth, the sky, God, and his environment. It made him whole. But he wished he could resume his career without the dark cloud that had followed him once the governor had chosen to make him his go-to guy. He wished he could return home every night to Marybeth, Sheridan, and Lucy, who’d remained in Saddlestring because of Marybeth’s business and the home they owned. Every day, he checked his e-mail and phone messages for word from the governor’s office in Cheyenne that he could return. So far, it hadn’t come.

Life and work in his new district was isolated, slow, and incredibly dull.

Until the Mad Archer arrived, anyway.

By Joe’s count, the Mad Archer had killed four elk (two cows and two bulls whose antlers had been hacked off) and wounded three others he had to put down. He could only guess at the additional wounded who’d escaped into the timber and suffered and died alone. It was the same with the two deer and several pronghorn antelope off the highway between the towns of Dixon and Savery, all killed by arrows.

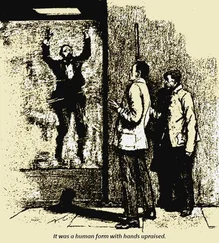

Then there was the dog-a goofy Lab-corgi hybrid with a Lab body and a Lab I love everybody please throw me a stick disposition tacked on to the haughty arrogance of a corgi and a corgi’s four-inch stunted legs-who’d suddenly appeared on the doorstep of Joe’s game warden home. He fed him and let him sleep in the mudroom while he asked around town about his owner. Joe’s conclusion was he’d been dumped by a passing tourist or an energy worker who moved on to a new job. So when the dog was shot through the neck with an arrow outside an ancient cement-block bar once frequented by Butch Cassidy himself, Joe was enraged and convinced the Mad Archer was not only a local but a sick man who should be put down himself if he ever caught him.

The dog-Joe named him “Tube”-was recovering at home after undergoing $3,500 worth of surgery. The money was their savings for a family vacation. Would the state reimburse him if he made the argument that Tube was evidence? He doubted it. What he didn’t doubt was that Sheridan and Lucy would grow as attached to the dog as he had. All Tube had going for him was his personality, Joe thought. He was good for nothing else. Was Tube worth the family vacation? That was a question he couldn’t answer.

Of course, the best Joe could do within his powers if he caught the Mad Archer would be to charge him with multiple counts of wanton destruction-with fines up to $10,000 for each count-and possibly get the poacher’s vehicle and weapons confiscated. Joe was always frustrated at how little he could legally do to game violators. There was some compensation in the fact that citizens in Wyoming and the mountain west were generally as enraged as he was at indiscriminate cruelty against animals. If he caught the man and proved his guilt before a judge, he knew the citizens of Baggs would shun the man and turn him into a pariah, maybe even run him out of the state for good. Still, he’d rather send the criminal to prison.

For the past month, Joe had poured his time and effort into catching the Mad Archer. He’d perched all night near hay meadows popular as elk and deer feeding spots. He’d haunted sporting goods shops asking about purchases of arrows and gone to gas stations asking about suspicious drivers who might have had bows in their pickups in the middle of summer. He’d acquired enough physical evidence to nail the Archer if he could ever catch him in the vicinity of a crime. There were the particular brand of arrows-Beman ICS Hunters tipped with Magnus 2-blade broadheads-partial fingerprints from the shaft of the arrows removed from an elk and Tube, a tire-track impression he’d cast in plaster at the scene of a deer killing, a sample of radiator fluid he’d gathered from a spill on the side of the road near the dead pronghorn, and some transmission fluid of particular viscosity he’d sent to the lab to determine any unique qualities. But he had no real leads on the Mad Archer himself, or even an anonymous tip with a name attached called into the 800-number poacher hotline.

Many of his nightly conversations with Marybeth took place in the dark in the cab of his pickup, overseeing a moon-splashed hay meadow framed by the dark mountain horizon.

Читать дальше